parties and election campaigns are funded – because those rules are

central to transparency, accountability, and integrity. In this PIMBY, we unpack recent steps toward reform, where the gaps still are, and why this is about more than just dollars – it’s about the health of our democracy.

Democracy under threat

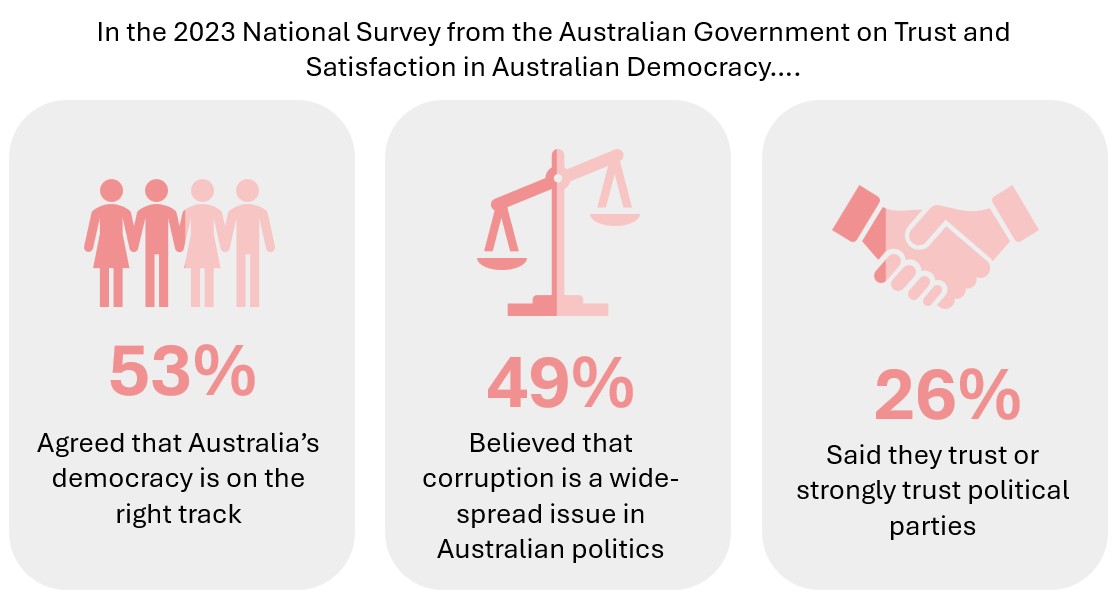

However, that doesn't mean everything is fine. A

recent national survey presented some concerning findings from respondents:

- Only 53% agreed that Australia's democracy is on the right track

- 49% believed the corruption is a widespread issue in Australian politics

- Only 26% said they trust or strongly trust political parties

According to the survey results, trust levels are even lower among women, people on low incomes, people who are unemployed, and those living in regional areas. So, there’s certainly work to do when it comes to improving transparency and accountability, reducing the influence of ‘big money’, and countering dis- and misinformation. And not just federally.

