But this net-negative ‘title’ for Tassie hides a deeper issue. Yes, we are

net negative, but our

absolute emissions (the emissions we produce before accounting for forest removals) have barely changed in 30 years.

If this is not enough to motivate us to do better, 2025 is actually shaping up to be a great time for cutting emissions. In July, Tasmanians will head to the polls for another election with a chance to weigh candidates’ positions on climate and clean energy – and vote accordingly. There will also be another important opportunity for public input: The

2024-25 Independent Review of the Climate Change (State Action) Act 2008, soon open for public submissions, will assess how our climate action performance is measuring up to the requirements of the Act and whether more action is needed.

In this edition of PIMBY, we take you through the latest climate emissions data, cut through the net-zero noise to show what’s actually changing and what isn’t, and provide some options for what we can do right now to turn things around.

Understanding emissions and the data

Before jumping into the data and what it all means, it’s worth clarifying a few things.

First, “net zero” is when a jurisdiction’s emissions are equal to, or fewer, than the emissions removed and stored in forests and soils. “Net emissions” refer to the total greenhouse gases (known as carbon-equivalent orCO2-e emissions) emitted by a state or country, minus the amount removed from the atmosphere. “Absolute emissions” are the raw total of greenhouse gases released, not including removals. While net emissions give a good indication of our overall impact on the climate, absolute emissions provide a clearer picture of the activities actually generating carbon pollution.

So, Tasmania’s net emissions are negative because our forests remove and store more carbon than we emit. But this doesn’t mean we’re reducing the amount of emissions produced from our vehicles, farms, industries, or energy use.

For clarity, the STGGI breaks down emissions into five sectors, although we separate transport out from stationary energy as it makes it easier to understand:

In the STGGI data, our greenhouse gas emissions, are calculated using guidelines set by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The UNFCCC’s guidelines ensure consistent reporting across countries and jurisdictions while allowing flexibility to reflect local conditions.

This emissions-tracking system is enormously valuable for charting progress and comparing jurisdictions, but it isn’t flawless. When adjustments are made to the methodology or when new information becomes available, previous years’ data are revised – sometimes significantly. For example, Tassie’s first net-zero year was originally recorded as 2013, revised to 2014 in 2020, then back to2013 again in the following year.

Given that adjustments can easily mean the difference between meeting legislated emissions reduction targets and falling short of them, it is important to treat the resulting data cautiously. The problem is that most sectors, like transport and energy, are calculated using straight forward methods. For example, we can estimate transport sector emissions from cars accurately by multiplying fuel consumption by an indicator of how emissions intensive our fleet of passenger vehicles is (known as an ‘emissions factor’). Emissions and removals from LULUCF, however, are much more complicated. Modelling the volume of carbon removed and stored in trees is extremely complex and is done using a completely different method to other sectors. As a result, Tassie’s claim to net-zero emissions relies heavily on estimates that are inherently more uncertain than those in other sectors.

So this year’s update means we find out about our performance in 2023 (because there is a two-year delay in the data), if we are still net zero, and whether or not we managed to reduce our absolute emissions.

