So, what is the fundamental problem?

Saul Eslake’s Review and last

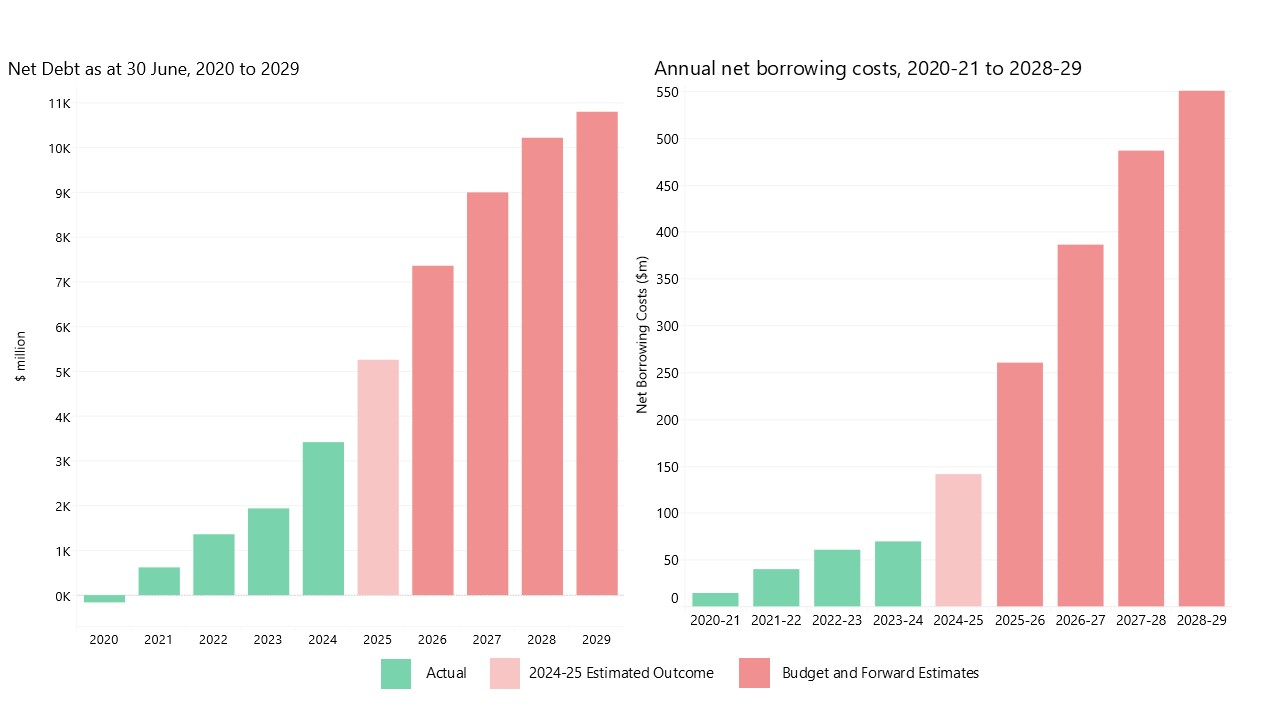

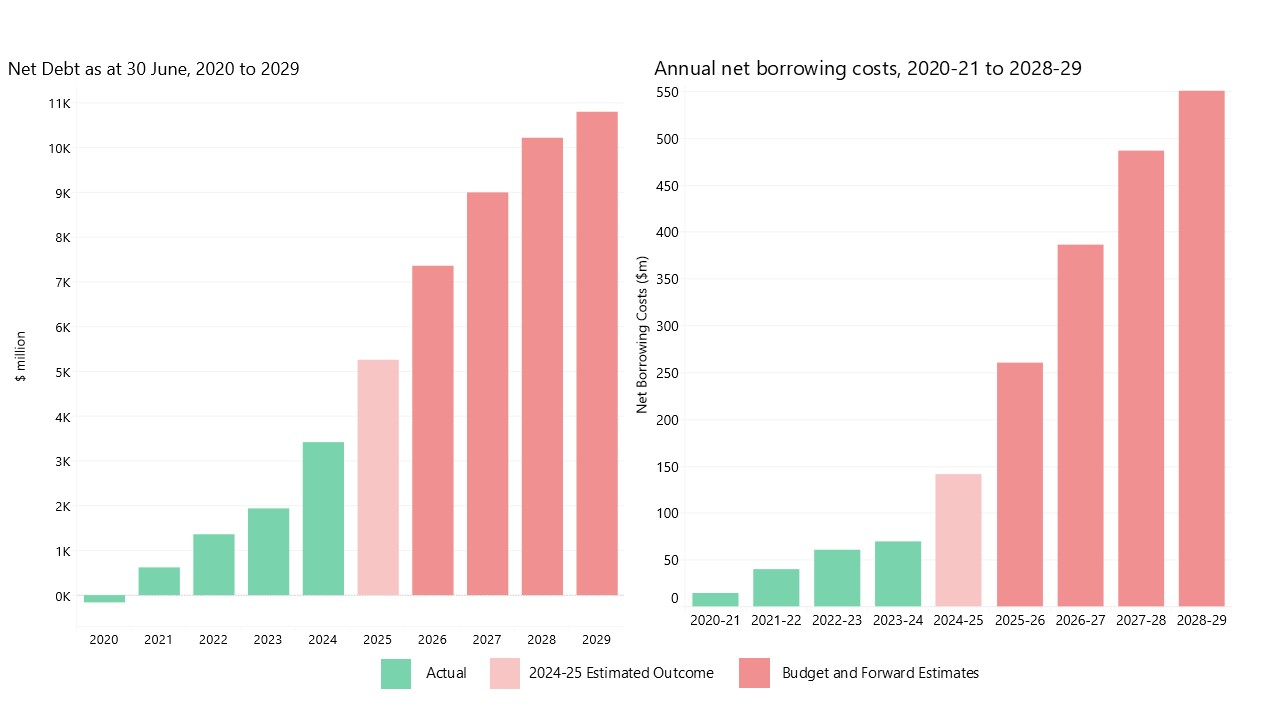

week’s Budget Papers show that Tasmania is living well beyond its means. Net debt is projected to reach $10.8 billion in four years. Annual interest payments alone are forecast to climb from $141 million this year to $550 million by 2028/29.

