We also have our own approach in Tasmania. The Equal Means Equal strategy focuses on cultural change, empowerment, and visibility. These national and state strategies might provide a roadmap for change, but what does gender equality actually look like in Tasmania and the rest of the country? In this article, the women of TPE take a closer look at gender equality – or inequality as it were – in Tasmania. We use the 5 priorities established in the national strategy, looking at where we stand and where we need to go next.

Ending gender-based violence

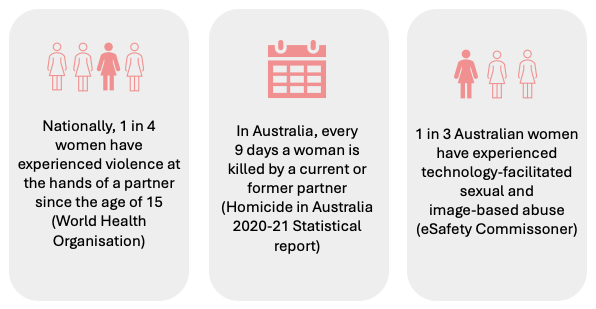

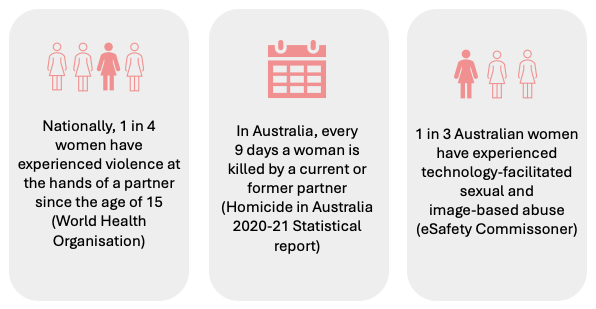

Let’s start with an issue that is at epidemic proportions in Australia and across the world: gender-based violence. Violence against women and girls is both a major public health concern and a violation of women’s human rights. The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that

one in three women worldwide have experienced either physical or sexual violence in their lifetime. The problem looks very similar at a national level in Australia –

one in four women has experienced violence at the hands of a partner since the age of 15.

In Tasmania, the situation is concerning too.

Recent research reveals an alarming picture: 40% of Tasmanian teenagers have experienced domestic violence in their relationships and young Tasmanian women are twice as likely to experience abuse compared to their peers in Australia. This research shows:

- Nearly all cases involved a male-identifying abusive partner and a female-identifying victim-survivor

- Some relationships had significant age gaps (8-22 years), creating serious power imbalances

- Many victim-survivors were under 16 years old when the relationship started, making them especially vulnerable

- Financial abuse is common and a major factor in women's homelessness in Tasmania

- Many young Tasmanians don't recognise the warning signs of relationship abuse because healthy relationships aren't taught in schools

As of 2022, women in Tasmania were

more likely to experience violence than women in the rest of Australia:

- 43% of Tasmanian women had experienced physical or sexual violence since the age of 15 – higher than the national average of 39%

- Sexual violence was more common in Tasmania (26%) than nationally (22%)

- More than half of Tasmanian women (57%) had experienced sexual harrassment, compared to the national average of 53%

These numbers make one thing clear: violence isn’t just a women’s issue – it affects the entire Tasmanian community. The fact that Tasmanian women face higher rates of violence than the national average points to a dire need for a community-wide response. Awareness of gender-based violence may have grown through national and state efforts. But the reality remains that, despite this progress, real change has been very slow... And therefore that harm continues at a concerning rate.