The latest emissions update

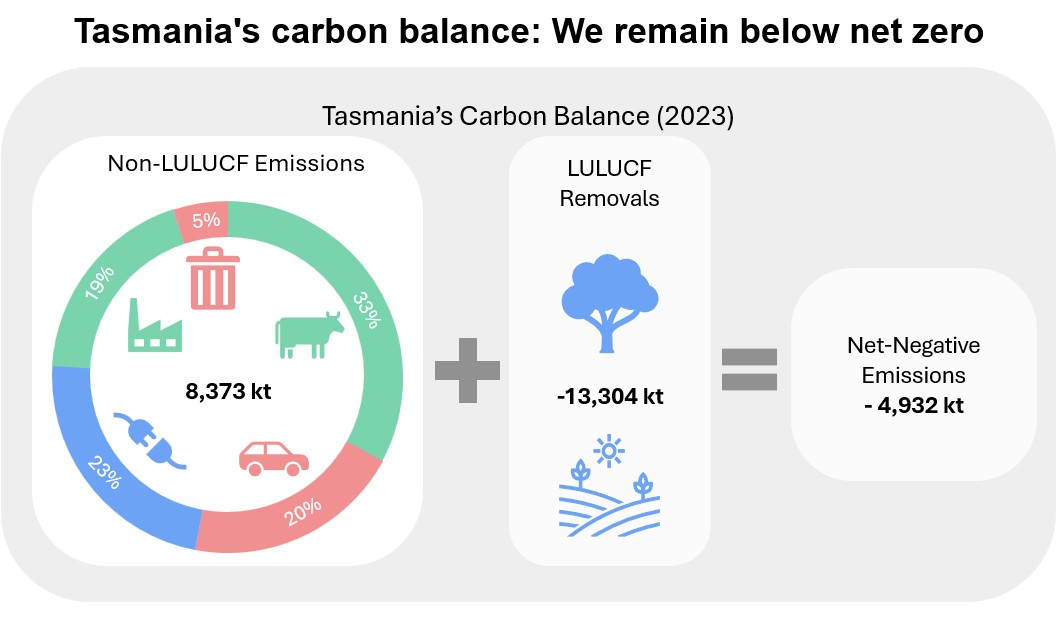

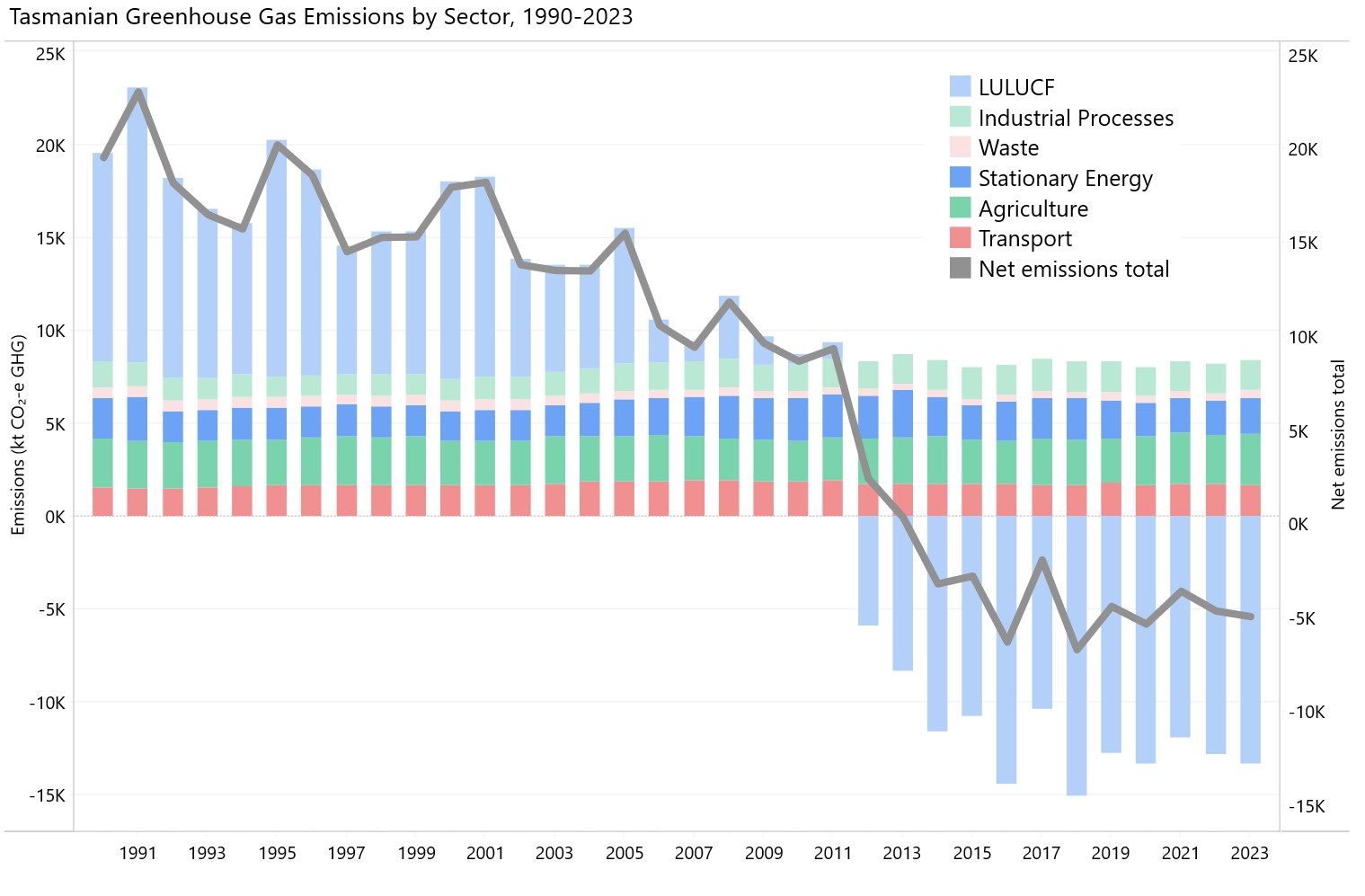

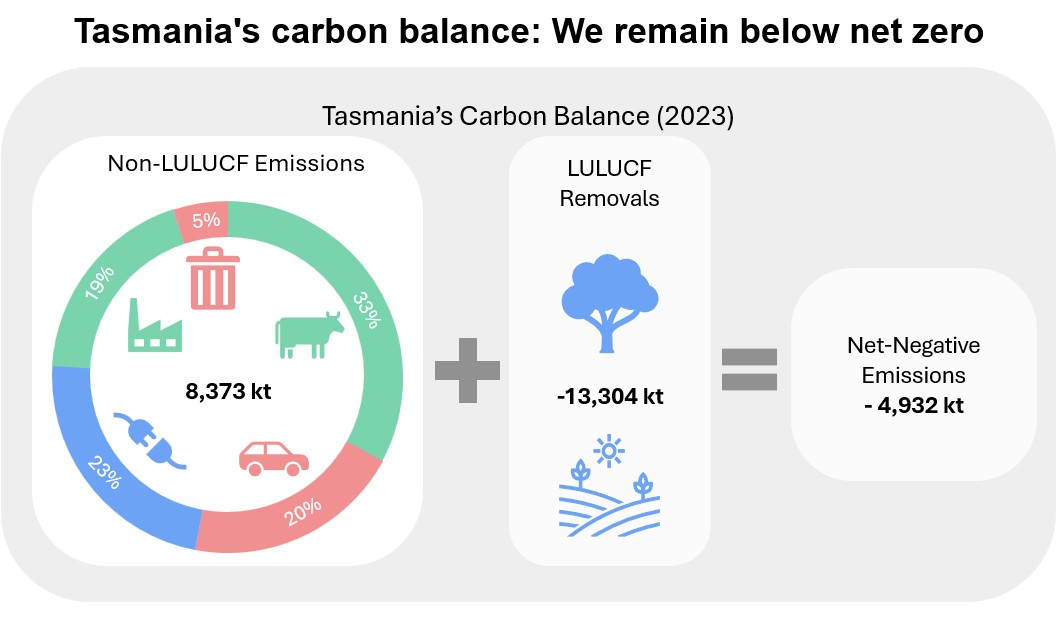

As already mentioned, the good news is that we are still net zero. Not many jurisdictions can make that claim, so we Tasmanians should be rightly proud. As we can see, removals in the LULUCF sector exceeded absolute emissions from other sources in 2023, resulting in net-negative emissions overall (-4,932 kt CO2-e).

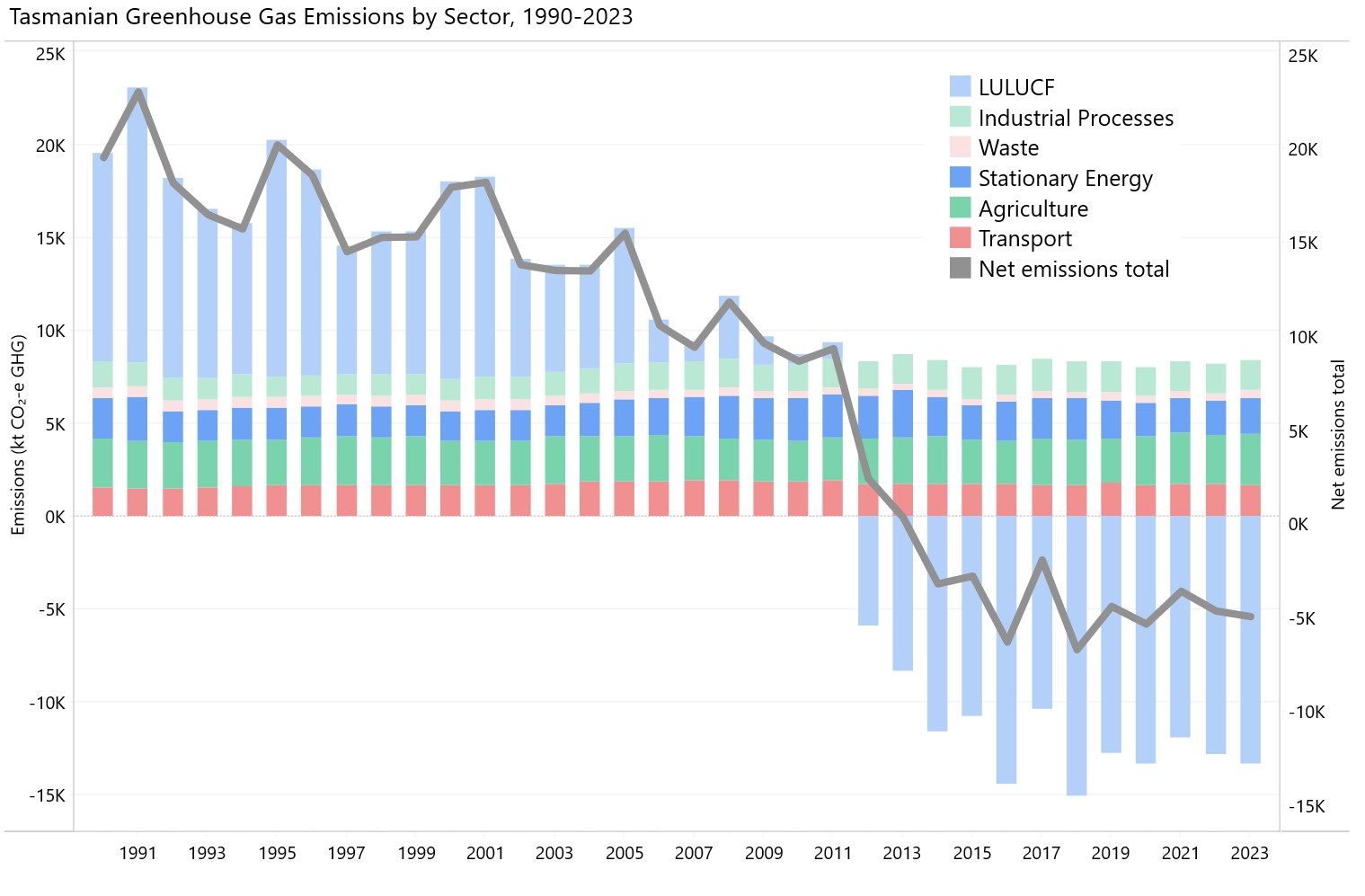

Tasmania’s overall performance, by sector, can be seen below.

