produce more – be it commercial products or public services– in same

amount of time, our labour becomes more valuable. This means more money for the same hours of work or fewer hours of work for the same return, or both.

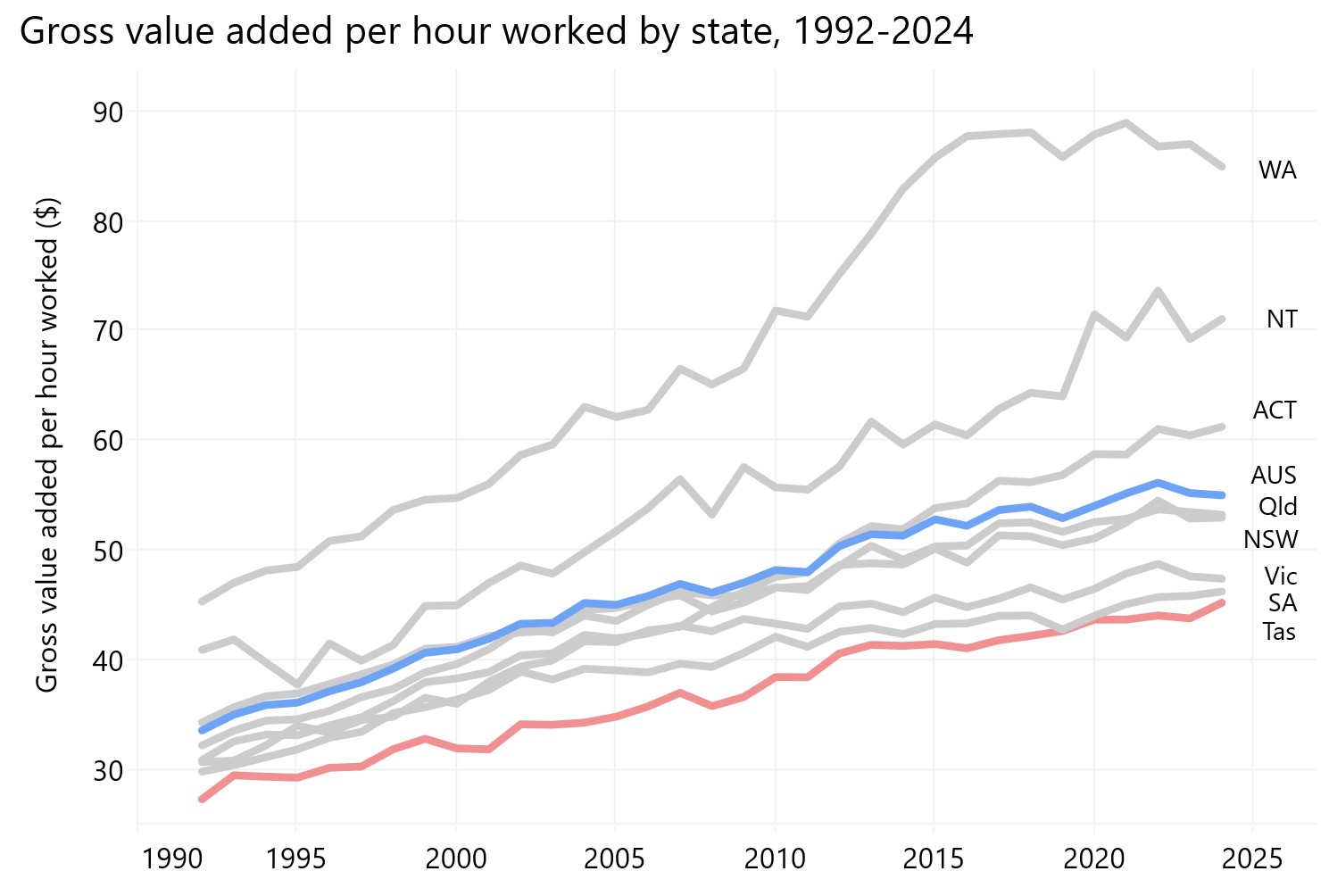

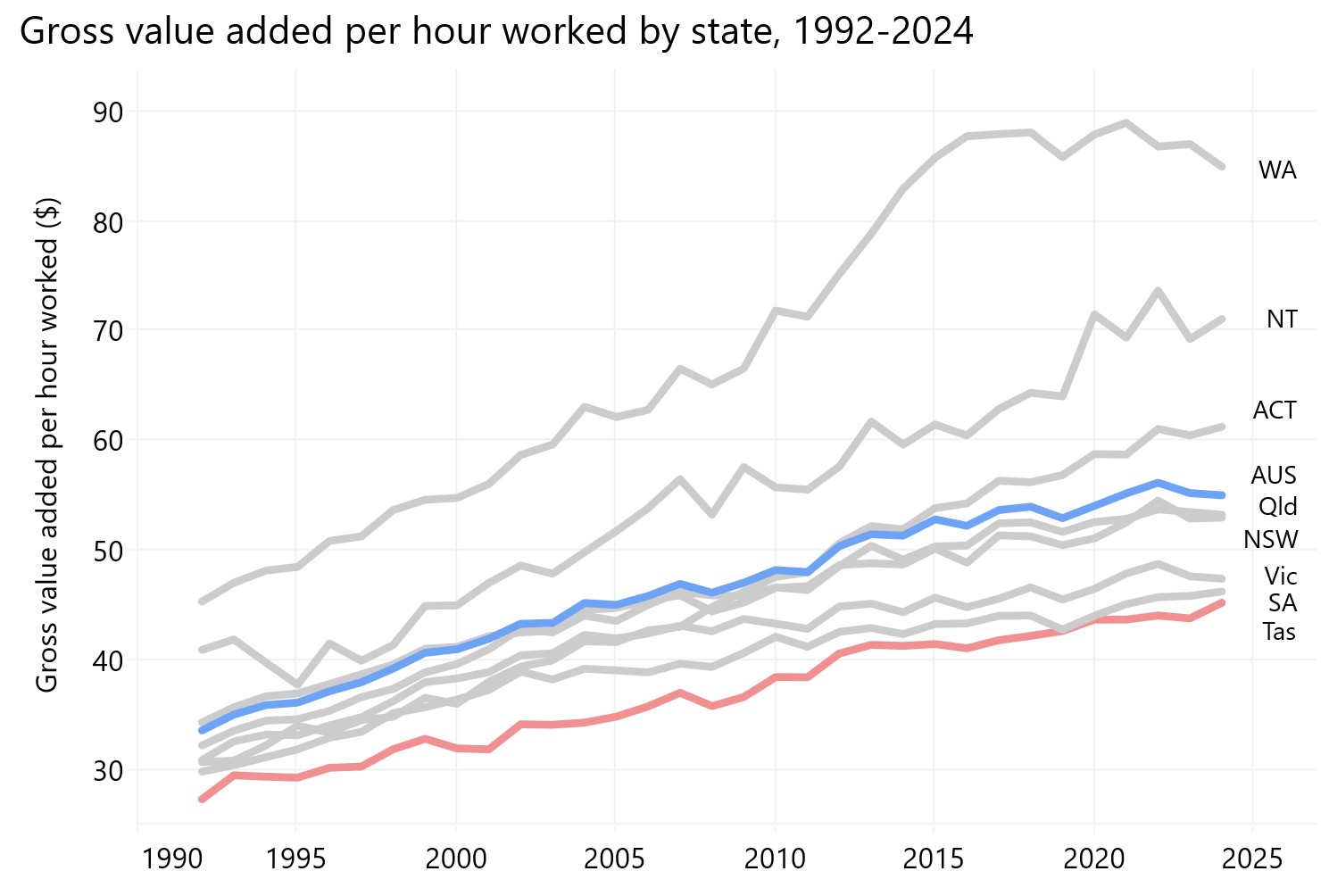

But according to traditional measures, productivity growth has slowed dramatically across the developed world in the last couple of decades. In Australia, the average annual growth rate since the COVID pandemic is now crawling along at less than half of what it was in the 1990s. The situation is even more serious here in Tasmania. On most measures, Tasmania is already the least productive state in the nation which, when combined with our slower economic growth, sees us slipping further behind the mainland states every year.

With productivity firmly back on the political agenda, this edition of PIMBY takes a closer look at what productivity is, why it matters, and how Tasmania compares with other states. We’re also interested in examining more contemporary and holistic definitions of productivity and reforms that will enhance community wellbeing and environmental sustainability. Following next month’s

National Productivity Roundtable, we’ll be back with another piece on policy options for growing productivity here in Tasmania and in other regional economies.

Four things to know about productivity

Before we talk about what productivity means for Tasmania, it’s worth taking a moment to outline the basics of the current productivity debate.

1. What is productivity and how do we measure it?

According to economics textbooks,

productivity is the efficiency with which we turn inputs (like resources and labour) into outputs (like goods or services). To measure a worker’s productivity (known as ‘labour productivity’; we won’t get into

capital and multifactor productivity), you divide the value of their output by the number of hours they spent producing it. So, if a factory comes up with a way to make six solar panels in the time it used to take them to make five, it’s increased productivity by 20%.