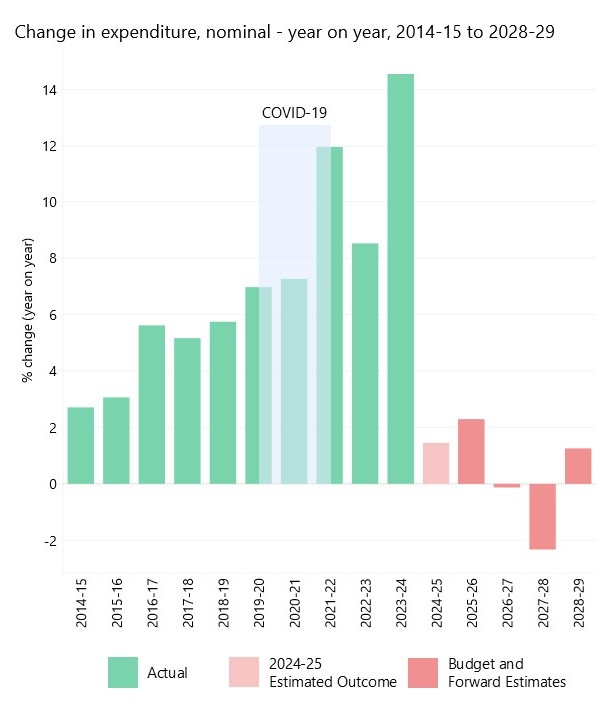

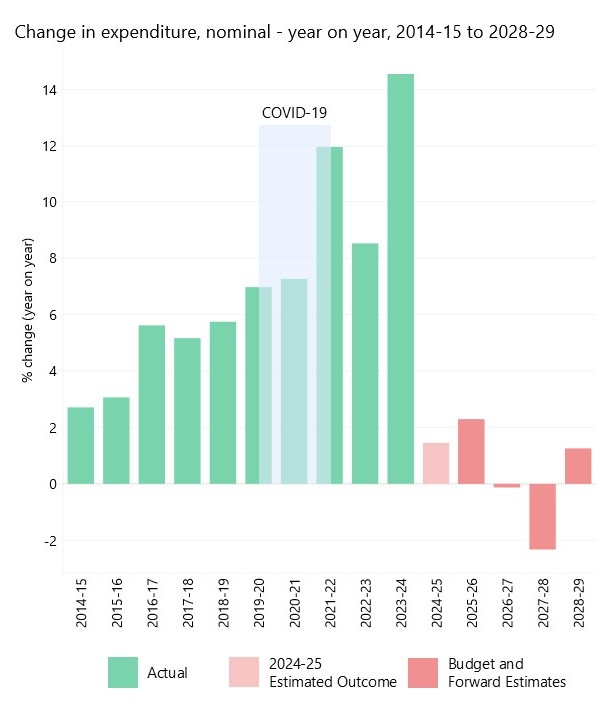

The Government’s plan, outlined in the Budget, was to effectively freeze spending over the next four years. While this may look plausible on paper, it means a cumulative spending cut of about 15% in real terms once we consider inflation and the rising cost of servicing debt. This is both unrealistic and largely unprecedented. As Eslake has pointed out, even the ‘tough’ post-global financial crisis budgets between 2010 to 2014 saw spending growth of 2.1%. The projected increase in spending across the next four years is 0.28%. Additionally,

Australian and

international evidence suggests that broad-brush ‘efficiency dividends’ or ‘hiring freezes’ are rarely effective or sustainable. Despite good intentions, trying to do the same thing in the same way with fewer resources almost never works.

Privatisation is another option that the Government was considering. It shouldn’t be ruled out on ideological grounds, but nor should it be seen as a solution to our long-term budget challenges.

For privatisation to help with the current fiscal situation, the one-off proceeds from selling a government-business would need to exceed the value of future tax and dividend returns from that business. And, even if there is a government business that meets these criteria, it won’t fix our structural challenges. Without broader reform, privatisation risks leaving Tasmania worse off over time.

It has been argued that economic growth and private investment would help with our budget woes. While both would be good for the state, Tasmania’s narrow tax base means they would only provide a small revenue boost.

State taxes only raise $1.82 billion (20.4% total state revenue) and of these, only payroll tax ($578.8 million) grows in line with the broader economy. This highlights the need for serious tax reform – and yet most of our political leaders have no appetite to even discuss the topic, let alone address it.

The idea that we can return to fiscal balance without significant reform doesn’t align with the current reality. So, the challenge for whoever forms the next Tasmanian government after this week’s political drama is clear. They will need to propose credible structural reforms that lead us back to financial sustainability, while also dealing with complex challenges in education, health, housing, and more.