While we are still net zero, the picture isn’t all positive. If we continue on our current path, we may not hold onto our net-zero status for much longer. That’s because our carbon removals (the reason we’ve stayed below zero) depend heavily on forests continuing to absorb carbon. As those forests mature, the rate at which they absorb and store carbon will slow until they eventually become carbon neutral. Very quickly, the sustainability of our net-zero status starts to look shaky.

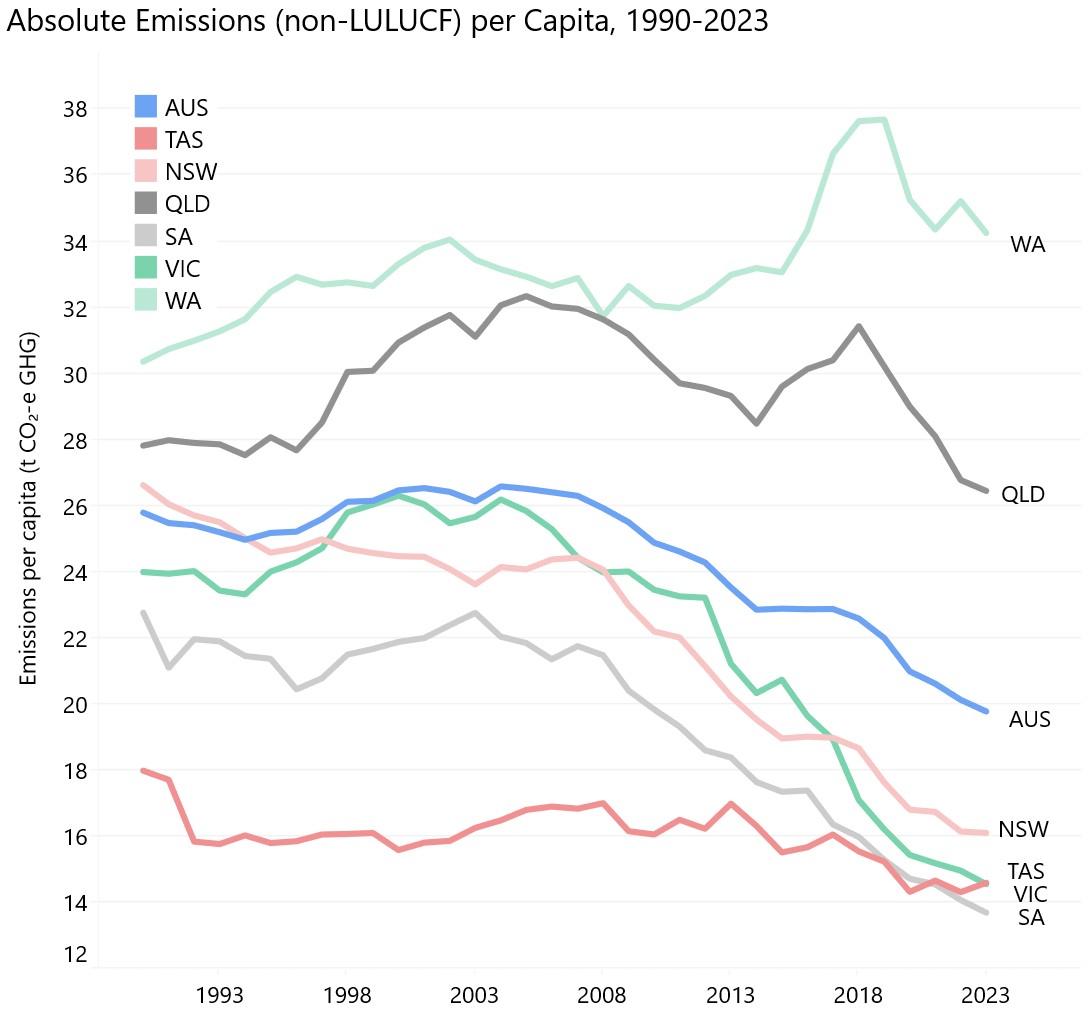

Even more concerning is the fact that we’ve made almost no progress in cutting the emissions we actually produce. This year’s latest data confirms what’s been clear for some time: Tasmania’s absolute emissions have barely moved in decades. And this complacency is costing us.