However, in a large and growing slice of the economy, measuring productivity is more complicated than this. For example, doubling the number of students in a classroom won’t make teachers more productive. Discharging patients early doesn’t make for a more productive hospital. Measuring productivity in sectors like these (especially when they’re provided by the government rather than the market) requires a more nuanced understanding of the quality, effectiveness, and public benefit of the ‘output’ being produced.

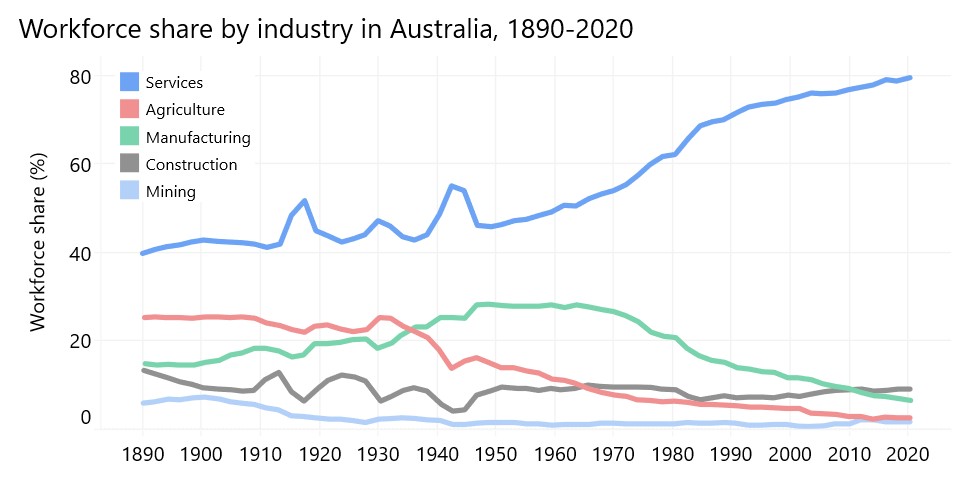

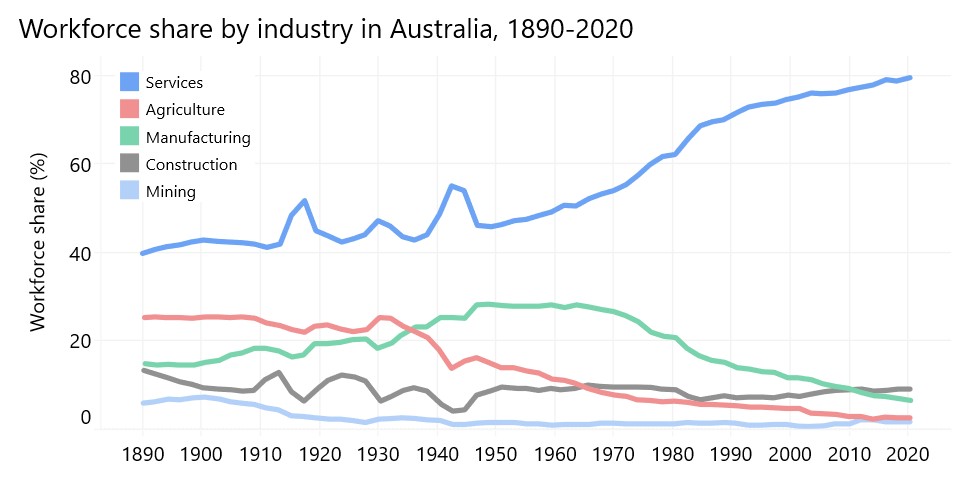

As we outline below, the productivity debate rightly extends beyond narrow economic measures to consider how we can provide more effective, quality services in sectors where output can’t easily be reduced to a simple market price. This focus on services, sustainability and valuable work like volunteering or caring (what economists call ‘non-market goods’) matters because the structure of our economy and society has changed in ways that have fundamentally reshaped how we should think about productivity. Back in 1890, more than 60% of Australian workers were employed in industries like manufacturing, mining, and construction, where measuring productivity is pretty straightforward. Today, more than 80% of total employment is in the services sector, which means that accurately measuring productivity is harder now than it’s ever been.