Areas for reform

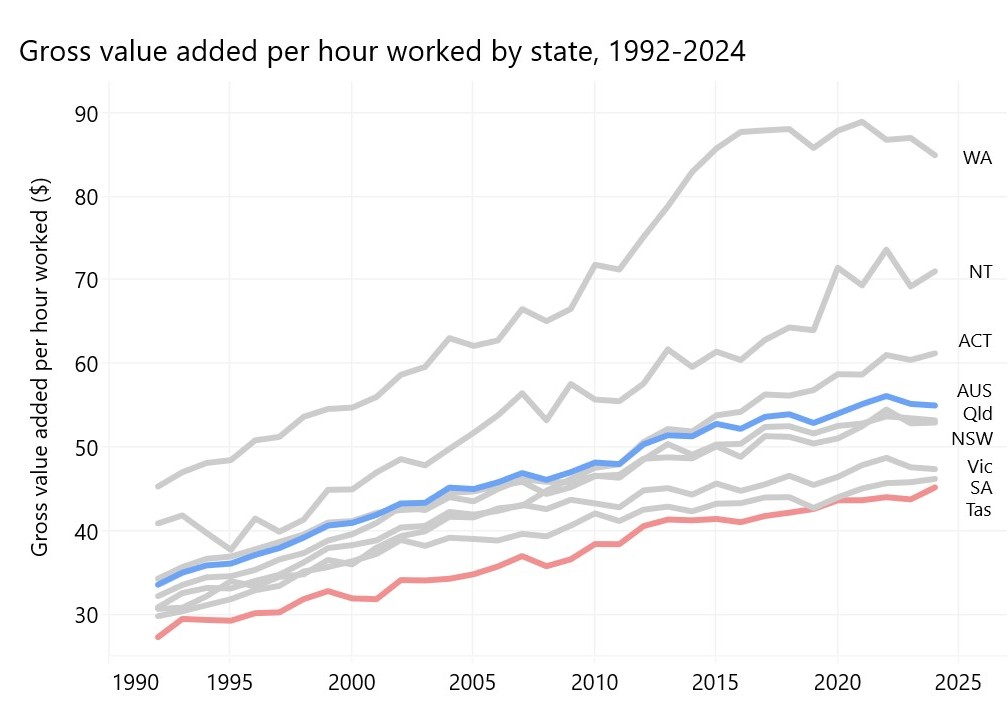

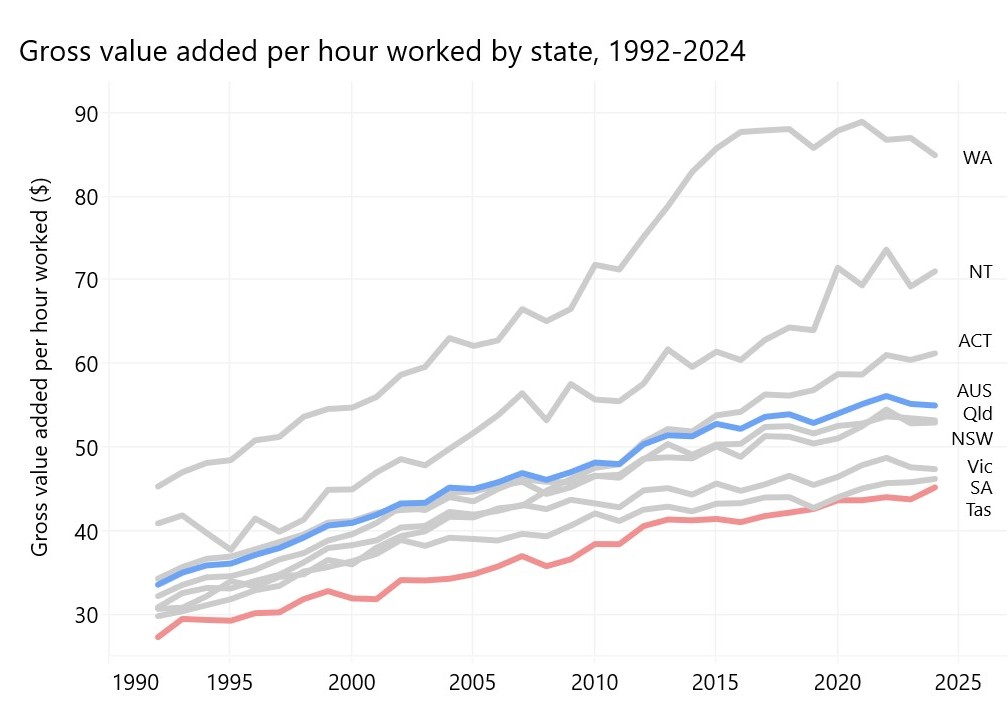

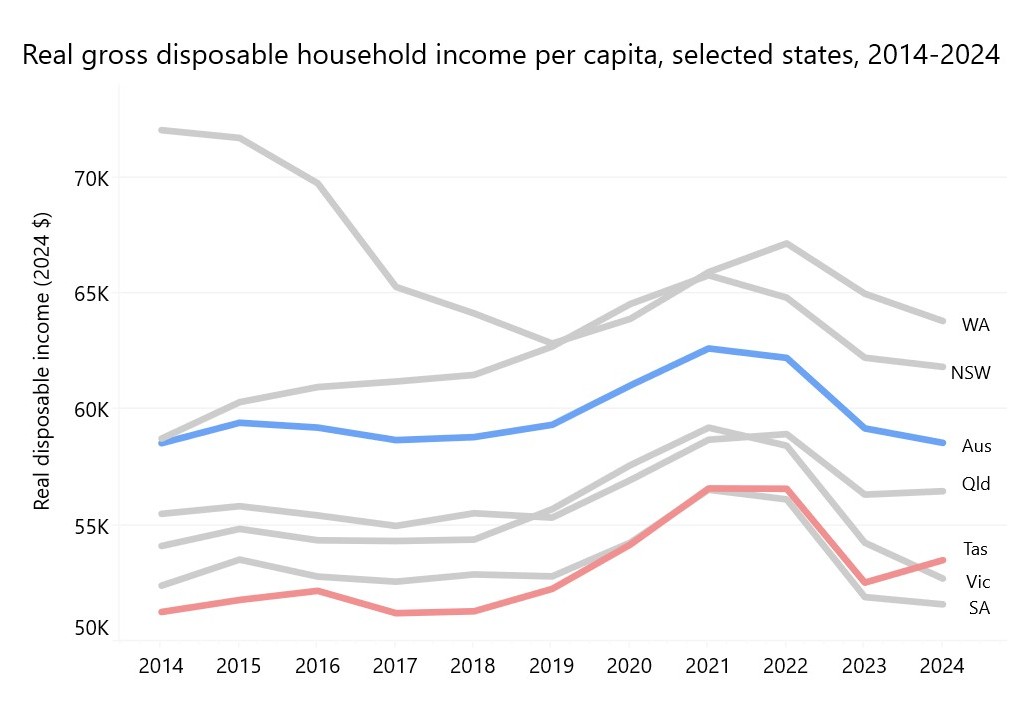

There has been a lot of talk about how productivity reform is vital for improving our standard of living. By traditional measures,