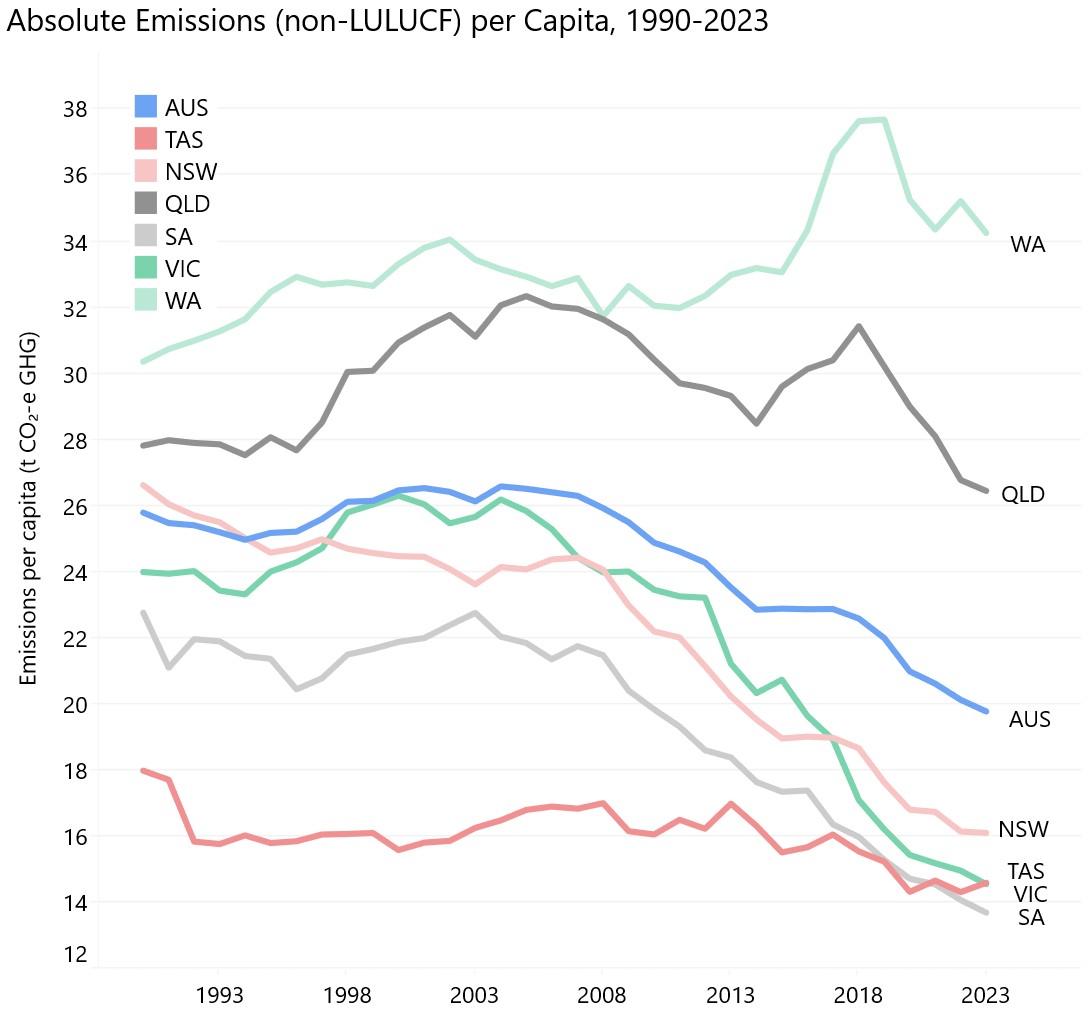

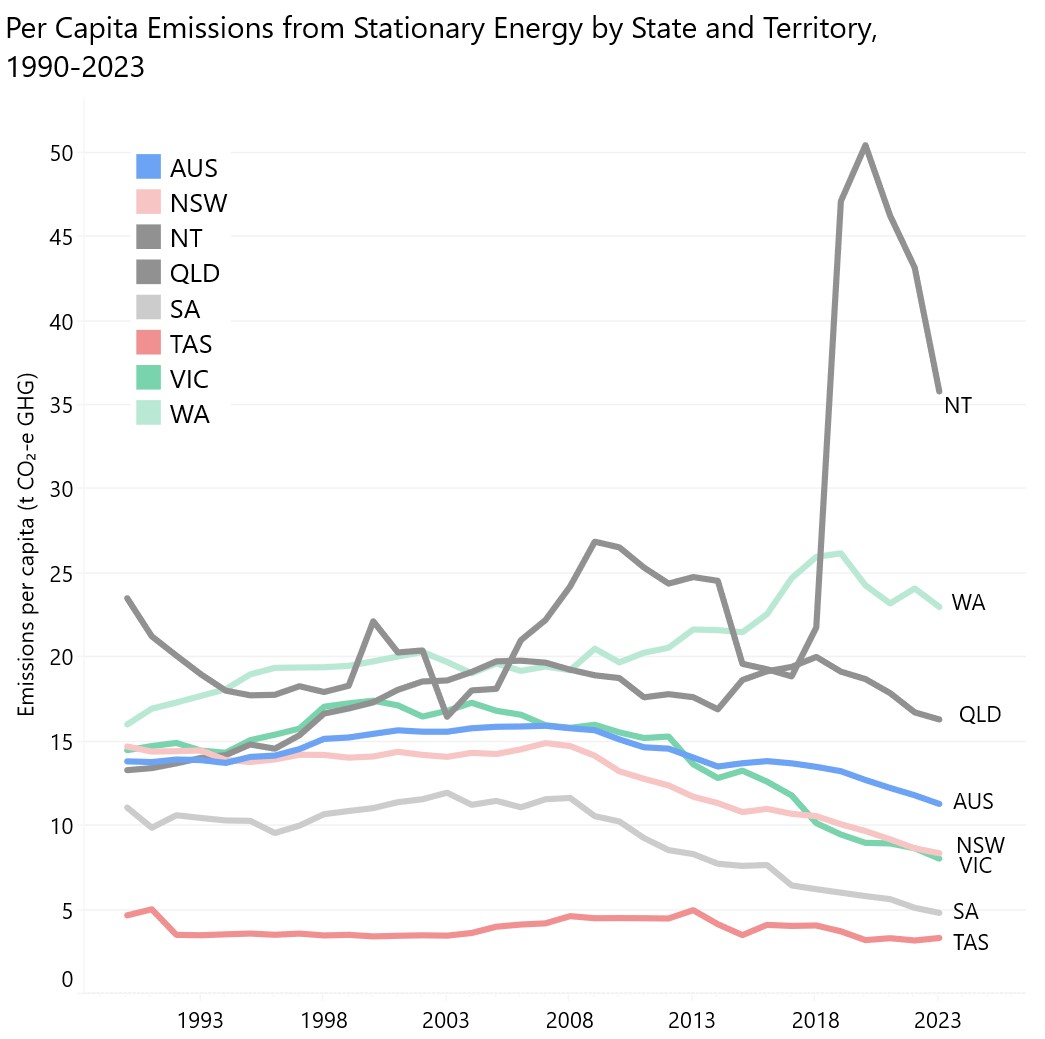

It means Tassie has lost its spot at the top of the leaderboard as the state with the lowest absolute emissions per capita. In2021, South Australia overtook us and as of this year, Victoria has bumped us out of second place. Tasmania no longer leads the country on this key measure. For transparency, it’s worth noting that the ACT actually has the lowest absolute emissions per capita in Australia, and the Northern Territory the highest per capita. Neither is included in the chart above because, as extreme outliers, they distort the visual scale.

This decline in our emissions standing is especially concerning in light of the Tasmanian Government’s recent choices on climate action: The

2025 state budget appears to have made cuts to Renewables, Climate and Future Industries Tasmania (ReCFIT), the agency tasked with leading our emissions reduction and climate adaptation efforts. And since the 2024 election, Tasmania no longer has a specific Minister for climate change.

Given all this, it’s fair to ask: who is accountable for ensuring we meet our 2030 net-zero target, as set out in the

Climate Change (State Action) Act 2008? At a time when leadership and coordination are more important than ever, both appear to be retreating.

Moving Tassie into the future

In order for Tasmania to regain our position as Australia’s lowest absolute emitter per capita, we need to start reducing our reliance on imported fossil fuels and coal-powered energy from the mainland. In this PIMBY, we focus on three key areas where action is both possible and necessary – knowing there are many other areas and opportunities beyond the scope of these three.

