Despite Tasmania’s strong position, decarbonisation will not be easy. As our emissions-intensive industries come under increasing financial, regulatory, and social pressure to clean up their act, the communities that rely on them will experience major changes. Expanding renewable generation and transmission while building up new, green industries also brings complex challenges – from workforce and housing shortages to legitimate community concerns about impacts on local biodiversity, agriculture and visual amenity.

Managing these challenges, and fully realising the social, economic, and environmental opportunities of decarbonisation, requires careful planning and lots of

community involvement. In this PIMBY, we argue that Tasmania needs a statewide ‘just transition framework’ to guide the development of place-based transition plans across our three major regions. This approach could position Tassie as a world-leading example of equitable, community-led decarbonisation that generates employment, investment, innovation, and wellbeing benefits for all Tasmanians.

A just transition framework - from ambition to action

We use the term ‘just transition framework’ to describe a practical set of guidelines that help regions, industries, or organisations to develop their own decarbonisation plans. Rather than focusing on a single pathway or particular projects, a just transition framework provides shared principles, priorities, and areas of focus - a 'just' transition for all. This approach allows different places to develop plans that reflect their own circumstances, strengths, and challenges. Several countries and international organisations have developed their own just transition frameworks.

One example is Scotland’s

National Just Transition Planning Framework – the first of its kind at a national level. It’s designed to help industries, regions, and organisations develop their own ‘Just Transition Plans’, which set out how emissions will be reduced while also managing the social and economic impacts of that change.

Closer to home, the Regional Australia Institute (RAI) worked with Transition & Recovery Australia to develop the

Transition Framework. This identifies seven areas that can be used to assess community readiness for transition and evaluate existing transition initiatives. It is designed to support place-based approaches in regional Australia, recognising that different regions will experience the transition in different ways.

Planning for change, together

Decarbonisation will have huge and varied impacts across Tasmania. Some communities will gain new investment and employment opportunities, but others may face disruption as industries change, infrastructure is built, and land use shifts. A state-wide just transition framework would help Tasmania maximise social, economic, and environmental benefits, while mitigating inevitable challenges.

We should look to other jurisdictions to understand best practice, but any such framework must be designed

by and

for Tasmanians. It also

needs to build on existing policies, initiatives, and assets – such as the forthcoming

Tasmanian Sustainability Strategy and the recently released

20-year Preventive Health Strategy – rather than duplicating or overriding them. This includes recognising Tassie’s unique blend of

To fully harness the transition's potential, regional communities want practical and accessible transition advice, rather than high level targets and strategic ambitions.

Regional Australia Institute, 2024

environmental, cultural, demographic, and economic factors. Taking this approach would help ensure that our decarbonisation planning is grounded in local realities, increasing the likelihood that our transition will be sustainable and equitable, ultimately leading to a more resilient, prosperous, and genuinely ‘

Climate Positive’ future.

Getting the just transition scale right

The catch is, transition planning needs to happen at a scale that balances local relevance with capacity and capability. If it’s too broad scale, it risks overlooking local conditions and community priorities. If it’s too narrow, it could overwhelm local organisations and fragment decision-making.