2. Why is productivity growth slowing down?

The most recent 5-year Productivity Inquiry Report from the Productivity Commission sets out to explain of Australia’s poor productivity performance and come up with options for addressing it. The final report is over 1000 pages long, with 29 reform directives and 71 specific recommendations. In other words, productivity growth is complex and there’s no single reason it’s been slowing down. Broadly speaking though, there are a few important factors at play:

- A less dynamic business environment. In Australia today, fewer people are starting businesses than they used to, and fewer businesses are going bust. These businesses invest less in innovation than they once did. Partly this is because they don’t need to – interest rates have been low, big firms have gotten even bigger, and corporate profits have soared. Workers themselves are also less likely to change jobs or move cities than they once were. Some of these might seem like good things, but the overall impact has been bad for productivity because it’s made our businesses less innovative, less efficient, and less competitive.

- Slower ‘diffusion of knowledge’. Innovation and productivity growth have long been driven by a small number of highly innovative firms. But these days, the flow of new ideas and technologies from these so-called ‘frontier firms’ to the rest of the economy has slowed. Reasons for this include tighter intellectual property protections, the use of non-compete clauses in employment contracts, and a growing concentration of talent in a small number of very large companies.

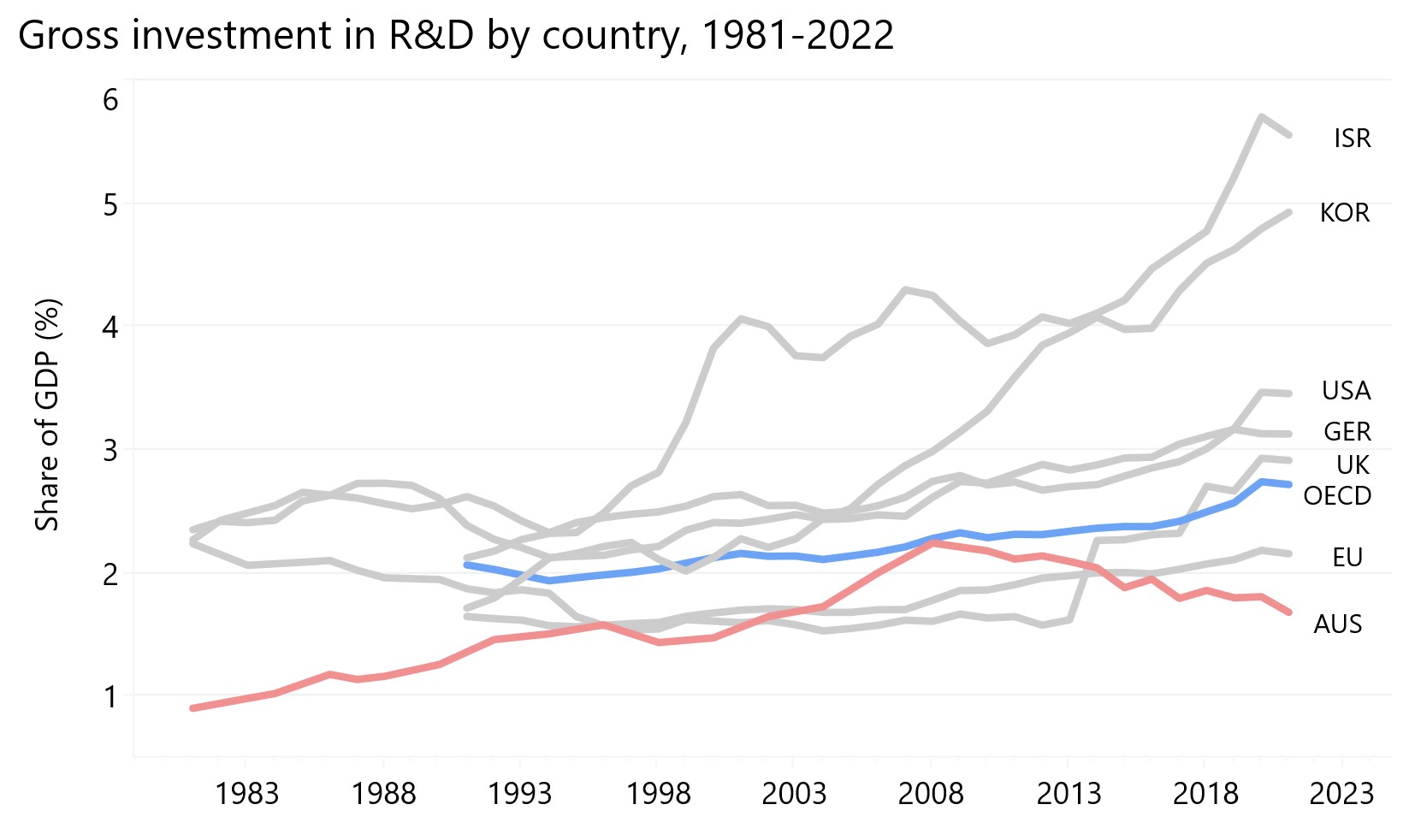

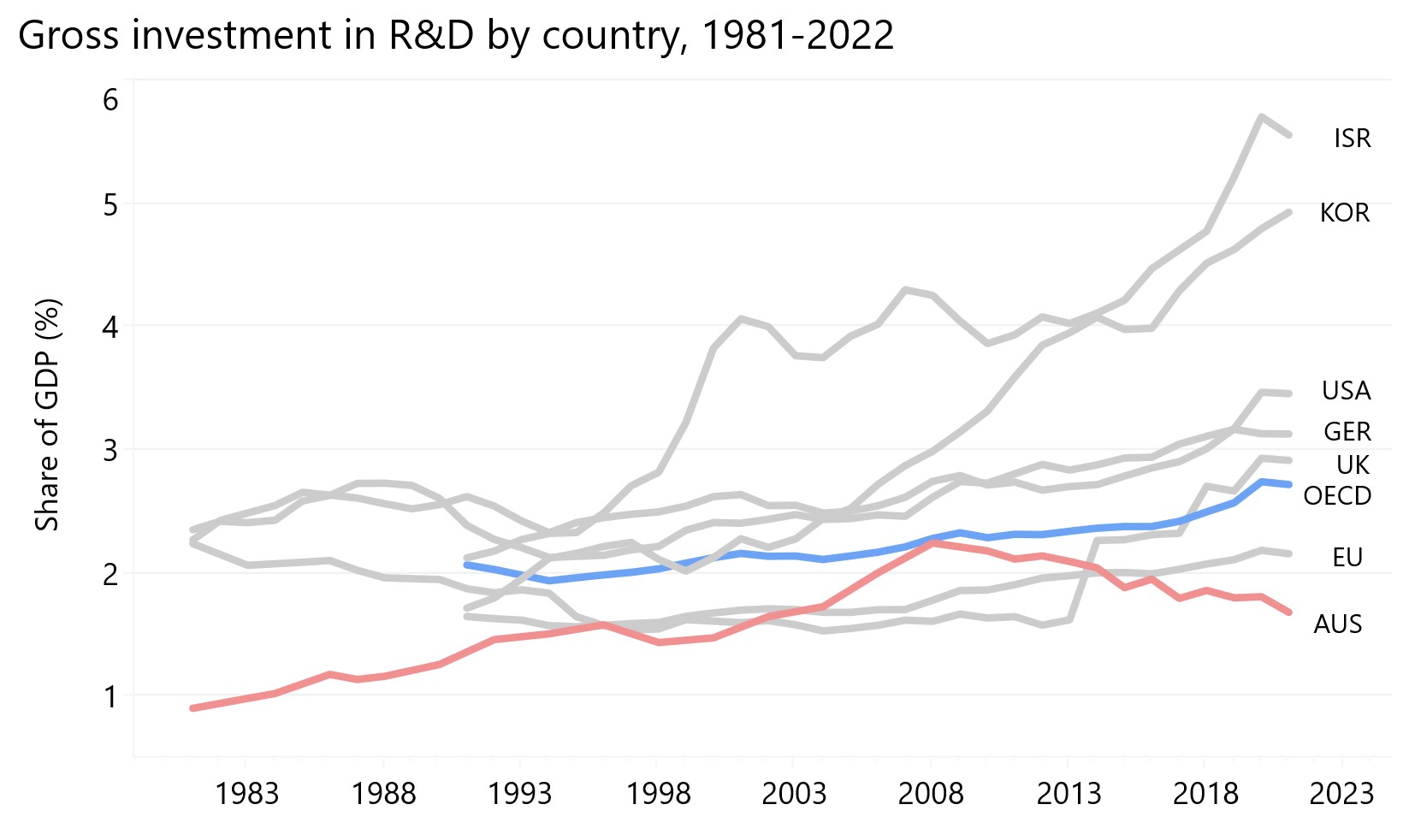

- Falling R&D investment and innovation. One of the single most important drivers of productivity growth is the development and application of new technologies and ideas, which doesn’t happen without significant and sustained investment in research and development (R&D). Australia has never been great at this, but we’re getting worse. Since the global financial crisis, Australia’s gross R&D investment has steadily declined, even as the world’s major innovation powerhouses have doubled down.