Transport

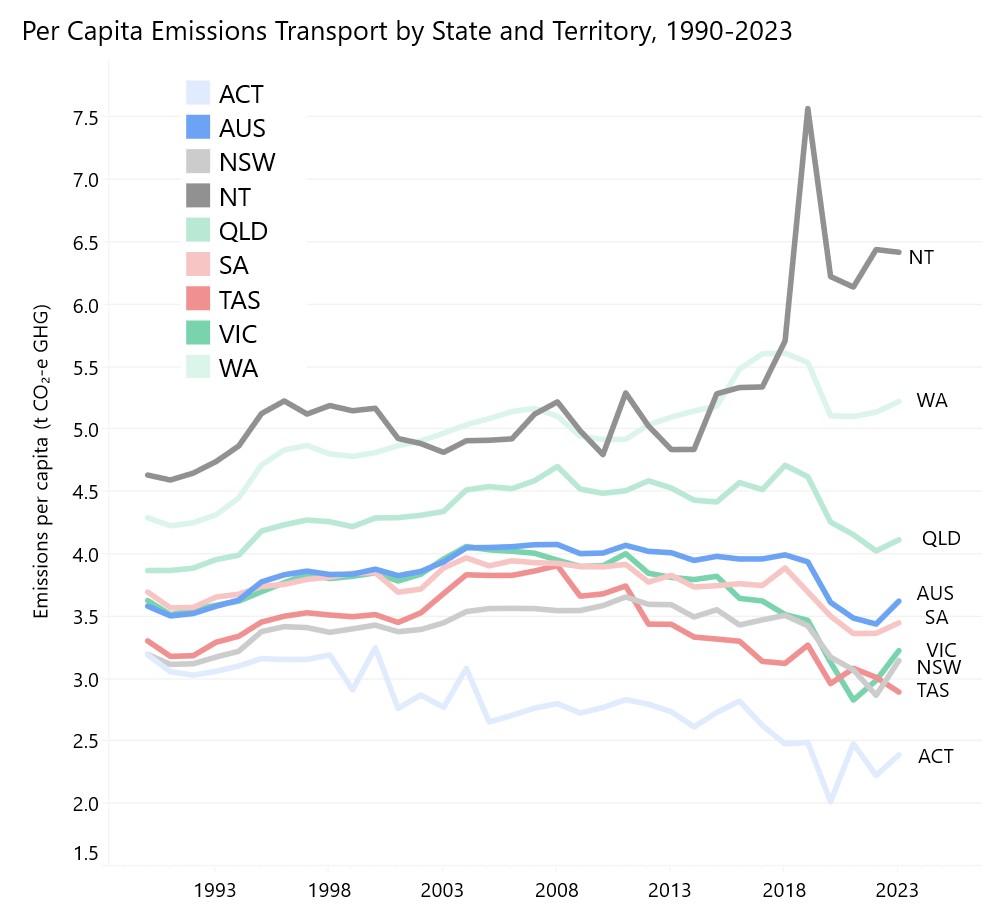

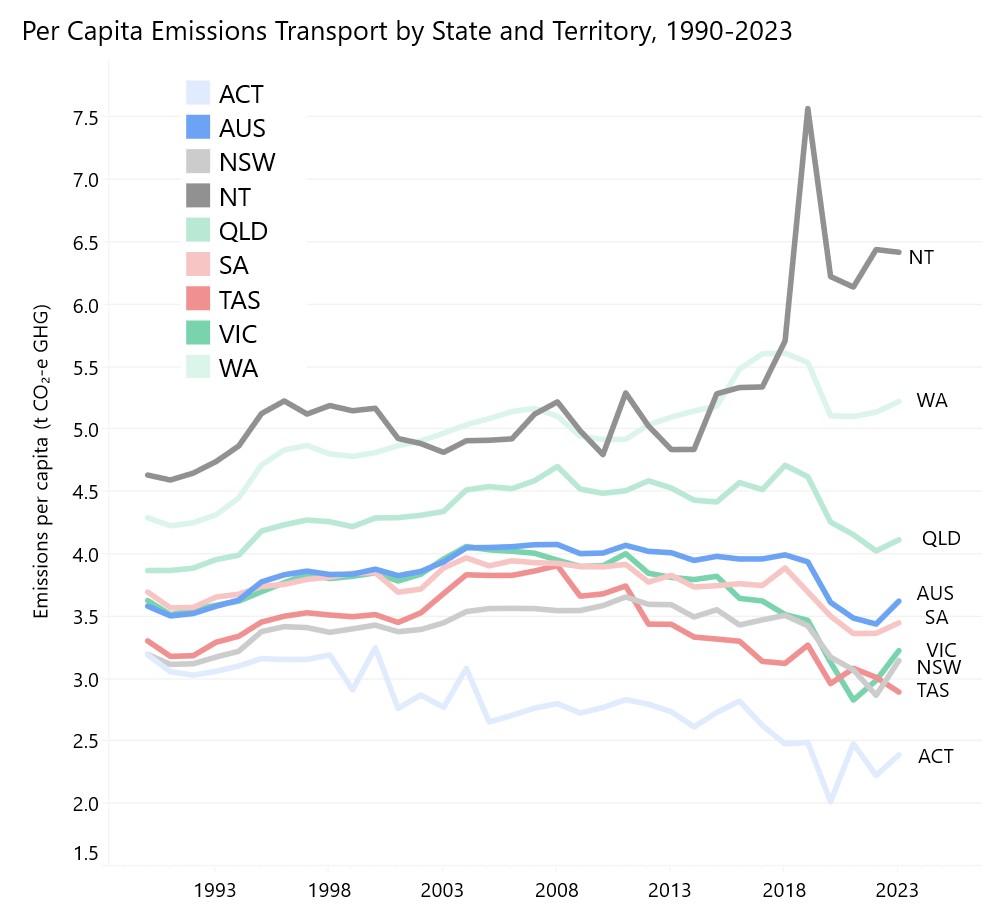

Transport is one area where we are heading in the right direction – but too slowly. Emissions from the transport sector have begun to decline, but we could be doing far more, far faster. Fortunately, many of the solutions already exist, we just need to back them in.

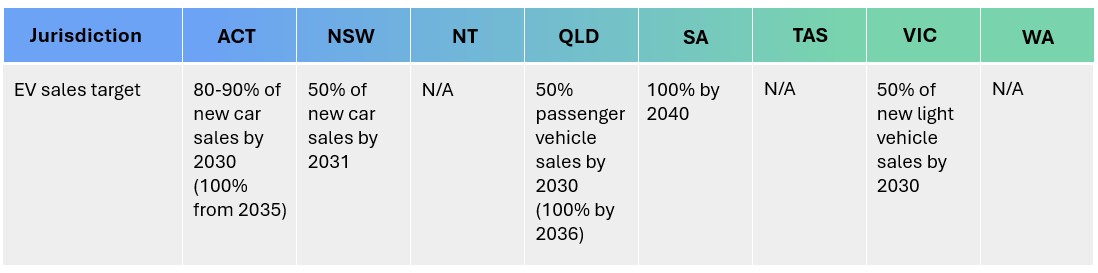

A key place to start is by accelerating the transition to electric vehicles (EVs). That means making it easier, cheaper, and more appealing for Tasmanians to go electric when it’s time to replace their car.

One simple and effective tool is an EV sales target (already used in other Australian jurisdictions) which sends a clear signal to manufacturers and dealers: Tassie doesn’t want to be the dumping ground for internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles when the rest of the world is turning away from them. And we know there is support in Tasmania: in a

2023 TPE survey 60% of respondents supported a 2030 target for EV sales.

Table 1: Light electric vehicles sales' targets in Australian states and territories

Other jurisdictions offer a model we can follow. The ACT leads the nation, with

around 15% of new light vehicle sales now electric. They’ve introduced a few practical measures that make a real difference for households:

- Transitioning vehicle registration fees from a weight-based system to an emissions-based one, which will reward lower-emissions vehicles.

- Waiving new or used EVs from motor vehicle duty. This could be funded through slightly higher duties on ICE vehicles.

- Offering interest-free loans to homeowners of up to $15,000 for sustainable products including new and used EVs and home charging infrastructure.

But cars aren’t the whole story – and they’re not enough on their own.

If we’re serious about reducing emissions to meet Tasmanian and Australian 2030 climate goals, we need to go further. Public and active transport have enormous potential to

reduce emissions and improve health, equity, and liveability. The problem is access and quality. In the TPE survey, 58% of respondents said they would use public or active transport more often if it were more viable in their daily lives. And they also told us that the quality of public transport services was a deciding factor in whether or not they used it. So, reliability, frequency, and safe infrastructure all matter.

