You can see it playing out in our parliament as well. After another inconclusive election, the major parties publicly seem reluctant to negotiate on their core policy positions. Many of the crossbenchers were elected based on staunch opposition to these policies; if they back down, they will face the wrath of their constituents and lose their raison d'être. The result? A political stand-off that’s left some wondering whether Tassie is

ungovernable. One commentator has even suggested that we’re on our way to becoming a

failed state.

Clearly, something needs to change. And while there’s no silver bullet, there are good ideas out there. We touched on a few of these in

our last PIMBY – providing comprehensive training for new MPs, bringing parliament back into the budget process, and setting up agreements that make minority government work.

This time, we’re focusing on one idea in particular: deliberative democracy. Specifically, how it can be used

as a process for working through political disagreements. We explore what deliberative democracy is, how it works in practice, and what we can learn from places that have used it to break political deadlocks and rebuild public trust.

Defining deliberative democracy

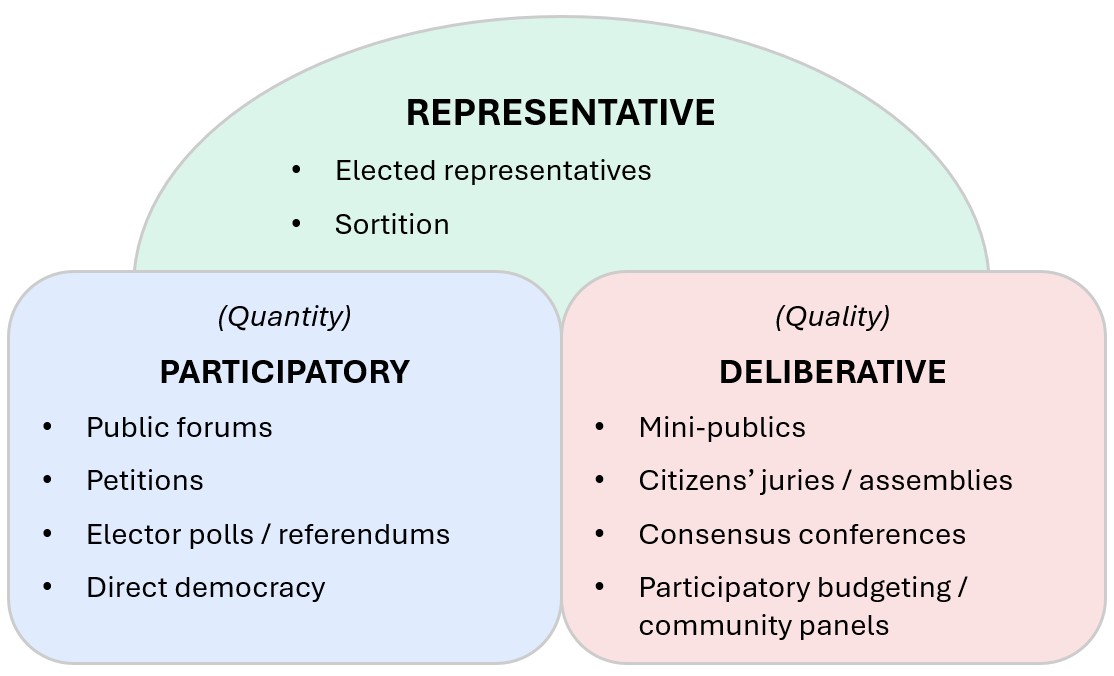

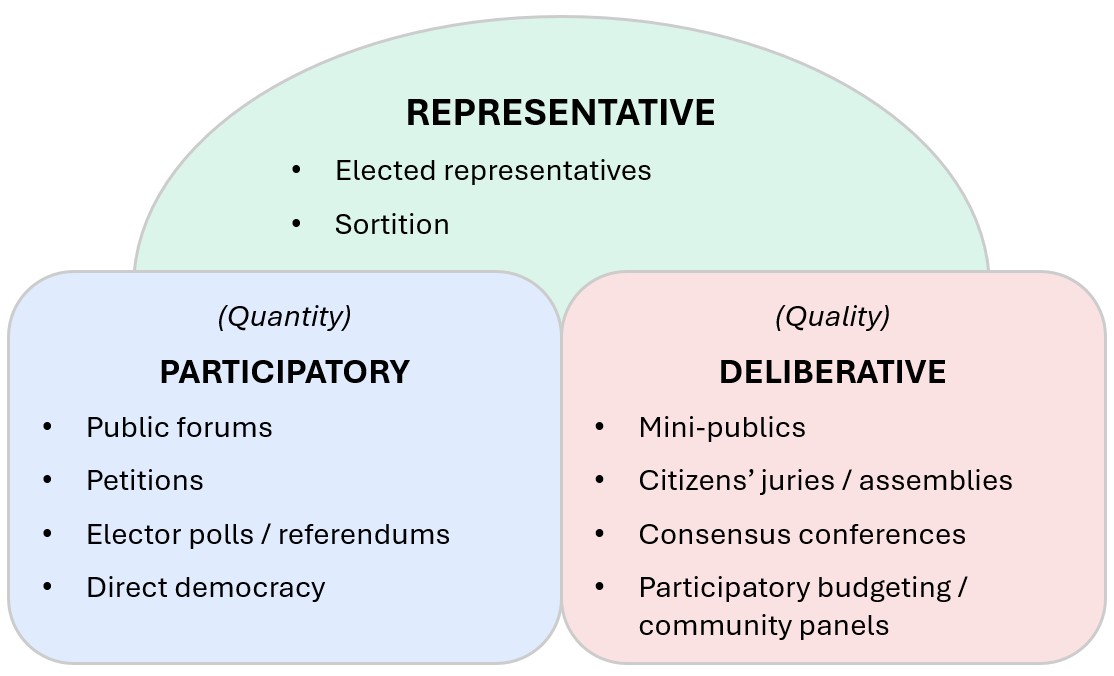

Before we dive into deliberative democracy, it helps to look at two other concepts: representative democracy and participatory democracy.

Our political system – and most modern democracies – operate primarily through

representative democracy. This means we elect people to make decisions and represent our interests in parliament.

This is the model we're most familiar with.

There's another form of representative democracy called sortition. This is where members of the public are randomly selected (like jury duty) to take part in decision-making. Sortition dates back to Ancient Athens, and although it’s not commonly used these days,

some argue that it could be used alongside elected representation to help bypass vested interests.

Participatory democracy, on the other hand, aims to involve as many people as possible in the decision-making process – usually through referenda, plebiscites or public votes. In Australia, national examples aren’t common but include the non-binding same-sex marriage plebiscite and the Indigenous Voice to Parliament referendum. In contrast, the Swiss model of

direct democracy means between 3 and 4 binding popular votes are held each year on specific issues. In Tassie, participatory initiatives are quite common at the local level – examples include elector polls on issues like the