Unpaid and paid care

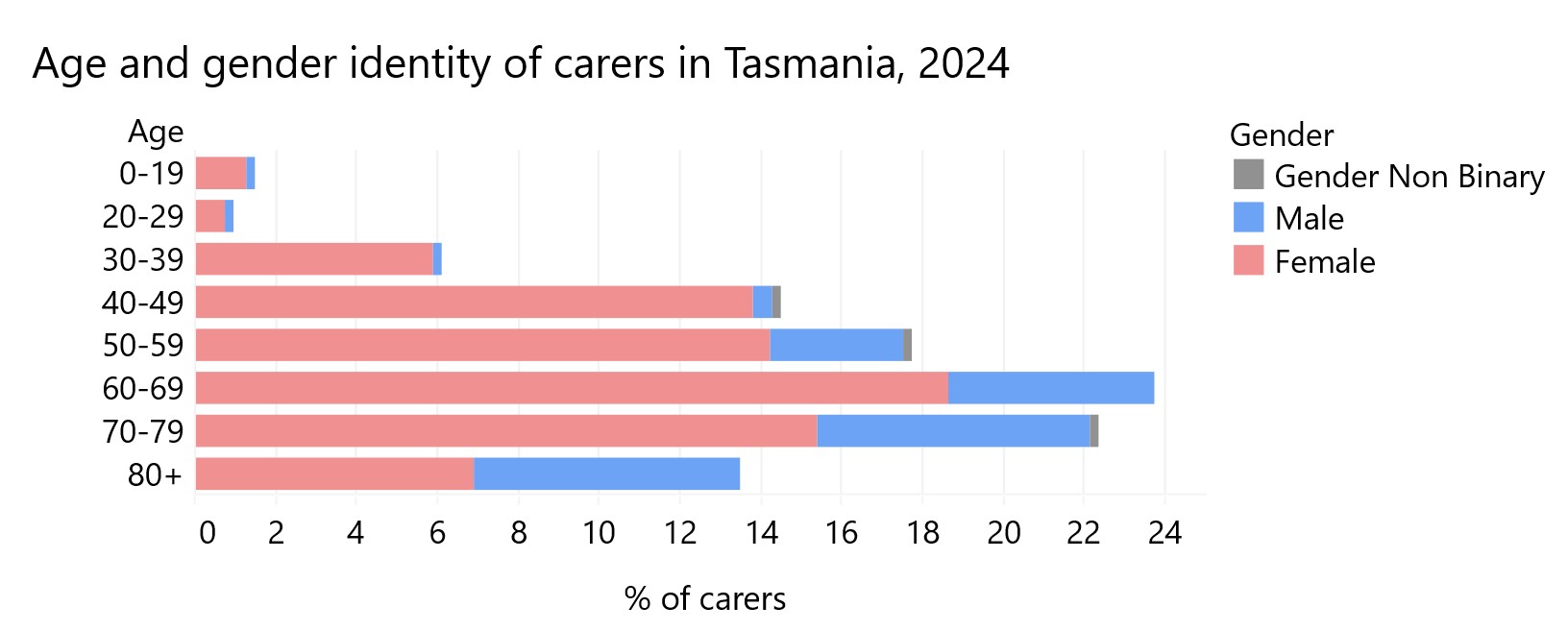

Women in Australia continue to carry the overwhelming burden of unpaid care work – whether through childcare, eldercare, or household responsibilities.

Equal Means Equal acknowledges this imbalance and suggests that the answer in Tasmania is support for flexible work, affordable childcare, and recognition of unpaid carers. Nationally, women undertake

an average of 32 hours of unpaid work and care each week – 9 hours more than men. This extra workload isn’t simply an inconvenience. Unpaid labour affects women’s ability to participate fully in the workforce and achieve financial independence.