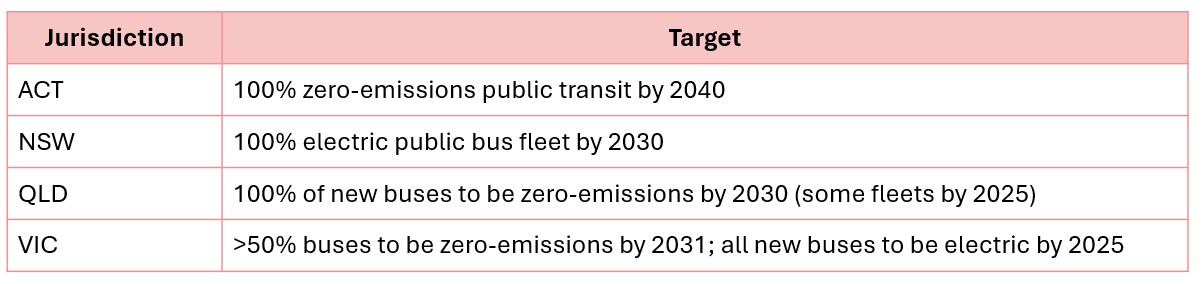

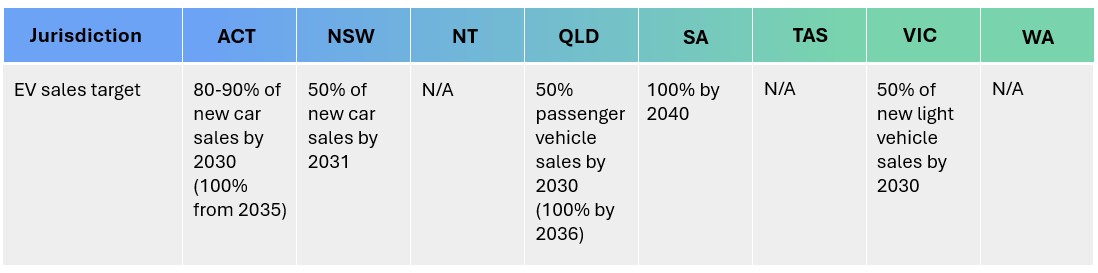

Furthermore, we need a proper statewide plan to electrify our buses. Not just more pilots and trials. Other states have already committed to full bus fleet transition; Tassie should be next.

Table 2: Electric bus targets in Australian states and the ACT

Active transport is another opportunity. Tasmanians are also keen to walk, cycle, or e-scooter. But they need safer streets to do it. According to our survey, far more people will embrace active transport if we invest in:

- Physically separated cycling and walking paths (70%)

- More connected, continuous lanes (64%)

- Slower speeds, car-free zones, and traffic calming strategies (52%)

This is low-hanging fruit. The benefits go beyond emissions to touch everything from road safety to public health and the cost of living. All that’s missing is a coordinated plan and the willingness to see it through.