Glenorchy Pool redevelopment, or the

relocation of the University of Tasmania's Sandy Bay campus.

Lastly,

deliberative democracy brings together a smaller, representative group of people (often selected by sortition) to explore a complex issue in depth. These groups receive information, hear from experts, and participate in discussions aimed at

finding common ground and producing recommendations. In this way, deliberative democracy initiatives aim to improve the

quality of decision-making processes. Examples of deliberative democracy in action at the local level in Tasmania include the

Hobart Climate Assembly,

Circular Head Youth Leaders, and the

Central Coast Access and Inclusion Working Group.

Importantly, these three models aren’t mutually exclusive. They're often used in combination. Citizens’ assemblies (deliberative) often select participants through sortition (representative), and may make recommendations that are later put to a public vote (participatory). Australia’s Federal Parliament is chosen through elections (representative), but for big issues that require changes to the Australian Constitution, we hold referenda (participatory).

Case studies from around the world

To get a better idea of how deliberative democracy operates in the real world, we’ve looked at three case studies. We’re not saying these are perfect – but they offer valuable lessons about what works and what to watch out for.

1. IrelandIreland’s citizens’ assemblies are widely seen as an effective model – though it hasn’t all been smooth sailing. There have been six so far, with the first in 2013 and the most recent in 2023.

A good example was the 2016

Citizens’ Assembly, which was established to deliberate on five challenging and potentially divisive topics, including abortion, fixed-term parliaments, and climate change. A long list of participants was randomly selected through a national lottery, then narrowed down to a group of 100 using a set of criteria designed to ensure representativeness. The group met across 12 weekends in 19 months, with travel expenses reimbursed to enable participation. The Assembly was chaired by a former Chief Justice and supported by an expert advisory panel. At each session, participants listened to a range of speakers and had discussions in small groups run by trained facilitators.

The most

high-profile outcome was the Assembly’s recommendation to repeal Ireland’s near-total ban on abortion. This eventually led to a national referendum and a major shift in public policy – a significant outcome for an issue that had been

hugely divisive.