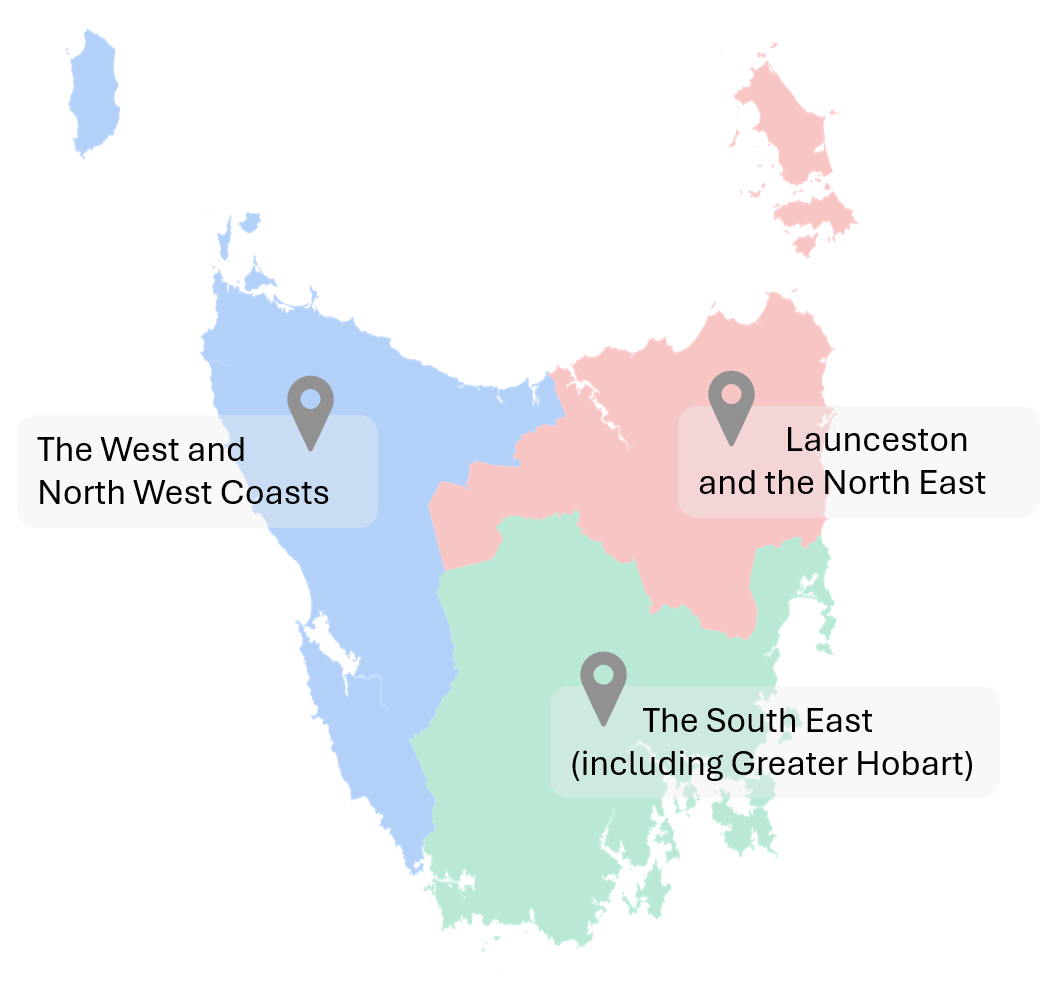

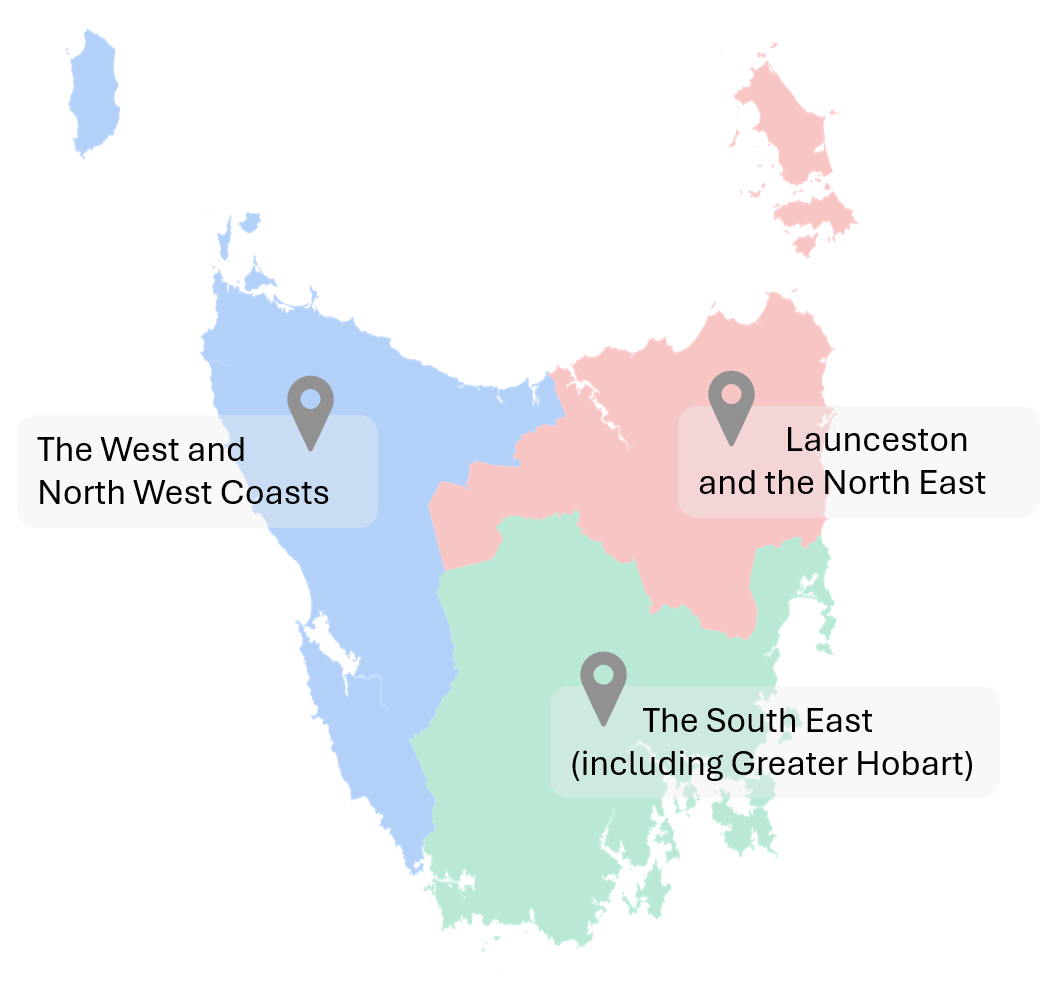

In Tasmania, we think that just transition planning should be guided by a state-wide framework but developed at the level of our three major regions:

- The South East (including Greater Hobart)

- Launceston and the North East

- The West and North West Coasts

These reflect the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ SA4 areas, although we have combined Greater Hobart and the South East to recognise the strong economic, social, and employment connections between them. We believe this regional scale strikes the right balance for three main reasons:

- It creates opportunities for a place-based approach (PBA) to planning: PBAs are acknowledged as effective for tackling complex regional policy issues because they focus on institutional, social, cultural, economic, and political contexts, and draw on local knowledge to solve problems.

- It aligns with existing geographies and jurisdictions: These chosen regions align with established groupings of local governments and their peak bodies, as well as natural resource management (NRM) committee areas. They also follow the geographies used by the Tasmanian Government in policy areas like planning, healthcare, infrastructure, and strategic land-use.

- It reflects functional economic areas and associated industrial facilities: This means that decarbonisation impacts (such as changes to employment, infrastructure, and land use) are more likely to be experienced within the same regions where people live and work.

Planning at the level of these three regions offers the best combination of resourcing, capability, and devolved decision making, while still allowing for a consistent, statewide approach.

The building blocks of a just transition framework

At minimum, a Tasmanian just transition framework needs to do two things. First, it would establish a set of guiding principles to shape how transition planning is done. Second, it would define a set of ‘domains’ that outline the scope of what regional plans should consider.

These two things support a better approach to decarbonisation – one that recognises climate change as not just an environmental or technical problem, but a social, economic, and environmental one that impacts every part of Tasmanian life.

Principles

To make sure that regional just transition plans are consistent in approach and emphasis, we’ve developed five guiding principles. These are based on a review of similar frameworks, adapted to fit Tasmania’s particular context and priorities.