Democracy in Tasmania

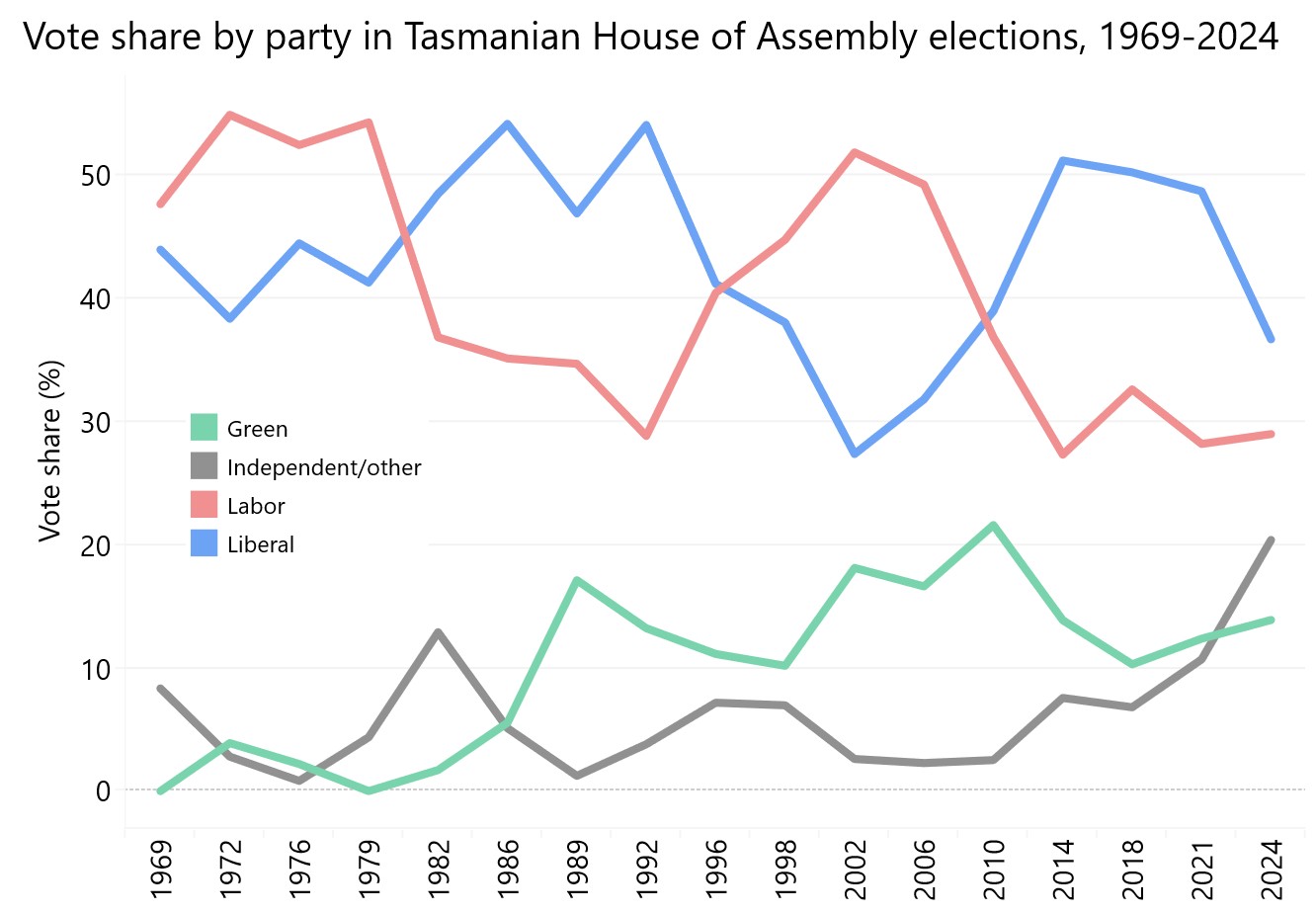

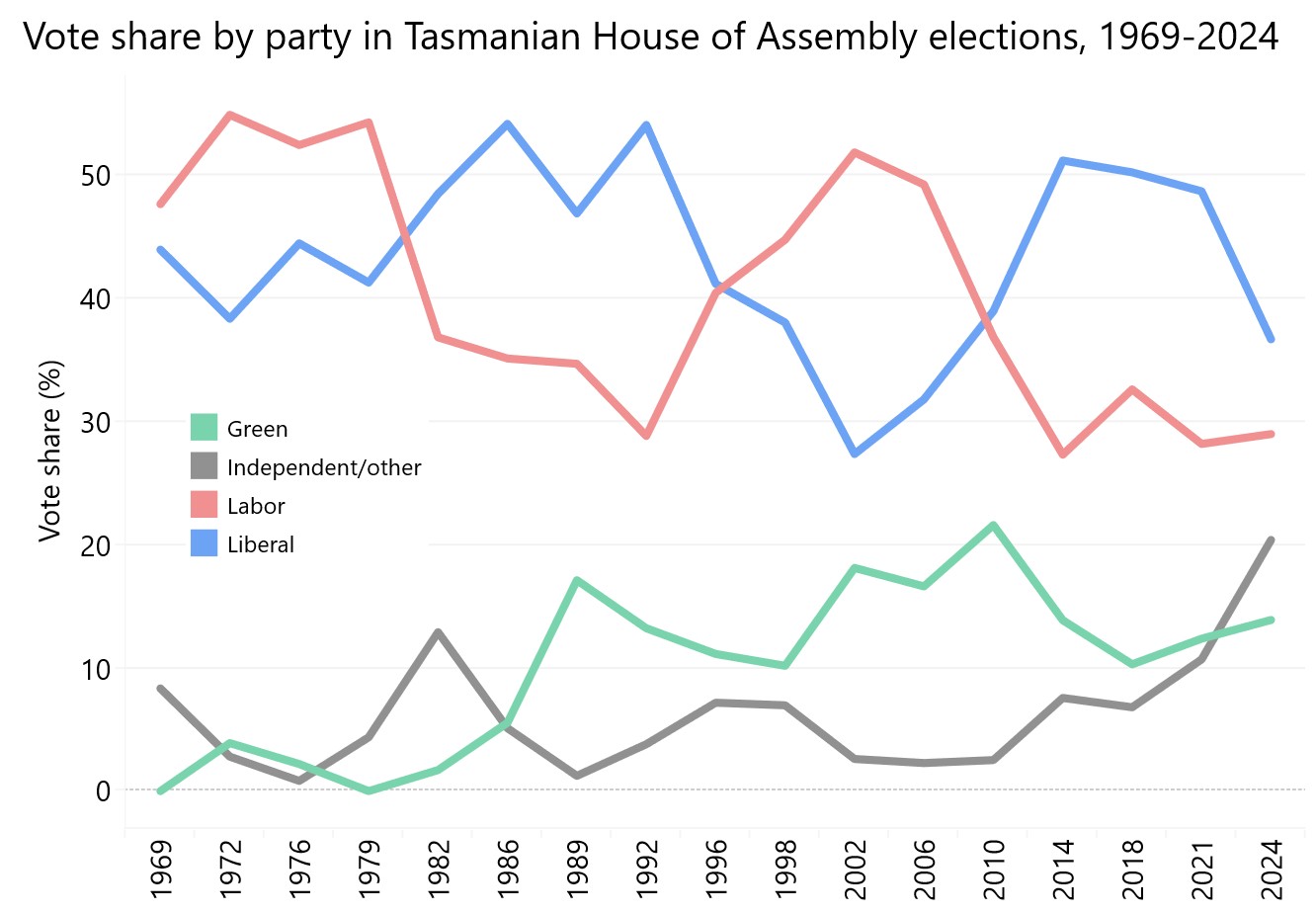

While there is no Tasmanian survey data on trust and satisfaction in democracy, there are other ways to understand how Tasmanians feel about our political system. For example, at the 2024 state election, Tasmanians voted in 11

non-major party MPs to the House of Assembly. That’s the largest number of independent and minor party members in the State’s history and a clear signal that voters are looking for change.