Agriculture

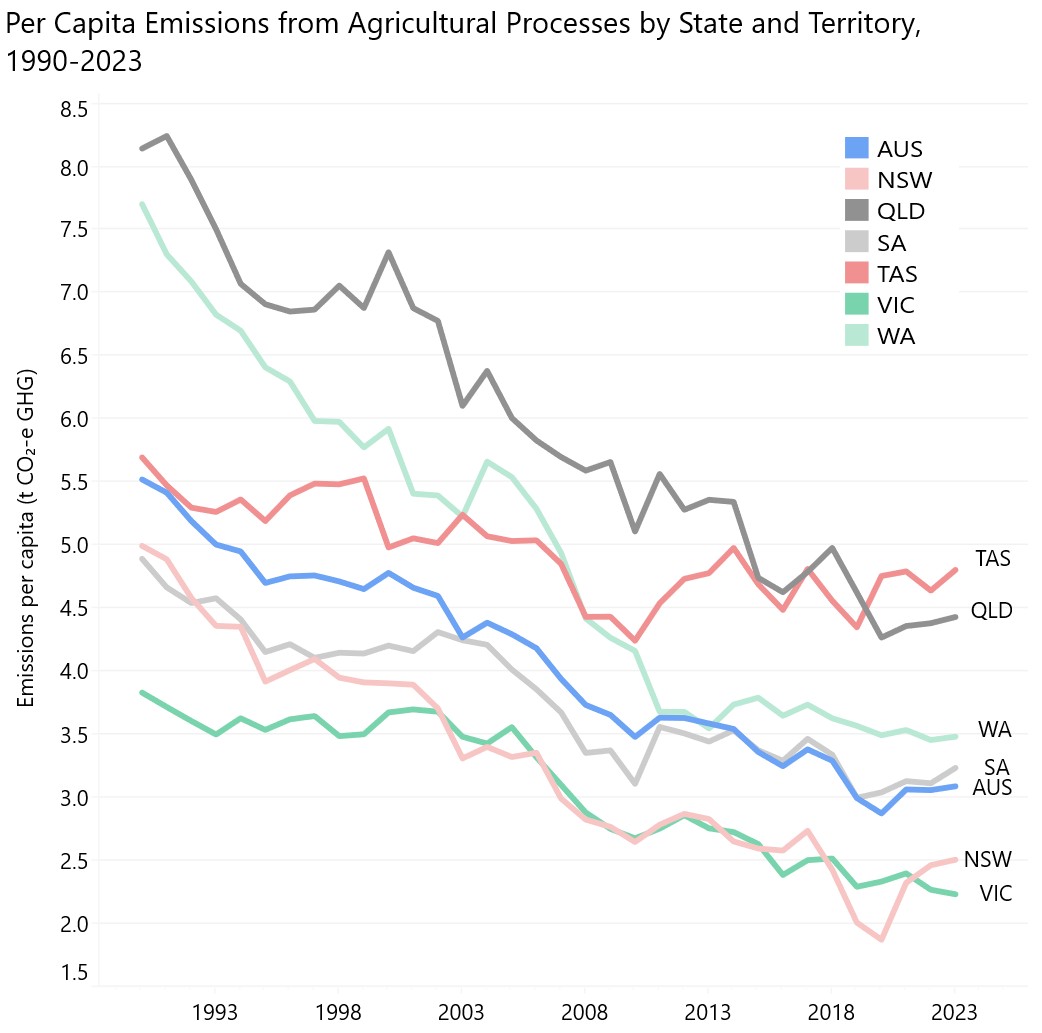

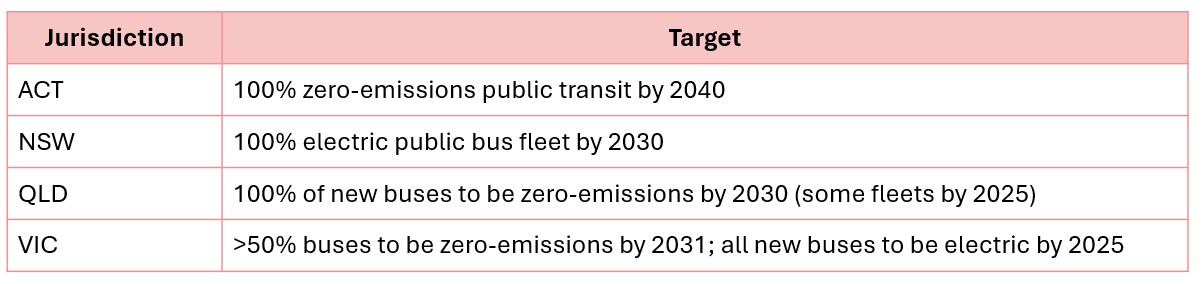

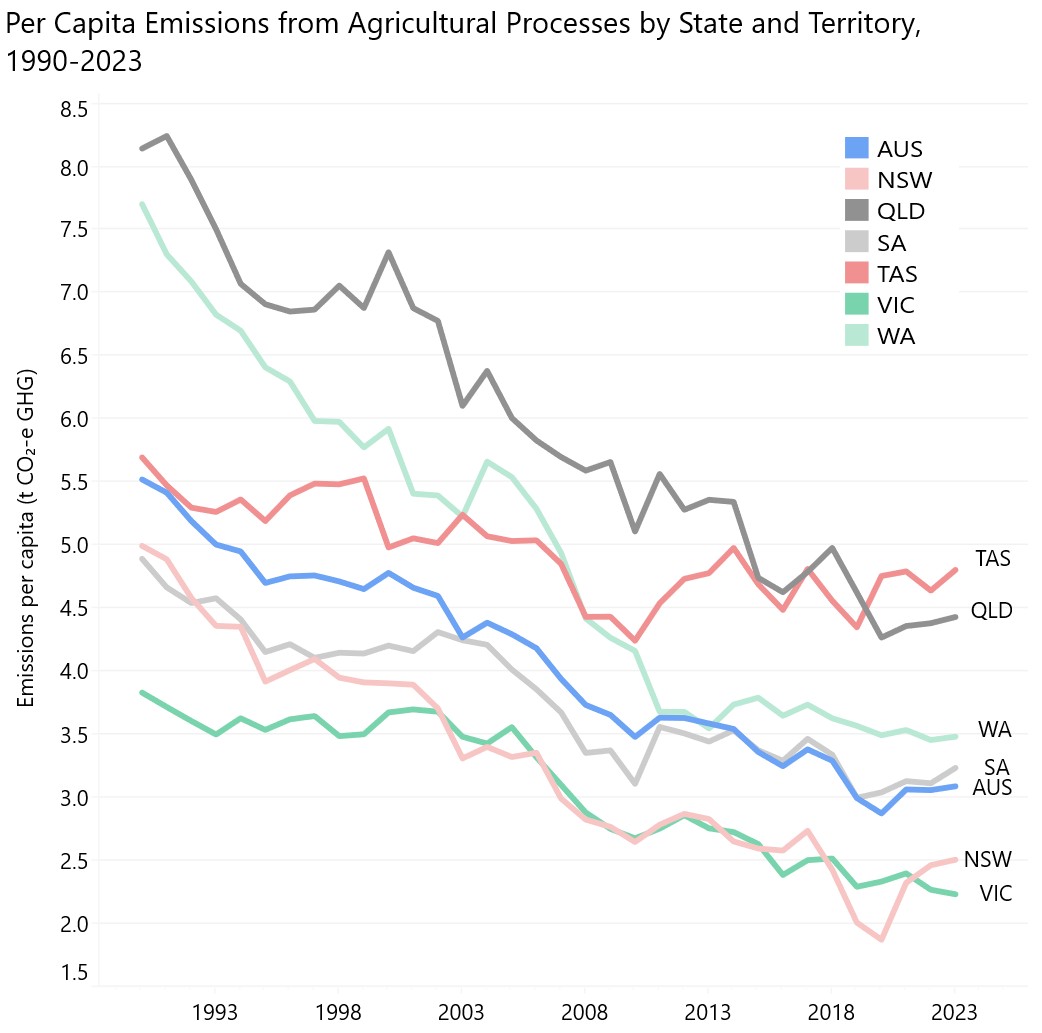

Tasmania has nation-leading (in the worst way) per capita emissions in agriculture… And they’re trending in the wrong direction.

This matters not just for climate reasons, but also because the agriculture sector is central to our economic future. The Tasmanian Government has set a target to grow agriculture to a

$10 billion industry by 2050 – a target that will require the sector to double its growth rate over the next 25 years. If we don’t decouple that growth from emissions, we risk undermining both climate goals and the sector’s competitiveness.

Agriculture is Australia’s largest source of methane emissions, most of it from burping livestock. One of the most promising solutions is

Asparagopsis seaweed feed – a supplement that can

reduce methane emissions from livestock by as much as 95%. We even have a Tasmanian front runner in this technology, with local producer Sea Forest ramping up land-based seaweed farming at Triabunna.

But right now,

SeaForest is selling to a supermarket chain in the UK, because UK farmers are financially rewarded for adopting this methane-reducing practice. In contrast, Australia’s carbon credit scheme still doesn’t include

Asparagopsis. That’s a missed opportunity for both emissions and local innovation.

Soil carbon sequestration projects offer another promising way for farmers and other land managers to improve soil health and raise productivity all while lowering their emissions. Eligible applicants can currently access advance payments

up to $5,000 to assist with upfront establishment costs for soil carbon projects under the Australian Carbon Credit Unit (ACCU) scheme, but only

four projects have been registered in Tassie so far.

Raising awareness and scaling up the use of these agricultural emissions reduction tools isn’t just good for the climate, it’s good for farmers too. Research shows that both

Asparagopsis feed supplements and

soil carbon projects can boost farm productivity and profitability. If we want to grow our agriculture sector in a sustainable way, now is the time to scale up these solutions. We can send a clear policy message that low-emissions agriculture is the future.