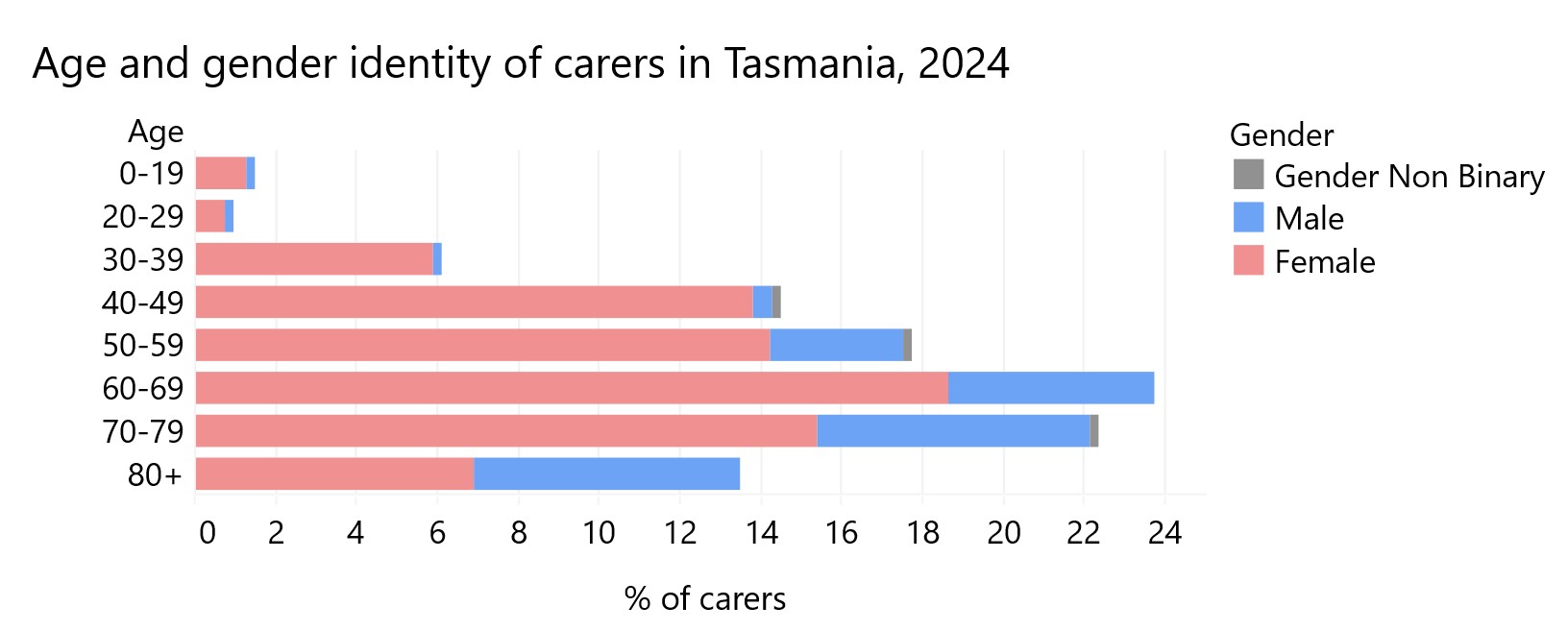

The above chart shows that in Tasmania, the imbalance is particularly striking when women are in their 30s and 40s, when career progression is often most critical. Meanwhile, men only take on more unpaid care work once they're at an age where their careers are well-established, or after retirement.

But one of the biggest challenges in addressing this issue is that it isn’t measured well. Unlike paid work,

unpaid care often goes untracked or undervalued in statistics. If we don’t measure it, we don’t treasure it. The lack of data around unpaid care makes it easier to overlook the impact it has on Tasmanian women – despite how care work is essential in keeping families, workplaces, and the entire economy running.

Women don’t just take on more unpaid care work – more women than men work in the paid care sector. Unlike male-dominated industries, care jobs often come with lower pay and fewer protections, including casual work arrangements and the need to change employers often. This means that many care workers miss out on benefits like long service leave.

One solution to this inequality is the introduction of

portable long service leave entitlements, which can compensate workers (especially women) who have spent years in the care economy but lack financial security later in life. The challenge? It requires strong government commitment and buy-in from employers. The good news?

Victoria has already expanded its long service leave scheme to cover community workers and contract cleaners, both female-dominated industries. So,

it is possible to make change happen.