Above all, research on productivity highlights the need to support the development of innovation ecosystems where education, training, and research efforts are aligned with regional community and industry needs and embedded in service and business models. Tasmanian agriculture is a good example of how collaborative research through the Tasmanian Institute of Agriculture, combined with investment in training, technology and infrastructure such as irrigation, have delivered significant productivity dividends.

3. What’s the connection between productivity and sustainability? Productivity is fundamentally about how efficiently we use materials and resources, which means it has major implications for the environment. As well as making us more prosperous or giving us more free time, productivity growth can lessen our impact on the planet, reduce waste, and conserve natural capital. We must ensure that productivity reforms enable us to live more sustainably, rather than pursuing growth at any cost.

Right now, our unsustainable economic model is damaging the environment in ways that actually hurt productivity. For example,

climate change is already eroding productivity through rising demand for health services (during heatwaves and natural disasters), and degradation of ecosystems that provide resources like clean water.

It’s sometimes argued that addressing climate change and transitioning to renewables will hurt productivity growth. This view simply could not be more wrong. Climate change is probably the biggest single risk to productivity in the 21st century, and green innovation is one of the greatest opportunities for growing it. The Productivity Commission review rightly identifies a carefully planned transition to renewable energy and zero-carbon industries as a key national productivity priority.

That’s why some economists are calling for new ways to think about concepts like productivity and their implications for the environment. One example is

Kate Raworth’s doughnut economics, which promotes a more circular, sustainable model that keeps our production systems working within social and planetary boundaries.

4. What (and who) counts as productive?Finally, we need to ask what kinds of work, and indeed which workers, we think of when we measure productivity. Some kinds of labour and value aren’t accounted for in traditional measures of productivity and, unsurprisingly, the omissions tend to be deeply gendered. For example, unpaid work (

typically ‘women’s work’ like domestic labour and caring responsibilities), is excluded from productivity calculations despite being essential to our society and economy, highlighting the need to consider broader measures of public value.

Even within the ‘formal’ economy, productivity is hardest to measure in critically important service sectors that disproportionately employ women. Much of the

‘output’ of education, care, and the public sector is hard to quantify. As a result, most productivity metrics underestimate the importance of quality, particularly in labour-intensive service and caring jobs that dominate the Tasmanian economy.

Take healthcare, for example. According to standard measures, healthcare is a drag on Australian productivity that weighs down our average rate because it employs so many people. However, sophisticated new experimental measures of quality-adjusted productivity suggest that Australia may in fact have one of the

world’s most productive healthcare sectors, with growth rates more than three times the national average.

The rapid growth of social media and the online ecosystem points to further limitations with traditional measures of productivity. Consider a platform like Facebook Marketplace: we aren’t aware of official data on the annual value of Marketplace sales, but it must surely be in the hundreds of millions of dollars, at least. As a ‘free’ service that facilitates trade between individuals, neither the financial value of Marketplace transactions nor the platform’s less tangible benefits to users are included in GDP (and therefore productivity).

There are hundreds of similar examples and they add up to a staggering volume of economic activity that flies below the productivity radar. All of this highlights a bigger and more important point: growing productivity matters, but it’s not the end of the story. How we define and measure productivity matters too. If we rely on narrow metrics that overlook quality, equity, unpaid work and the informal economy, we risk drawing the wrong conclusions and focusing on the wrong solutions.

Tasmania's productivity performance

In addition to the national challenges we’ve outlined above, Tasmania has some specific productivity problems of its own. On most key economic and social metrics, Tasmania lags the rest of the country and it’s no surprise that productivity growth suffers as a result.

Since the early-1990s,Tasmanian labour productivity has grown by around 29%. National growth over that time was close to 40%. If we’d kept pace with the rest of the country, the median Tasmanian would probably be earning over $100 more per week than they are now.