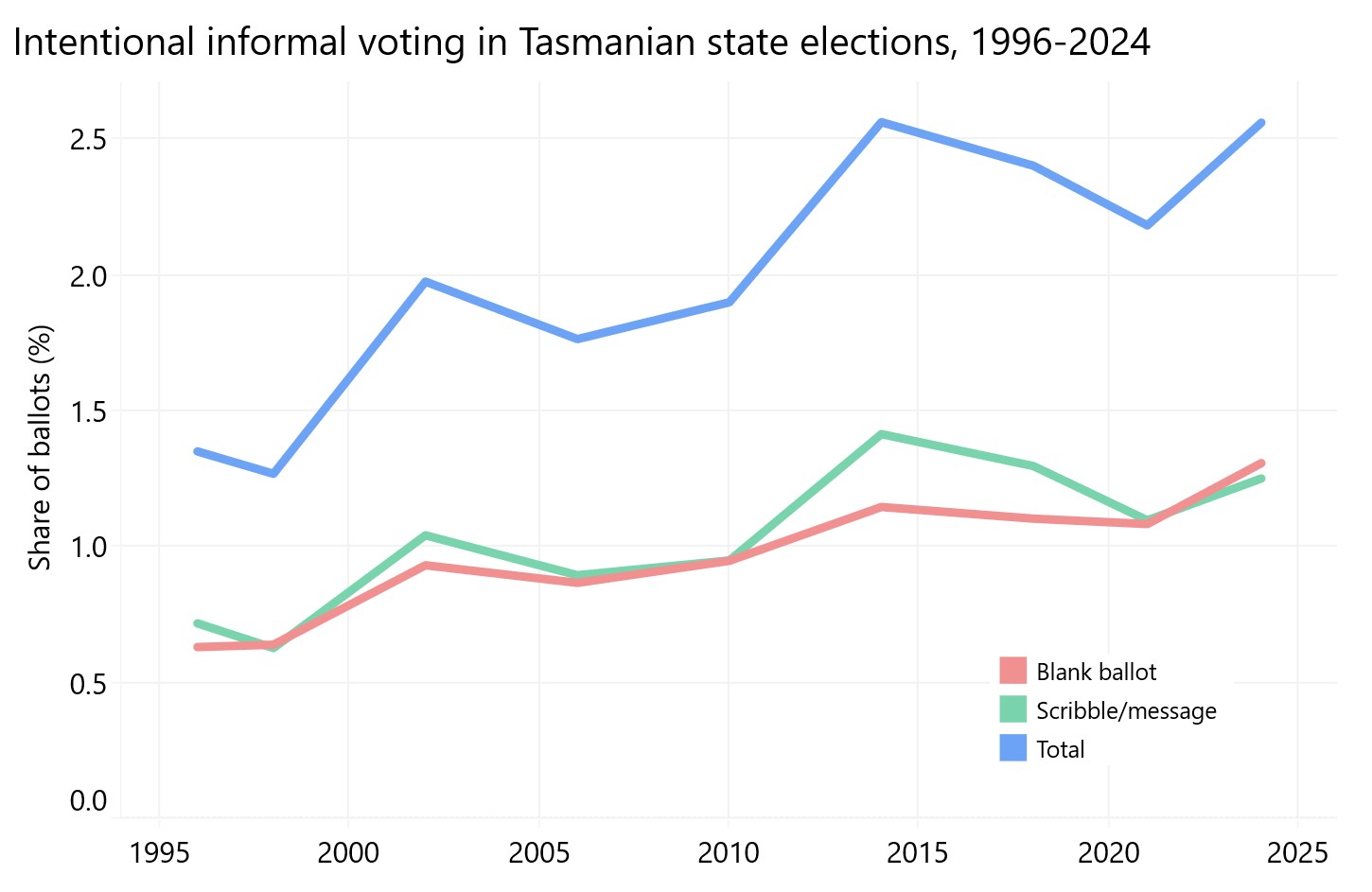

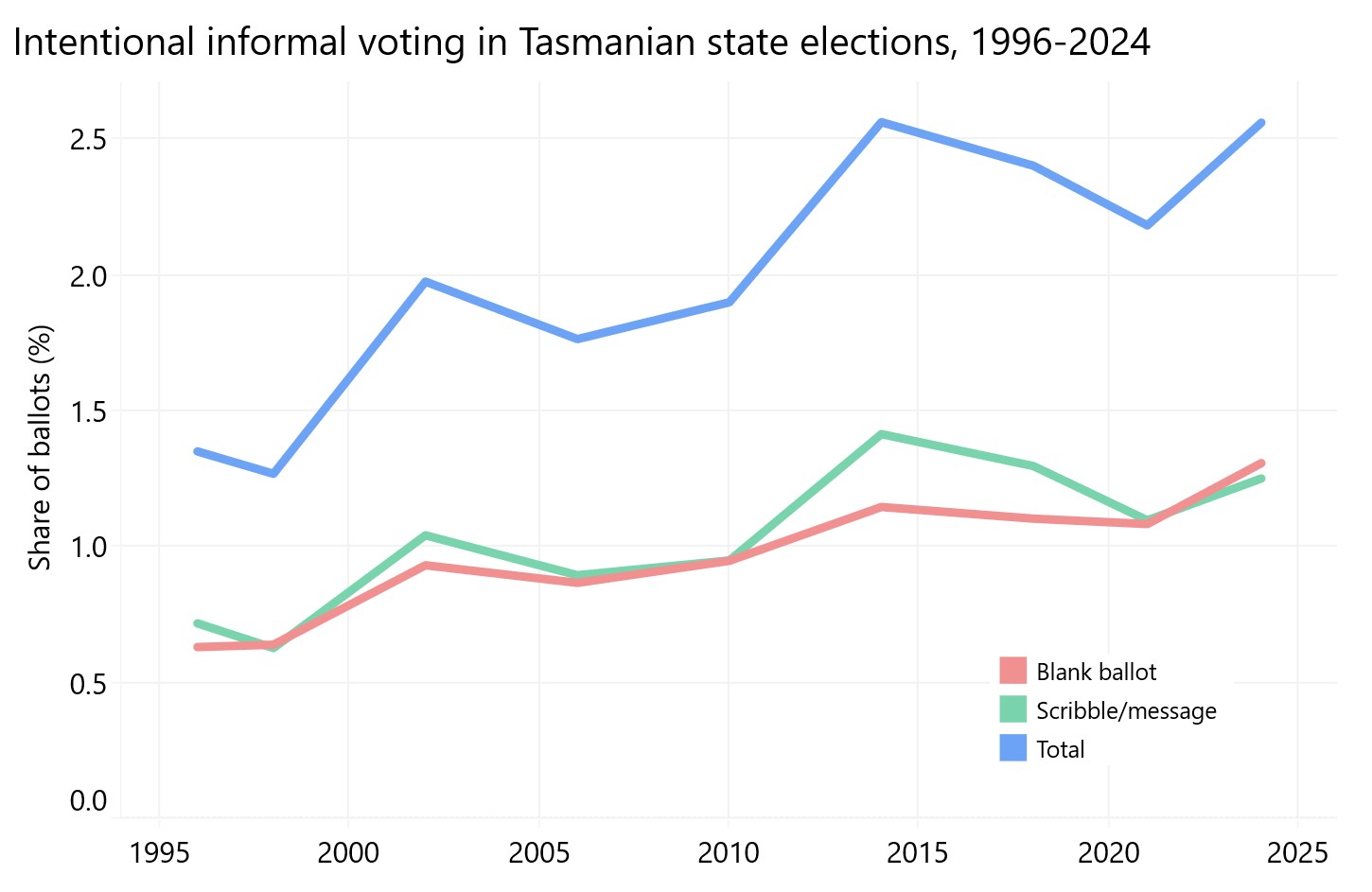

At the same time, we’re seeing a steady rise in “assumed intentional informal” voting. This is where people use their ballot paper to write or draw a picture instead of numbering the boxes, or leave their ballots blank.

Some researchers say this type of informal voting can indicate frustration or disillusionment with politics, although there are also

other explanations.

In Tassie, we’re seeing increases in assumed intentional informal voting. It might be time to consider that this isn’t a sign of a disengaged public, but rather a sign that people aren’t happy with how our political system works.

The most recently available data from the UTAS Institute for the Study of Social Change show that

only 31% of respondents felt like they had the opportunity to influence decisions about Tasmania’s future.

All of this points to a growing disconnect between voters and the political system – which means we need reform.

Why political finance matters

".... regulations related to the funding of political parties and election campaigns, commonly known as

political finance, are a critical way to promote integrity, transparency and accountability in any democracy"

-

International IDEA 2020Over the past decade, every mainland Australian state introduced major political finance reforms. And, until recently, Tasmania had mostly failed to do the same.

That changed in November 2023, when the Tasmanian Parliament passed the Electoral Disclosure and Funding Act. The main improvement was lowering the threshold for disclosing ‘political donations’ – defined as donations to a candidate, MP registered party, associated entity, or

third-party campaigner. Previously, donations only had to be declared if they exceeded the Commonwealth threshold of $16,500. The new Act required any donations over $5,000 to be publicly declared.

In 2024, the Greens proposed

an amendment to the Act, which put forward a range of changes. The only one to be successfully implemented so far has been lowering the donation disclosure threshold to $1,000. That’s an important step, but the other proposed reforms didn’t make the cut.

Below, we look at some of those proposed reforms: caps on campaign expenditure, rapid donation disclosure, and donations from corporations and other organisations. We’ll leave truth in political advertising for a future PIMBY – it’s a complex topic that needs the full treatment of a dedicated article!

Capping campaign spending

Currently, there are no limits on what candidates can spend campaigning for the Tasmanian House of Assembly. This is not the case for the Legislative Council, where campaign spending is capped (currently at $19,500). Putting a similar cap on lower house campaigns would go a long way toward making elections more

fair, competitive, and representative.