Economic equality and security

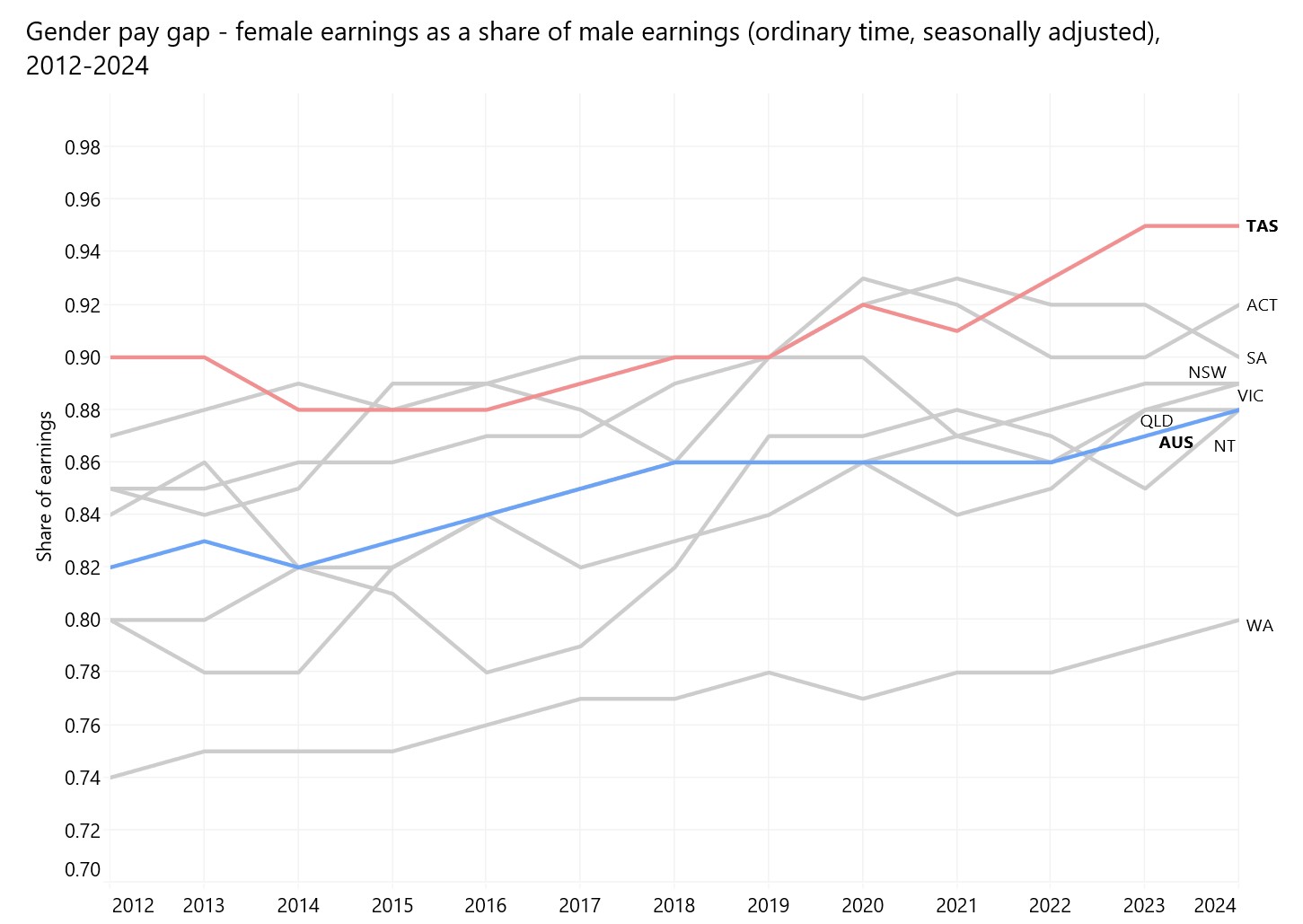

Over the past decade, women’s weekly earnings have gradually improved, but in Australia

100% of occupations still have a gender pay gap in favour of men.