Ireland has since used citizens’ assemblies for other issues, including biodiversity loss and gender equality. The recent Biodiversity Assembly made 159 recommendations –

over 90% of which are now in progress or implemented.

Still, there have been challenges. A 2021 attempt to update the Constitution on gender equality failed at

referendum – raising concerns about low public buy-in, the influence of lobby groups, the representativeness of participants, the quality of evidence and debate, and how outputs are

translated into real-world decisions.

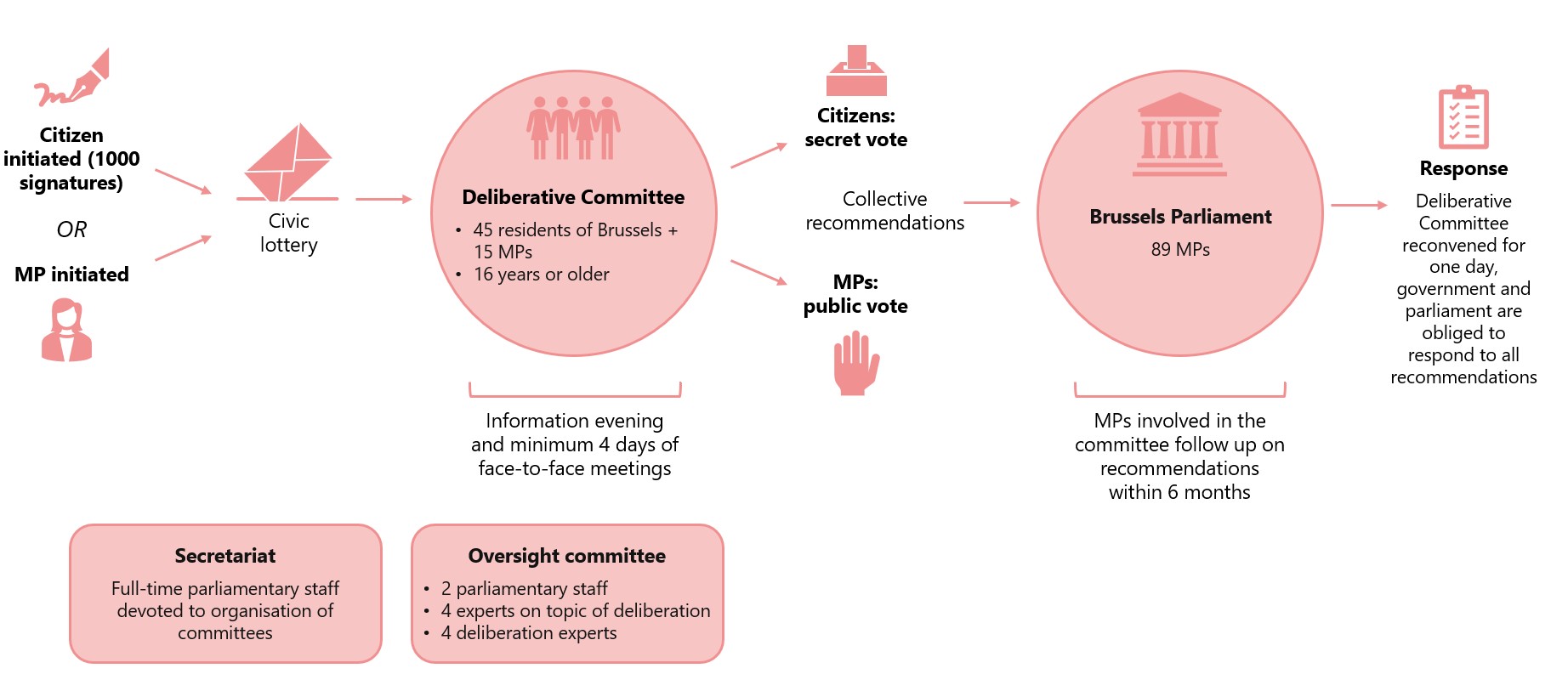

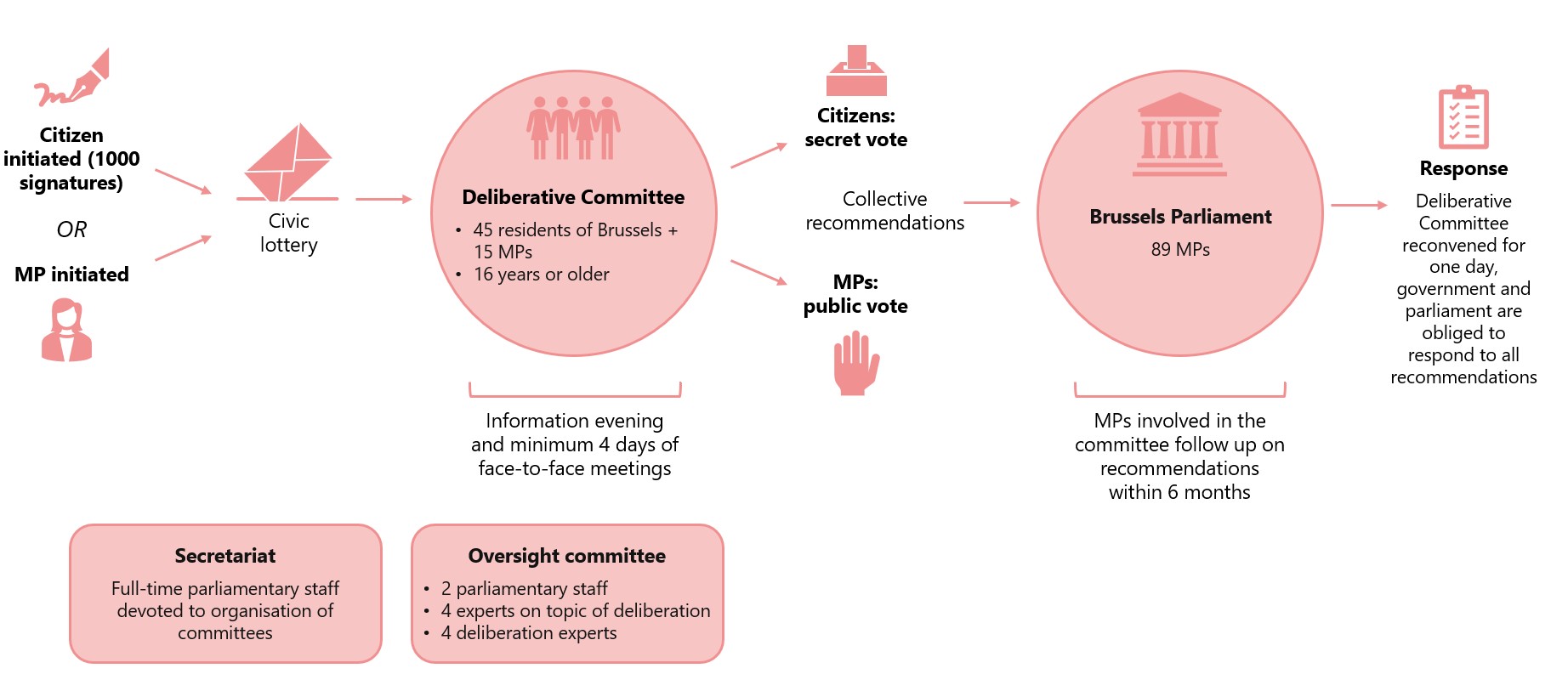

2. BelgiumIn Brussels, deliberative democracy has been embedded more formally into the parliamentary process through Deliberative Committees. These committees bring together citizens and elected MPs to develop recommendations on specific topics – such as rolling out a 5G network, homelessness, and crisis response. The process for instituting a Deliberative Committee is set out below:

Some other important

design features include:

- Topics must fall within parliament’s jurisdiction and can’t be reduced to simple yes/no answers

- Participants receive a stipend and are offered accessibility supports such as child-minding services

- Citizens and MPs receive training on critical thinking and unconscious bias

- Elected representatives must respond to recommendations within six months

- An evaluation process may recommend changes to the model after each committee finishes

This process has been credited with helping to build trust, improve collaboration across party lines, and tackle complex problems.

However,

there are still challenges. Some committees have been dominated by MPs, and others faced legitimacy problems when elected representatives changed recommendations without consulting the citizens who were involved. A lack of public awareness about the committees could be limiting their impact on public debate. But the inbuilt evaluation process is being used to address these challenges, highlighting the

importance of improving the model over time.

Deliberative democracy is also well-established in other parts of Belgium. For example, in the community of Ostebelgien, a ‘

Permanent Citizens’ Dialogue’ has been in place since 2019. And it looks like momentum is building, with other regions

currently looking at introducing Deliberative Committees.