Renewable energy

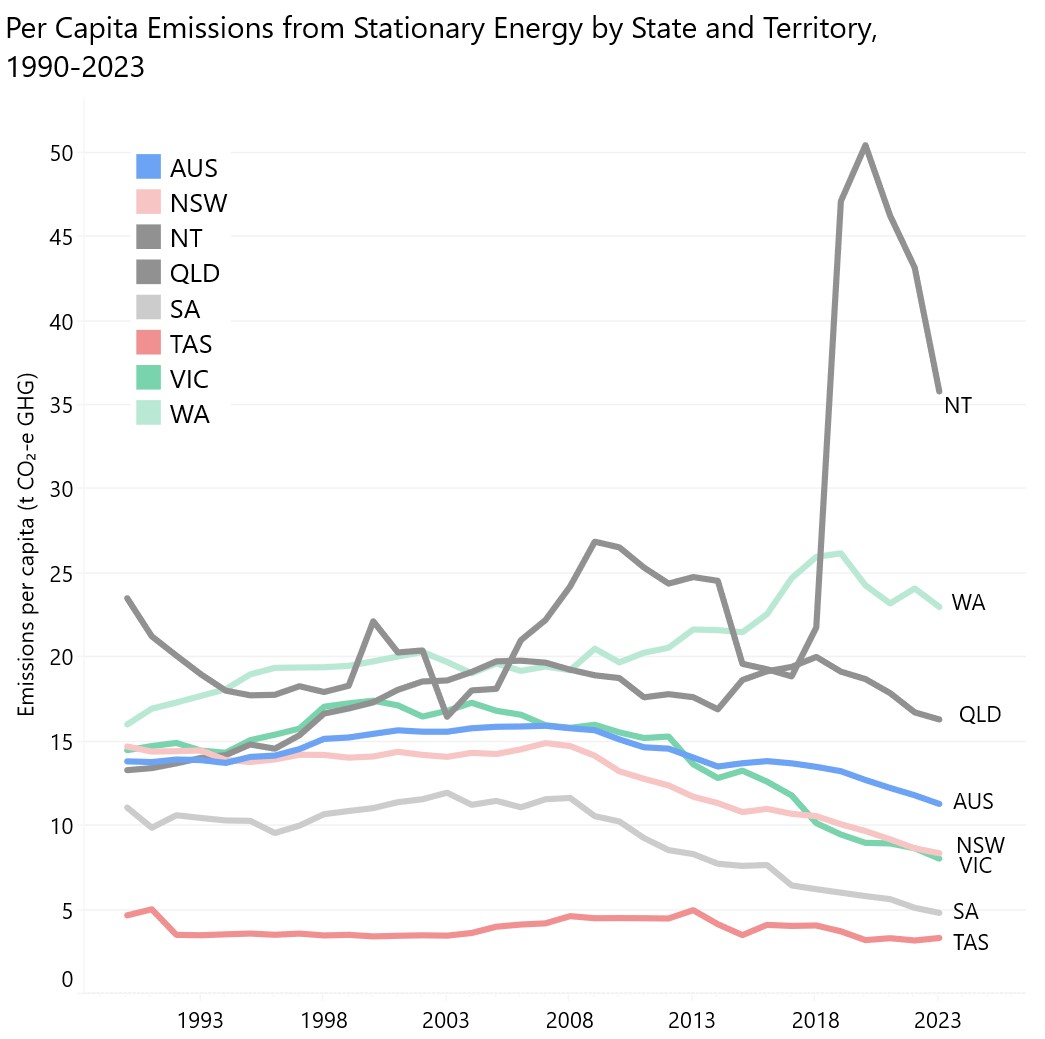

Tasmania has the capacity to be 100% powered by renewable energy and, at times, we do generate enough hydro and wind energy to meet our electricity needs. But the reality is more complicated.

In

four of the past five years, Tasmania has been a net importer of electricity. We rely on electricity from the mainland, including from fossil-fuel sources, when local generation can’t cover our energy needs. Beyond electricity, we still mostly use fossil fuels to power our cars, heavy vehicles, and industrial processes. In fact, fossil fuels still provide

approximately half of Tassie's total energy. While our stationary energy emissions remain low compared to other states and territories, they’ve also barely budged over the past 30 years.

In order to decarbonise, we will need to develop increased renewable energy capacity, especially in dry spells when we choose to conserve water instead of using it to produce hydroelectricity. This will only become more critical as electrification drives up local demand.

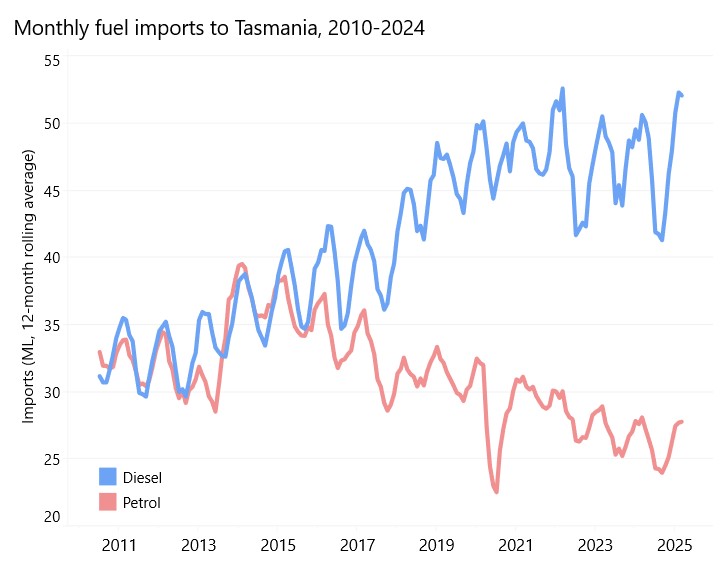

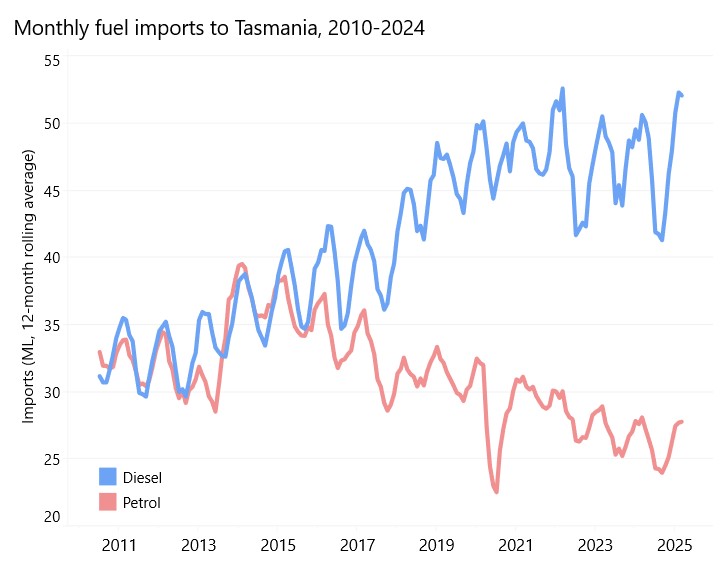

We also need to tackle Tassie’s growing diesel dependency. While petrol use has declined over the last 15 or so years (likely due to more fuel efficient and zero-emissions vehicles) diesel imports have been steadily increasing.

That’s a problem, especially for heavy transport and industry, which remain hard to electrify with current technologies. This is where clean fuel alternatives like biofuels, synthetic fuels, and biomass energy solutions are promising for industrial heat generation and for heavy vehicle applications for which electric batteries are not suitable. Renewable diesel would be a particularly convenient “drop-in” replacement for diesel derived from fossil fuels.

These aren’t science fiction – they’re already being trialled on the ground. For example, the Cleanaway trial of Volvo trucks in Victoria (one picking up kerbside waste and the other, organic waste from Coles supermarkets), run on HVO100 renewable diesel. After eight months:

- CO2-e emissions dropped by an estimated 124 tonnes

- Fuel filters remained cleaner than expected

- Fuel efficiency matched that of standard diesel

- Drivers reported no difference in power delivery

The results are promising but, as with any new technology, we need to proceed with caution. The hope is that these “clean” fuels can help lower emissions, but clean fuels must be affordable, sustainable and ethical. We must also remain vigilant to avoid unintended consequences, such land competition with other important uses or unsustainable forest harvests.

It may be the case that in the medium term, renewable diesel may provide a transitional solution until better options, like lighter batteries with longer range, become widely available. If you have thoughts on clean fuels and their production and/or use in Tassie, the Government’s draft Future Clean Fuels Strategy for Tasmania is open for comment until 4 July 2025.

Beyond net zero

We’ve spent a lot of time talking about what it means to be net zero, and some options for what we can do better. The bottom line is this: not much has changed where it really counts. Our actual emissions have barely shifted. Other states aren’t just catching up; some have already overtaken us. This isn’t just about bragging rights, it will make it harder for Tassie to attract investment, access increasingly carbon-conscious markets and support clean industries of the future.

That’s why it’s time to start thinking beyond net zero. Because we can do better than simply holding ground – we can actually make progress.

This PIMBY article has laid out just a few of the things we can do right now: from accelerating EV uptake and scaling up low-emissions agriculture, to investing in more local renewable electricity generation. These aren’t far-off dreams or hypothetical technologies. They’re real, tangible actions – many already working in other places that could start making a difference today.

Yes, global and local politics are currently dominated by other issues. Yes, housing, health, and the cost of living are understandably dominating political conversations. But the climate crisis hasn’t gone anywhere. It’s aright now problem and there are right now solutions available.

Tasmania still has the chance to lead. But that won’t happen without intentional effort, government action and community commitment. It will take shifting away from treating emissions as an abstract or symbolic goal, and toward incentivising real, widespread action.

Because if we want to move beyond net zero, we can’t afford to stay still.