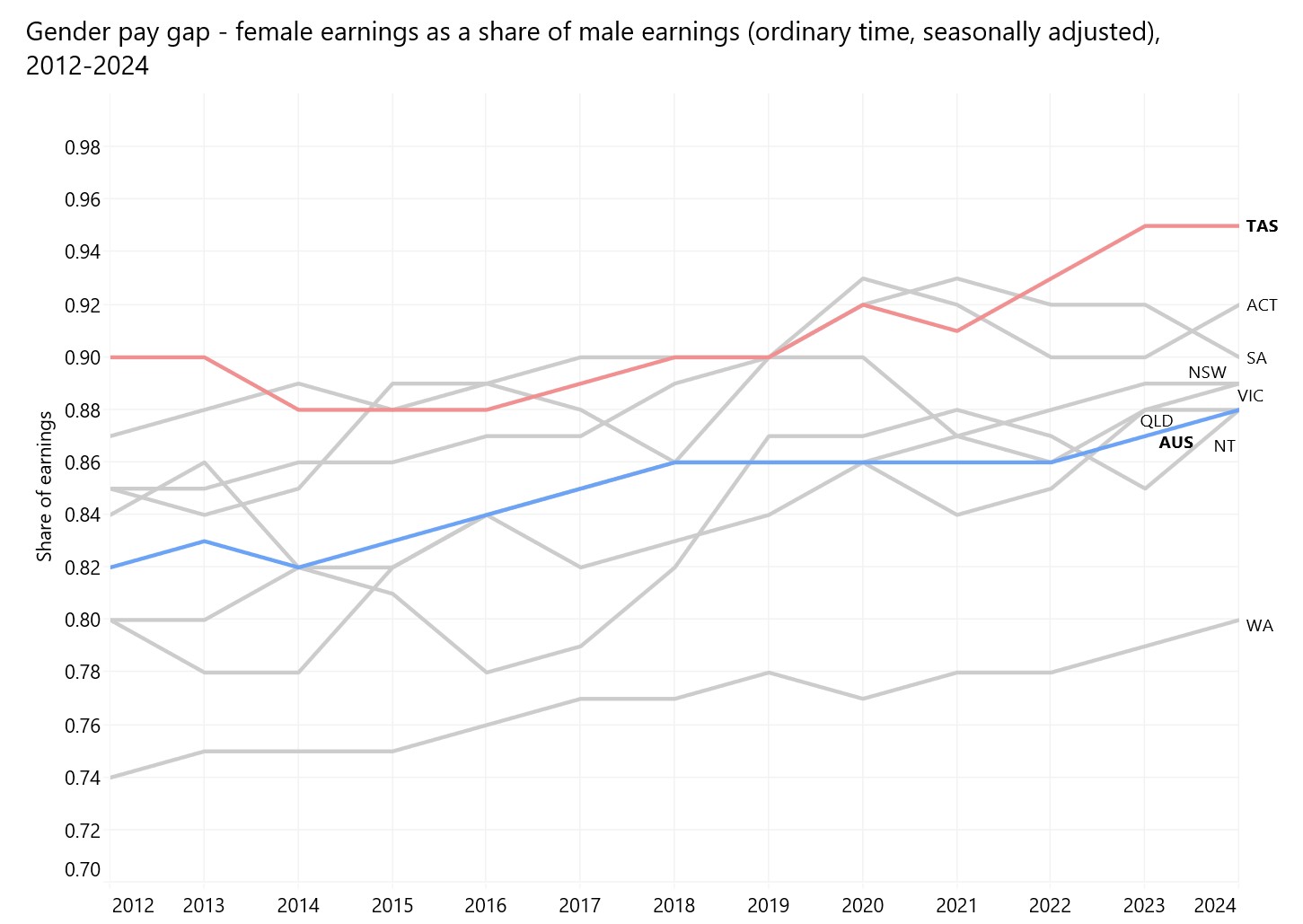

Tasmania is doing better than most. We have a smaller gender pay gap than the national average, and women’s earnings have grown steadily over the past 10 years. As of 2024, women in Tasmania earn 95 cents for every dollar earned by men – the highest ratio in the country and up from 90 cents in 2012. In contrast,

women in Western Australia still earn 20% less than men – largely because of the prevalence of high-paying, male-dominated industries such as mining.

South Australia and the Australian Capital Territory are also higher than the national average, whereas New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland and Northern Territory closely align with the national average of 89%. The good news is that most states have made real progress in closing the gender pay gap over the past decade.

You might wonder why Tasmania is leading the way. The answer probably lies in industry composition. More women in Tasmania work in public sector jobs like healthcare (73% of workers are female) and public administration (53% female).

Stronger union representation along with reforms to the Fair Work Act have also helped women negotiate better wages.

As of January 2025, the female labour participation rate in all industries in Tasmania closely aligned with national rates of participation (

89% and 88.8% respectively). This is a 6% increase since 2012. Despite this progress, the persistent gap in workforce participation highlights ongoing gender disparities in employment opportunities and the need for economic inclusion in Tasmania.

But it’s important to remember that these statistics don’t tell the whole story. Tasmanian

women experience higher rates of under-employment than men. Closing the gender pay gap isn’t just about salaries because under-employment means that even those with jobs often struggle to get the hours they need to achieve financial security.

The bottom line is that the national trend is heading in the right direction, but progress isn’t happening evenly across the country. Tassie’s (relatively) low pay gap proves that wage equality isn’t just about gender – it’s also about industry and equitable wage structures.