Tasmania’s long-term productivity performance has been among the worst in the nation – and the reasons are structural. Relative to the mainland, a high proportion of Tasmanians are employed in low-productivity industries. Our businesses tend to be smaller, and their productivity lags behind businesses in comparable industries elsewhere in Australia. This reflects factors including the scale of our economy, the lack of larger businesses, and a less-skilled workforce. One solution to this, is reframing our focus on productivity.

A narrow focus on productivity as an end in itself is unhelpful. It is important to think about workers, the environment, or community wellbeing as well. Fortunately, the productivity debate has evolved to consider broader measures of community wellbeing and sustainability. For example, a ‘quality-adjusted’

productivity measure in health might focus on long-term patient outcomes rather than just the unit cost of operations or medical procedures.

A key part of the puzzle is improving the effectiveness of the public service. Public sector reform rarely wins votes, but right now in Tassie it’s essential for ensuring that we have a public service that's capable, responsive, and future proof.

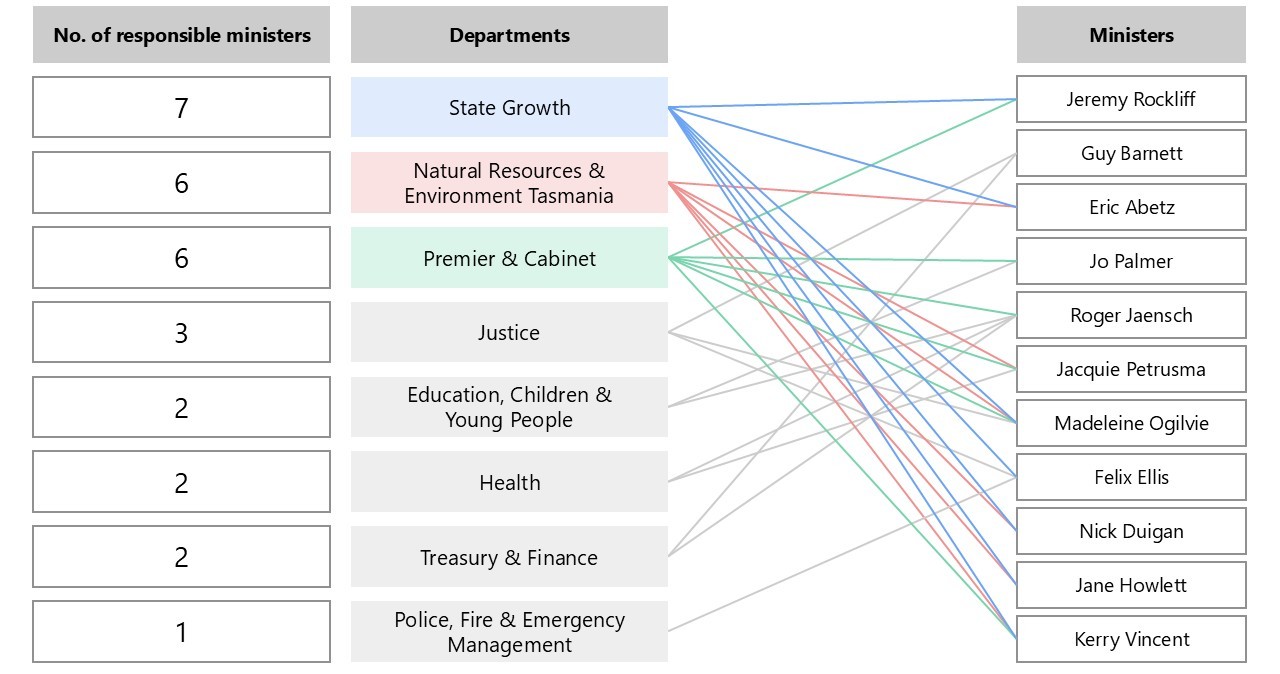

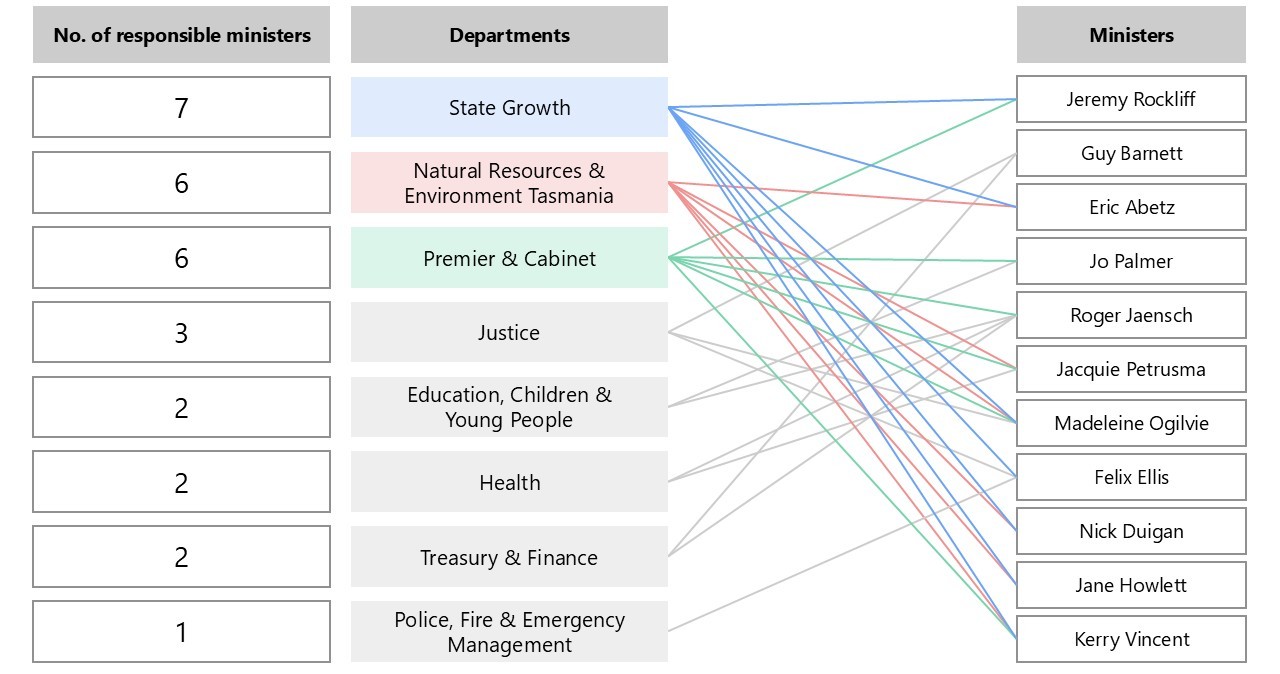

We could start by simplifying government structures. The relationship between ministerial portfolios and government agencies has been inconstant flux and is now too complex and fragmented. For example, the Department of State Growth now reports to seven different Ministers. The Department of Natural Resources and Environment reports to six. A public sector reform agenda also needs to include independent statutory authorities: a recent

Review of Homes Tasmania found that governance and reporting structures for statutory authorities could be streamlined to improve focus and accountability.

Relationship between Tasmanian Government Departments and Ministerial portfolios, May 2025.

Source:

Tasmanian State Budget 2025-26.

There are also many opportunities to improve the public sector’s technology, training, systems, management, and design. For example, many of the key recommendations of Dr Ian Watt’s 2021

Review of the Tasmanian State Service have not been implemented, including calls to improve capability, collaboration, and the use of technology. And, in an era of AI and digital transformation, many Tasmanian government systems remain paper based. Projects like the

10-Year Health Digitisation Strategy should be core priorities, if we are going to meet growing demand for health services with limited resources.

The future role of government in Tasmania

Perhaps most importantly, we need a broader, more honest conversation about the appropriate role and scope of state (and local) government in Tasmania. Key questions include:

- How and when should government support businesses and industry?

- How should governments plan and fund infrastructure that delivers public and private benefits?

- What public investments are needed to support a knowledge-based, future ready economy?

- Perhaps most challenging of all, how should government's determine which programs and projects we can no longer afford?