3. BrazilFrom 1989 to 2017, the Brazilian city of Porto Alegre used participatory budgeting – giving citizens real power to shape how public funds were spent. At its peak in 2004, this pioneering model engaged over

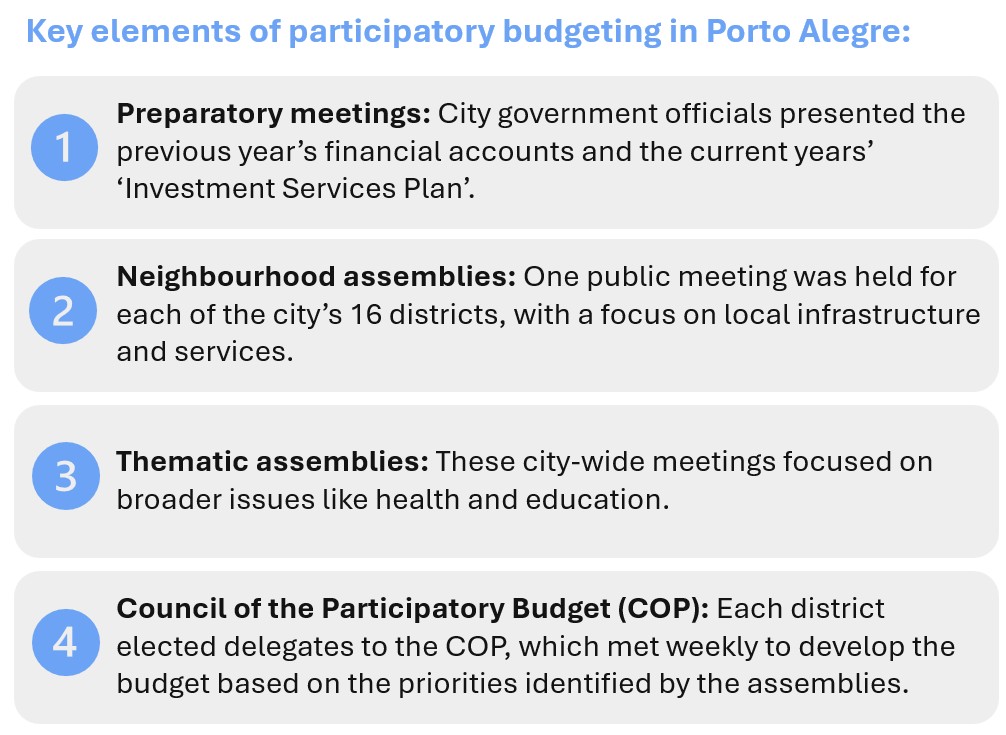

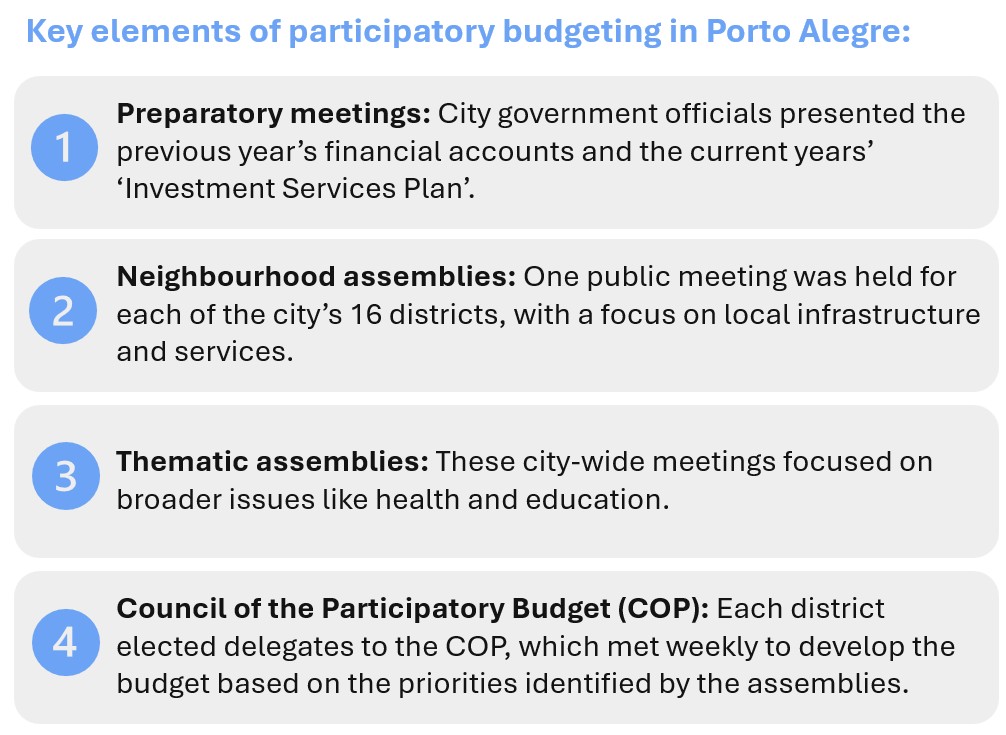

50,000 citizens and allocated around $160 million in public funds. The process changed over time, but typically featured a few key elements:

This model was designed to combat corruption and situations of competing interests.

It was praised for redistributing resources more fairly and better supporting underserved areas.