Recognise the urgency of zero emissions

Tasmanian communities are already suffering the effects of the

climate emergency. Transition planning must be grounded in the urgency of reducing emissions as quickly as possible, in line with national targets and global efforts to limit further warming.

Ensure inclusivity and accountability

Just transition plans should be

co-designed with diverse stakeholders and social groups through meaningful engagement and dialogue. They also need

robust, transparent, community-led governance. Inclusivity and accountability is essential to build trust and make sure that those most affected by change are involved in shaping decisions.

Harness change to address social and economic inequalities

Decarbonisation offers a unique opportunity for Tasmania to address its current position as Australia’s poorest, least educated, and least healthy state. Realising this potential requires careful planning that focuses on reducing existing inequalities, and preventing new inequalities from emerging.

Use the best available evidence

Transition planning in Tasmania should draw on high-quality, independent evidence. This includes drawing on local data, context-specific scenario analysis, and lessons from what has worked elsewhere.

Prepare for unintended consequences and trade-offs

Decarbonisation is a complex, non-linear process involving multiple sectors, types of actors, places, and levels of government. Transition planning must recognise that trade-offs are inevitable, and that decisions in one area can have unintended consequences elsewhere. Creating space for the Tasmanian community to discuss these trade-offs and agree to reasonable compromises is essential.

Domains

Just transition planning needs to be broad in scope if it is to deliver lasting equitable outcomes. To this end, some researchers argue for

a whole-of-systems approach which recognises that there isn’t “one transition but rather multiple, interdependent transition processes that rarely follow linear trajectories”. Drawing on international best practice, we propose that Tasmania’s transition planning should cover seven main domains.

Energy

Energy sits at the centre of Tasmania’s transition effort. More than half of the energy used across the state – including in

transport and industry – still comes from fossil fuels. Without serious investment in new wind and solar generation, upgraded transmission, and fossil fuel replacements, Tasmania will struggle to decarbonise and future-proof our industries.

Health and Wellbeing

Effective transition planning needs to prepare for potential impacts on health and wellbeing in the state. For example, using FIFO workers for large energy projects may increase the pressure on regional health services, while the emergence of new industries could revitalise community identity.

Housing and Infrastructure

Tasmania’s existing challenges in this area will be intensified by climate change. Transition planning needs to cover reducing emissions from construction and supply chains, incorporating climate resilience into planning processes and construction standards, and anticipating the impact of new renewable energy projects on local housing markets.

Employment and Industry

A just transition will create new jobs and industries, while also changing or reducing employment in emissions-intensive sectors. Planning should focus on ensuring Tasmanians have access to the skills, training, and pathways needed to participate in emerging industries, and that the benefits of economic change are widely shared.

Tasmanian Aboriginal Community

Meaningful involvement of the Palawa, the First Peoples of Lutruwita/Tasmania, is essential to a just transition process. Tasmanian Aboriginal nations have stewarded this land for many generations, and hold deep knowledge that can strengthen transition planning and outcomes. The transition also presents opportunities to address long-standing social and economic inequalities experienced by Tasmanian Aboriginal people.

Education

A strong education system is vital for an effective and fair transition. Planning should cover the research, skills and training that Tasmanians need to thrive in a low-emissions world, with particular emphasis on reskilling pathways for workers in emissions-intensive industries.

Natural Environment

Tasmania’s natural environment is one of its most valuable assets. Just transition planning would support environmental health by reducing pollution and mitigating biodiversity loss due to climatic changes. However, rapid decarbonisation and environmental protection sometimes clash. The ‘green-versus-green dilemma’ needs to be addressed through effective regulation and community consultation.

As we have been exploring through

Tamar Valley Zero, these domains are not mutually exclusive. They interconnect, overlap, and cut across the responsibilities of all levels of government. This only reinforces the value of PBAs for transition planning – responding to local context while addressing system-wide change.