These will be difficult decisions. And they must be informed by a transparent, principles-based approach with a focus on our future needs and aspirations in a rapidly changing world.

Given our small size and limited resources, one solution the Tasmanian Government could advocate for is ‘collaborative federalism’. The aim of collaborative federalism is to ensure that Commonwealth spending is informed by local insights and aligns with community needs. It could also involve new strategic partnerships with the Commonwealth and other states to share systems, data, and expertise. This would save money and avoid duplication. The recently re-elected Albanese government provides an important opportunity to leverage Labor’s strong federal vote in Tasmania.

The Tasmanian Government will continue to play a big role in delivering essential services. But with growing demand and limited resources, we need to do more to target support to those in need. And at the same time, there’s a case for asking Tasmanians with greater capacity to contribute more. That might mean rethinking concession models and universal service provision – and being honest about what’s financially sustainable in the long term. Ambitious reforms like this won’t be easy (or popular) but if we’re serious about equity and sustainability, they can’t be avoided.

Gender budgeting is one example of how smarter government isn’t just about cost… It’s about who benefits, who’s left out, and how we measure success. This year’s

Gender Budget Statement didn’t receive much attention, but it offers some insight into what’s improving and where we’re still falling short.

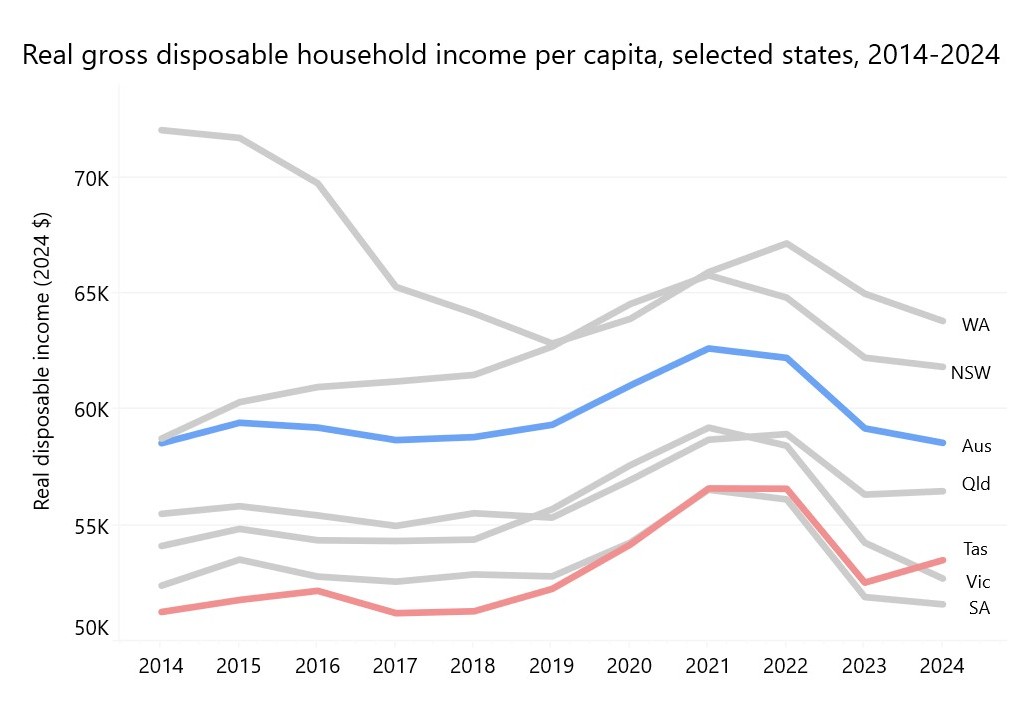

While Tasmania’s gender pay gap has consistently been

the lowest in the country, with the gap now at 5.2%, this mostly reflects lower wages across the board – Tasmanian women still earn less than the average Australian woman. And underemployment continues to be a major issue, with many women unable to secure the hours they need to achieve financial security.

These aren’t fringe issues. A budget that works for Tasmania needs to work for all Tasmanians. And that means embedding equity considerations into every stage of policy design and delivery, not just headline measures.

Where to from here?

The events of the past year (and the past week) have made one thing clear: we’re at a moment of choice. We need fundamental change. And that means setting new priorities, rebuilding trust in government, and reimagining the way we do politics on this island. We need to be realistic about what we can afford, and ambitious about what we want to achieve.

Our future depends on it.