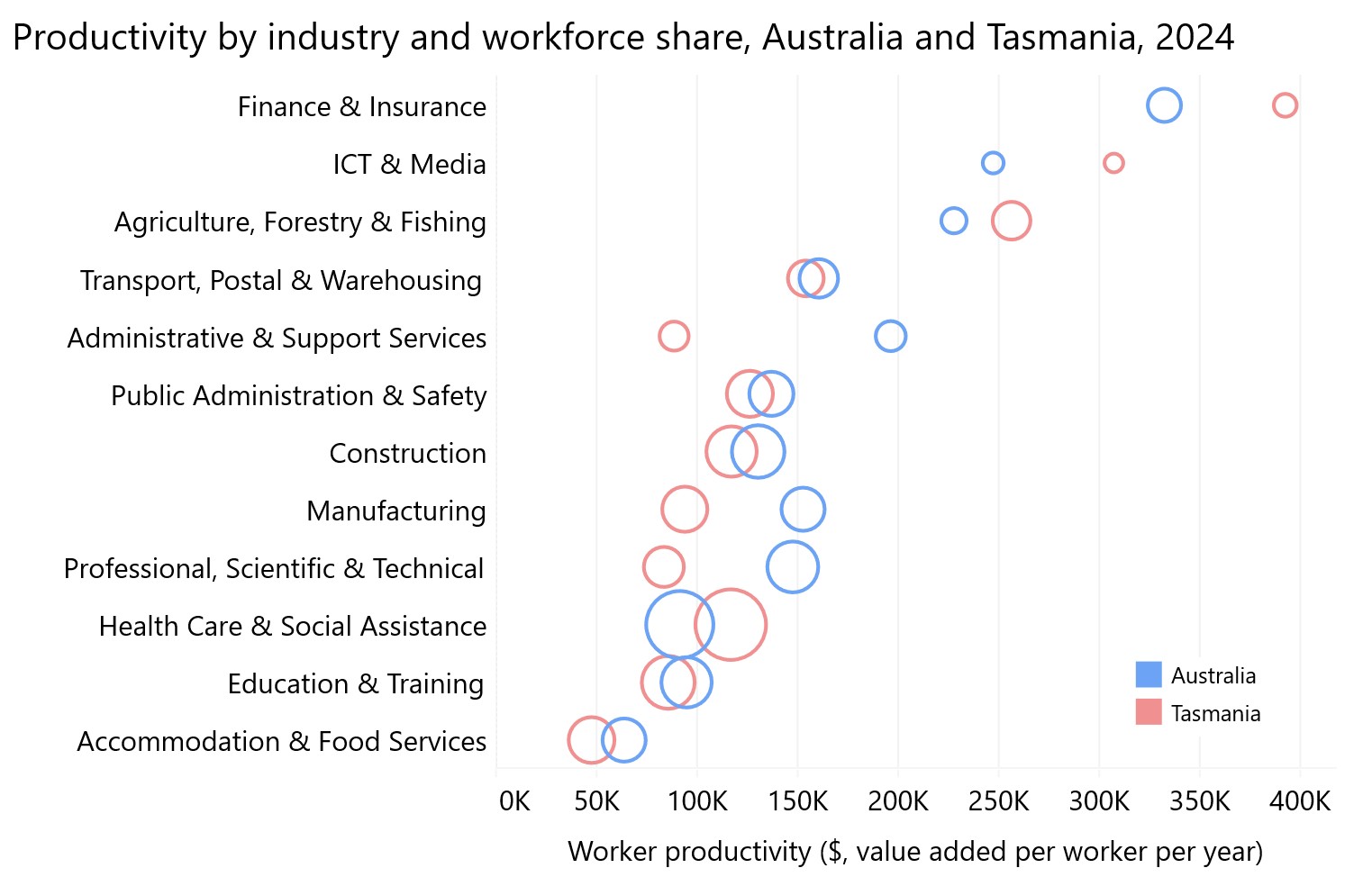

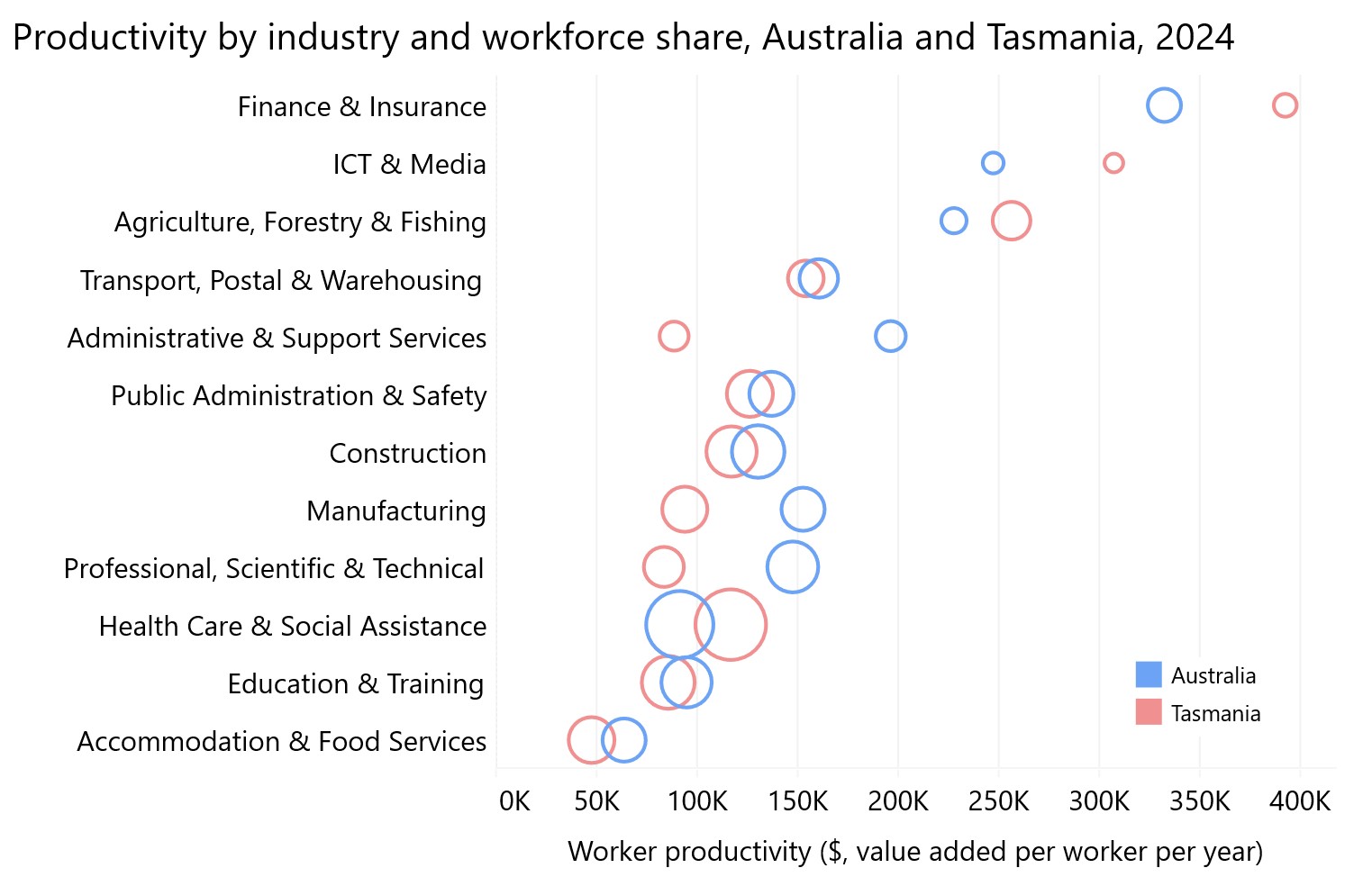

More detailed analysis of Tasmania’s productivity performance by industry highlights variations on this theme. Tasmania’s economy is dominated by less productive industries and, even within these industries, Tasmanian workers tend to produce less than their mainland counterparts. There are exceptions, though. Tasmanian labour productivity in some parts of the agriculture, ICT, and finance sectors exceeds the national average, although these industries combined account for only about 8% of jobs in Tasmania. Our large healthcare and social assistance sector is also slightly more productive than the mainland average, but continuing to improve the availability, quality and effectiveness of care must be a critical priority for government and community alike.

Source:

idProfile Tasmania. Bubbles are scaled to represent each industry's share of total employment.

Tasmania also needs to invest more in local innovation and R&D.

ABS data show that the share of Tasmanian businesses who report being actively engaged in innovation activities is the lowest of any Australian state or territory. As noted above, we’ll spend more time on the policy response to these and other Tasmanian productivity challenges in a future post.

What is productivity for?

This PIMBY has given an overview of the productivity debate and briefly discussed Tasmania’s productivity predicament, but we’ve really only scratched the surface. Over the coming months, our work and that of the University will focus on working with partners to reconsider Tasmania’s productivity debate in a way that prioritises community wellbeing and environmental sustainability in our Island state.

We believe that productivity growth is important, but the most important question we need to answer as a community is, why? Productivity is growth should be pursued as a means to an end rather than for its own sake. This means that we all need to proceed with a clear-eyed understanding of what productivity gains will buy for us, whether that be more time, more stuff, or more and better-quality public services.

Finally, we need to stay mindful of all the ways that traditional productivity metrics undervalue less tangible but essential features of economic output. Unless we’re measuring what matters, we’ll risk focussing our effort in the wrong places.