Health

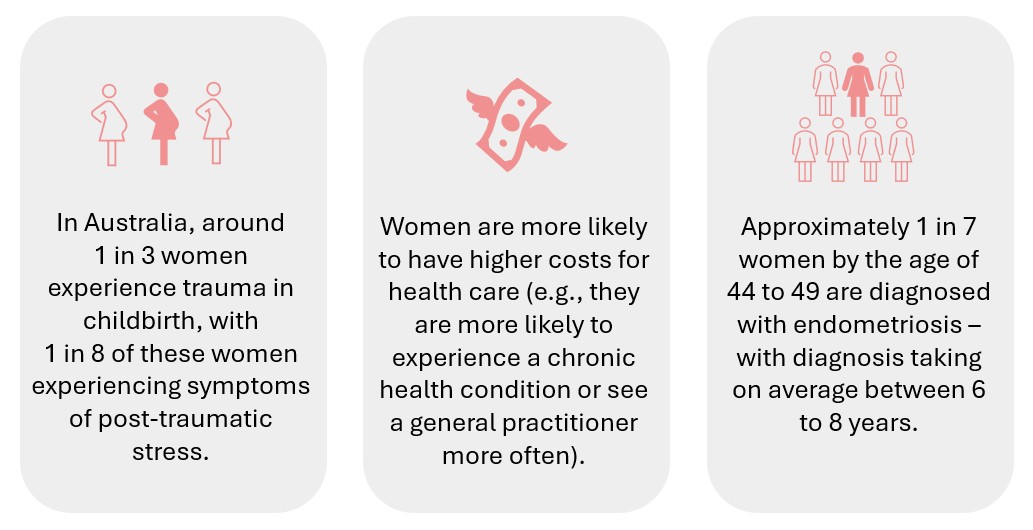

Women’s health is connected to economic equality, safety, and access to services.

A

recent national survey found that two out of three women report experiencing bias and discrimination in healthcare. And, 80% of caregivers said a female person they cared for had faced similar treatment. When this sort of discrimination happens, it has huge impacts. Many women report ‘near misses’, where dismissed health concerns turned out to be life-threatening, along with significant financial strain and lost career or educational opportunities.

The story is not much different in Tasmania. Women's Health Tasmania reports widespread and systematic issues for women's health in Tassie:

Women’s Health Tasmania suggests this reflects low levels of reproductive health literacy in the health workforce.

Globally, maternal mortality (deaths related to pregnancy or following birth) is a widespread problem. The World Health Organisation (WHO) reports that

a maternal death occurred almost every two minutes in 2020. Fortunately, these

numbers are not nearly as dire in Australia, but the WHO suggests that care from skilled health professionals before, during, and after childbirth is the key. The

recent closure of the private maternity ward in the Royal Hobart Hospital points to ongoing inequality in our medical and health systems.

At the end of the day, the issue is inequality in healthcare access. Not all Tasmanians receive the same standard of care, and many Tasmanian women currently face a lack of safety, choice, and inclusion in health services.

Leadership, representation, and decision-making

In the political arena, Australia is making strides. The federal cabinet is nearly gender-equal, with 11 women out of 23 ministers (~48%). The Tasmanian Parliament is doing slightly better,

with 52% of representatives being women. This makes us the state with the highest rate of female representation in Australia.

In local government, this trend continues with

more female than male Mayors (55% female), and Deputy Mayors (59%) in 2024. However, females only make up 40% of councillors across Tasmania’s local councils. Equal representation in local government is important in itself and provides

an important pathway into state and federal politics. So, when women are missing from local government, it may reduce their chances of progressing to state and national leadership. This contributes to long-term gender imbalances in power and decision-making.

Men still far outweigh the number of women in local government CEO/General Manager roles: in our 29 local councils,

only four GMs are women. While the community is voting in good numbers of women, there is still gender bias present in the selection for managerial roles. This may reflect more structural issues, as a lack of pathways and support for women in local government administration means they are less likely to access opportunities to enter management roles.

Women in politics also face unique challenges. Many report

burnout from balancing responsibilities,

verbal abuse at work and online, and public scrutiny at far higher rates than male counterparts. In a

2022 survey of those working in Tasmanian ministerial and parliamentary support roles, including Members of Parliament, 15% reported that they had experienced sexual harassment at work. Experiences such as these reinforce the cycle of underrepresentation.