Making the just transition work

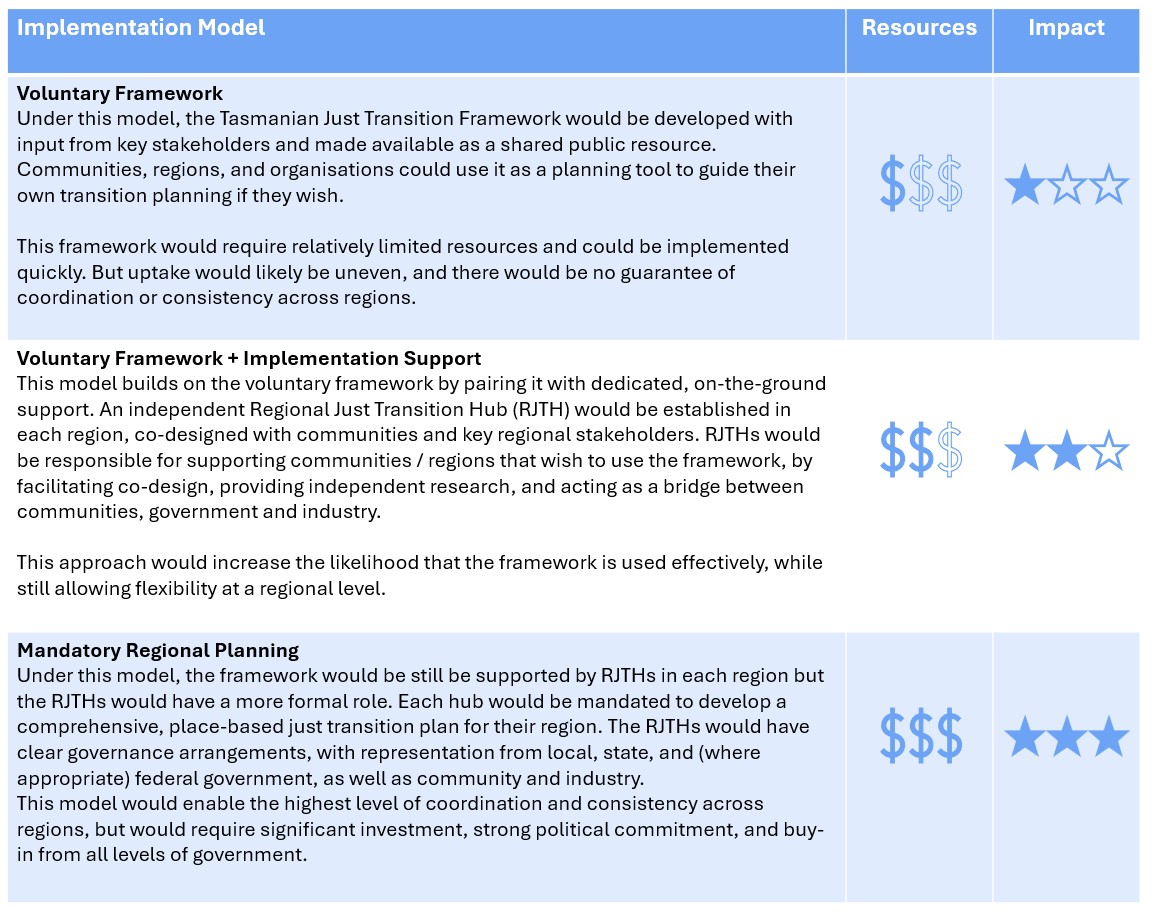

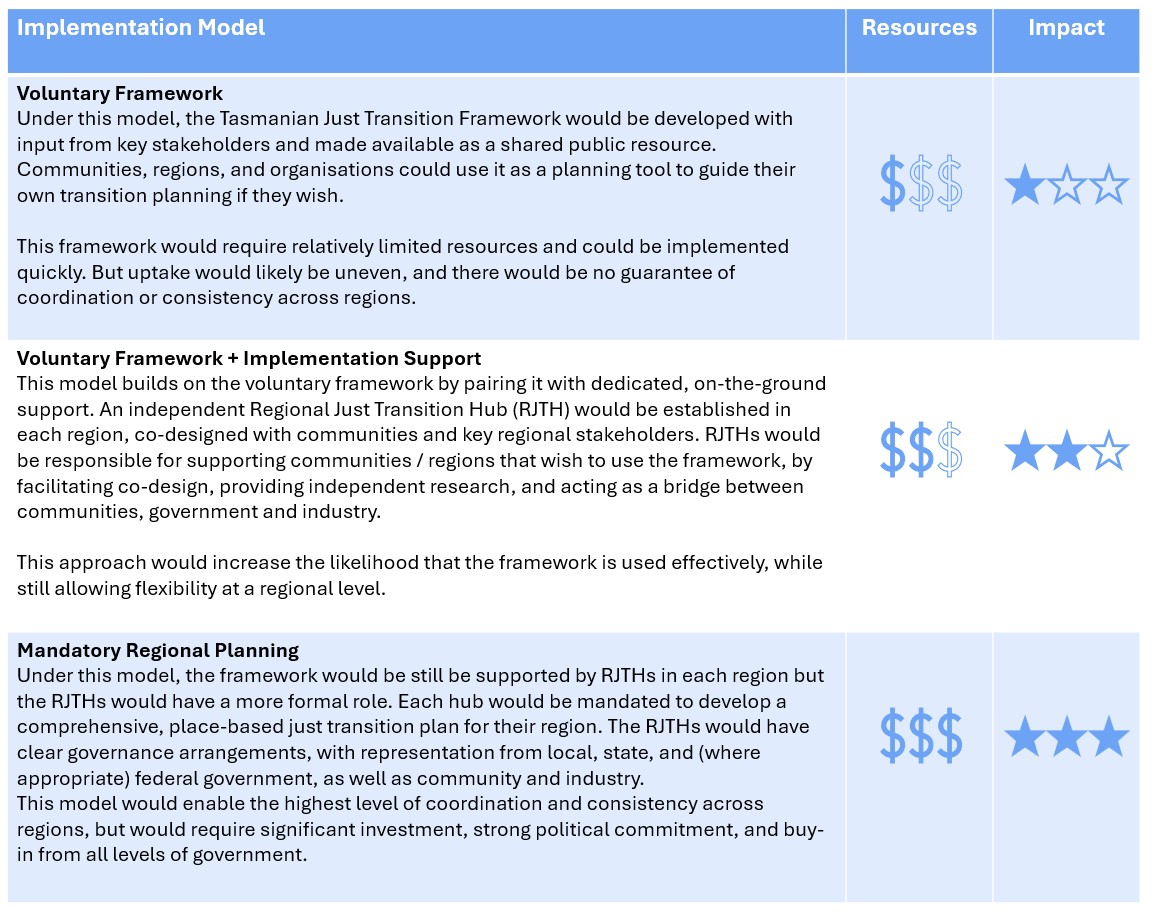

There are several ways a Tasmanian framework could be implemented. In our view, there are three promising models. These options differ in terms of resourcing, governance, and the level of coordination they require, but each builds on the same framework.

A plan that lasts

Decarbonisation will reshape Tasmania’s communities, economy, and environment over the coming decades. Although the transition is needed, it will involve difficult choices, uneven impacts, and significant investment. Whether the transition delivers lasting social, economic, and environmental benefits will depend on how it’s planned, and how meaningfully communities are involved.

A just transition framework, paired with place-based regional planning, offers a practical way to bridge the gap between high-level climate ambition and real-world decision-making. A just transition plan makes the work a little easier by giving us shared principles and a common structure, while still leaving room for local priorities and leadership.

Sometimes it’s easy to think that climate change is too big a problem, and that adapting to it is beyond us. But if we take a whole-of-system approach in ways that look beyond individual projects or sectors, decarbonisation can work for place

and people. The TPE will be aiming to ramp up our work in this area in 2026, building on our

Tamar Valley Zero pilot project.

A Tasmanian just transition framework could be what we need to deliver climate action that's locally grounded, widely supported, and built to last.