First, caps help reduce the time candidates and MPs spend chasing donations. That’s more time that could be better spent serving their communities.

In the United States, the pressure to raise money has become so extreme that members of Congress are reportedly expected to spend up to 30 hours per week just on fundraising – that’s more time than they spend debating legislation, developing policy, or engaging with their constituents. It’s hard to argue that’s in the public interest.

Second, caps make it easier for new and independent candidates to run. When the cost of campaigning is high, the field narrows, and incumbents are harder to unseat. When the cost of running a successful election campaign is too high, only people with access to considerable financial resources can get elected. Lowering campaign costs levels the playing field and introduces the possibility of a more diverse and representative mix of candidates.

Third, caps reduce the influence of powerful interests. In systems where fundraising is essential to winning,

candidates often become reliant on wealthy backers. The richer and more powerful the donor, the better. Unfortunately, not all donors are motivated by good intentions, and many want to see a return on their ‘investment’. Even if that influence isn’t explicitly transactional, it can still skew political priorities – especially when candidates know they can’t afford to campaign without support from powerful donors.

In addition,

evidence from

overseas has demonstrated that unchecked campaign expenditure reduces electoral competition, disproportionately benefits incumbents, and limits the field of candidates – all bad things in a democracy. None of this means campaign caps are simple to implement: controversy over

recent federal changes has reminded us that caps need to be carefully designed to make sure they don’t shut out new parties and candidates. But when done well, they make elections more transparent, more competitive, and ultimately fairer.

Real-time disclosures

Right now, there’s a delay in Tasmania between when a political donation is made and when voters find out about it. That matters, especially during election campaigns, because voters are trying to decide who to trust and should know who is backing whom. The 2024 amendment proposed that during an election campaign, all donations made in the seven days before polling day should be disclosed to the Tasmanian Electoral Commission (TEC) within 24 hours, and then published by the TEC within another 24 hours.

We think that this a good start, but the reforms could go further. In our view, the 24-hour disclosure and publication timeframes should apply from the start of an election campaign – not just the last seven days – until 48 hours before polling day. This is because many more people are now voting early, and they should be able to access the most

up-to-date information on whom candidates and parties have been receiving money from. To further strengthen transparency, we believe that donations shouldn’t be permitted in the 48 hours before election day. This prevents last-minute money from changing hands without public scrutiny. The bottom line is that voters ought to know how parties and candidates have been funded before they cast their ballots.

Outside of campaign periods, there is less need for rapid disclosure. Donations could be disclosed within seven days and published by the TEC. This would be similar to the system used successfully in

Queensland since 2016, where donations above a $1000 threshold are registered using a simple online database.

Together, these changes would make Tasmania a national leader in donation transparency. They reflect

Recommendation 2 from the federal Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters and align with international best practice, including

Transparency International’s call for real-time disclosure.

No anonymous donations from corporations and organisations

A more contentious proposal in the 2024 amendment was a ban on political donations from any entity that isn’t a person – which would prevent contributions from companies, trade unions, industry groups, and

non-government organisations. The theory is that this would

prevent powerful interests from exerting disproportionate influence on election outcomes, which is a legitimate concern.

However, there is a complication: corporations and other organisations can have legitimate political interests and should be free to exercise these by donating. Also, a full ban on all non-individual political donations would likely be

subject to a challenge in the High Court.

A better approach might be radical transparency. Instead of banning political donations made by a corporation or organisation, we suggest that they should be publicly disclosed, no matter how small. A disclosure threshold of $0 (meaning corporate donations cannot be anonymous) would ensure that

voters can see who’s giving money and to whom, without limiting legitimate political participation. and it is a cornerstone of Australian democracy. But when it comes to corporate and organisational interests and the role that organisations can play in public debate, we believe transparency should take precedence.

Call to action

In a time of global democratic decline and growing public disenchantment with democracy, Tasmania has an opportunity to lead the way on political finance reform. We’ve already taken small steps, but further changes could go a long way towards rebuilding public trust in our state’s political system.

We need our political leaders to step up and take bold action. This could look like capping campaign spending, rapid donation disclosures, and mandating transparency from powerful donors.

Tasmania has a chance to move forward and show that integrity, transparency, and public confidence in politics still matter. Let's not waste that opportunity.