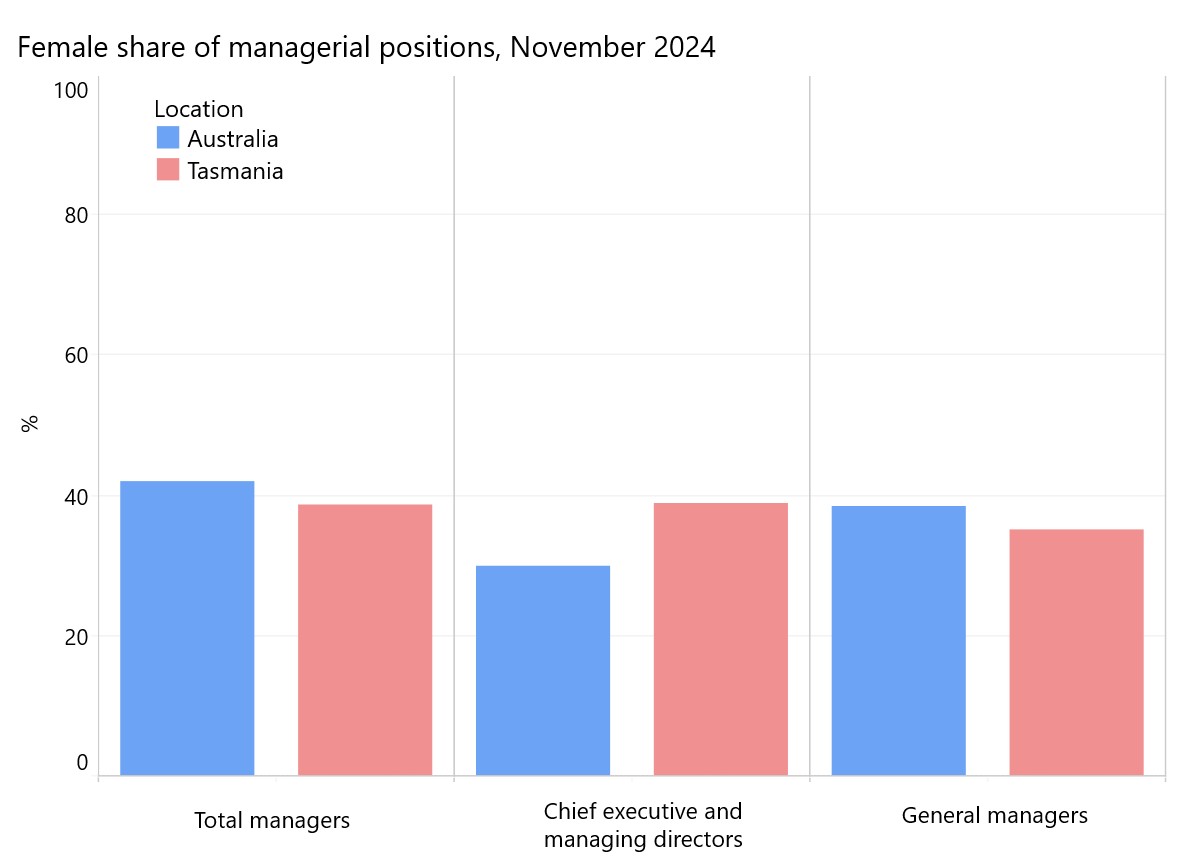

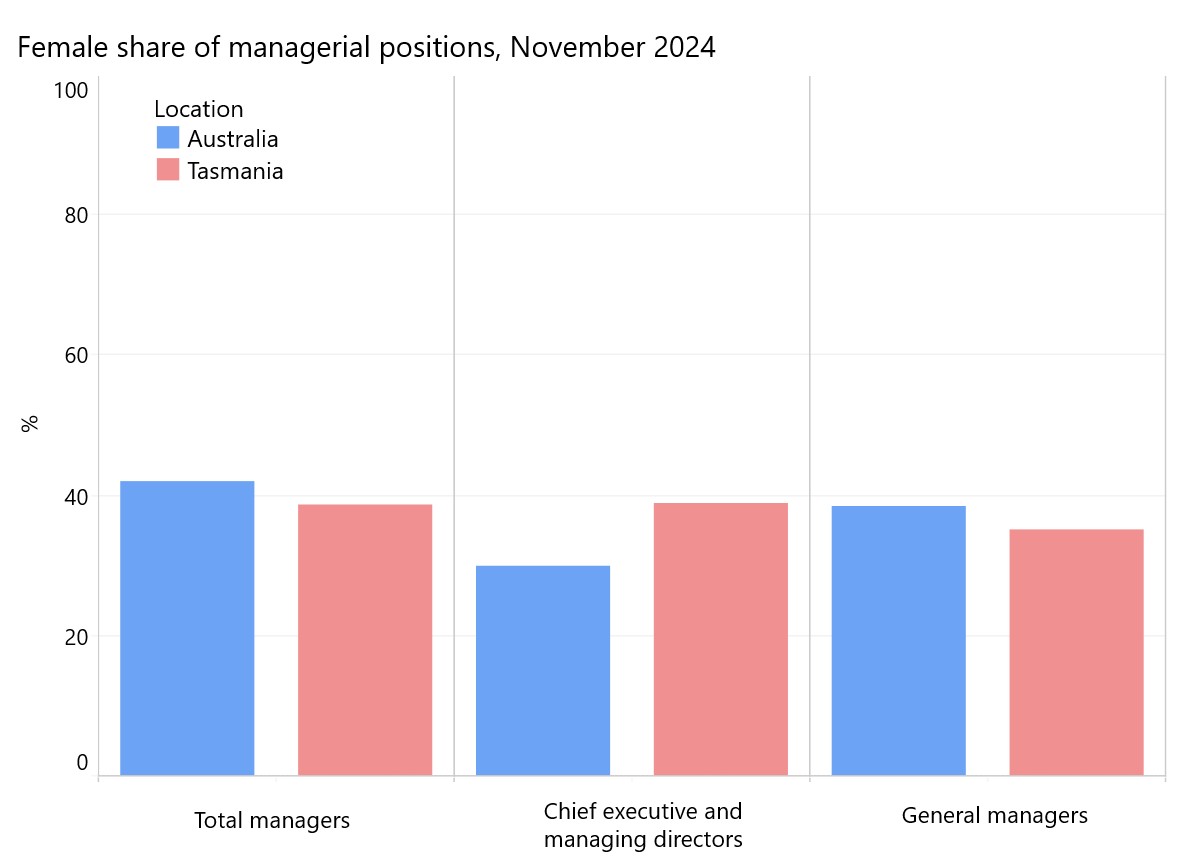

While there is some good news for women in politics, data on women’s representation in leadership shows there is still very much a glass ceiling in Australia. As of 2024, women held 21.9% of CEO positions and 35.1% of key management roles. Tasmania is slightly ahead of the national average for female chief executives and managing directors, but men still dominate other top business roles.

Leadership shapes decision-making at the highest levels – from workplace policies to economic strategies. When women are underrepresented here, their voices and perspectives are missing from decisions that impact them.

It’s great to see progress in leadership, but we need to do more than celebrate representation across our parliaments. We need to close the gap in local government management as well as the private sector, and create pathways for more women to lead at every level. Programs like the

UTAS Pathways to Politics for Women aim to increase the number of women entering the political arena by providing training, mentoring and support to embrace their political ambitions.

Marching forward

The theme of International Women’s Day 2025 is “Marching Forward: For ALL Women and Girls”. It’s a reminder that progress doesn’t happen on its own, or by making promises – we have to push for it. And before anyone asks, yes there is an International Men’s Day – it’s November 19 (and while inequality continues, every other day too!).

Have we turned promises into progress?

In some ways, yes. We are seeing some improvement when it comes to awareness around gender equality issues.

Australians are increasingly rejecting problematic beliefs about gender equality. For example,

a national survey on attitudes towards violence found that in 2013, just over half of people (54%) agreed that controlling a partner’s money was a form of domestic violence. By 2017, this had increased to 66%, and by 2021, 81% of people recognised this as domestic violence.

But awareness isn’t enough. If we want real gender equality in Tasmania and Australia, we need action, systemic change, and accountability from those who uphold systems that continue to disadvantage women. After all, it doesn’t seem too much to expect that all women:

- Live free from gender-based violence

- Are paid fairly for their work, with no gender pay gap

- Have equal opportunities for employment, without being held back simply because they are women

- Aren't penalised for taking on caring responsibilities

- Experience equal access to quality health care

Gender equality shouldn’t be a privilege that only a few experience. Sexism and misogyny shouldn’t be the standard. As Julia Gillard famously said in 2012:

“I will not be lectured about sexism and misogyny by this man. I will not… If he [Abbott] wants to know what misogyny looks like in modern Australia, he doesn’t need a motion in the House of Representatives, he needs a mirror.”

More than a decade later, Gillard’s words still ring true. Ultimately, the forces that drive gender inequality – sexism, misogyny, and systemic bias – haven’t disappeared. Gender inequality is something we’re still dismantling today. So now, over 10 years after our only female Prime Minister delivered these words, we need to take another hard look in the mirror and ask ourselves: what still needs to change to achieve true gender equality?