However, critiques emerged over time. While the model was highly effective for smaller community-level projects, it struggled to handle long-term planning and city-wide infrastructure decisions. When political support faded following a change in government, participatory budgeting was sidelined and eventually suspended in 2017 – a reminder that even well-designed deliberative processes can

fall apart if they’re not supported and institutionalised.

Doing deliberative democracy right

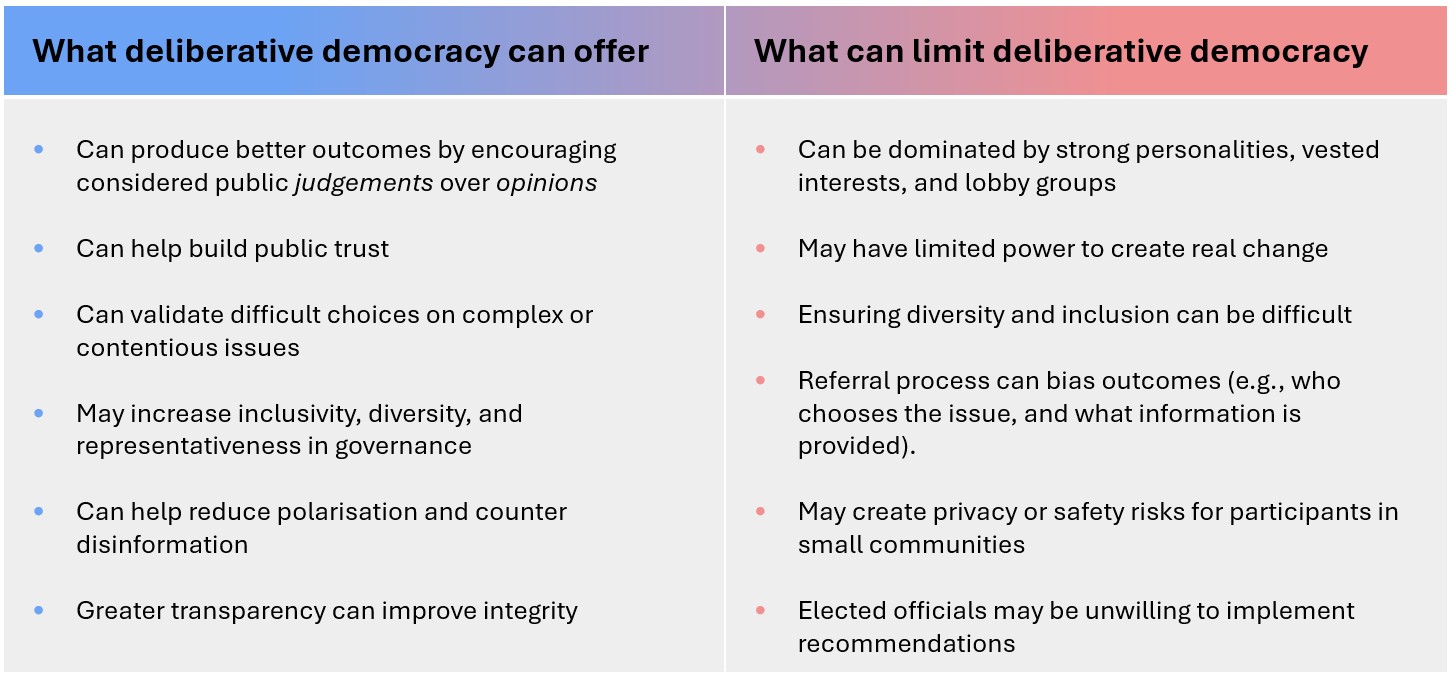

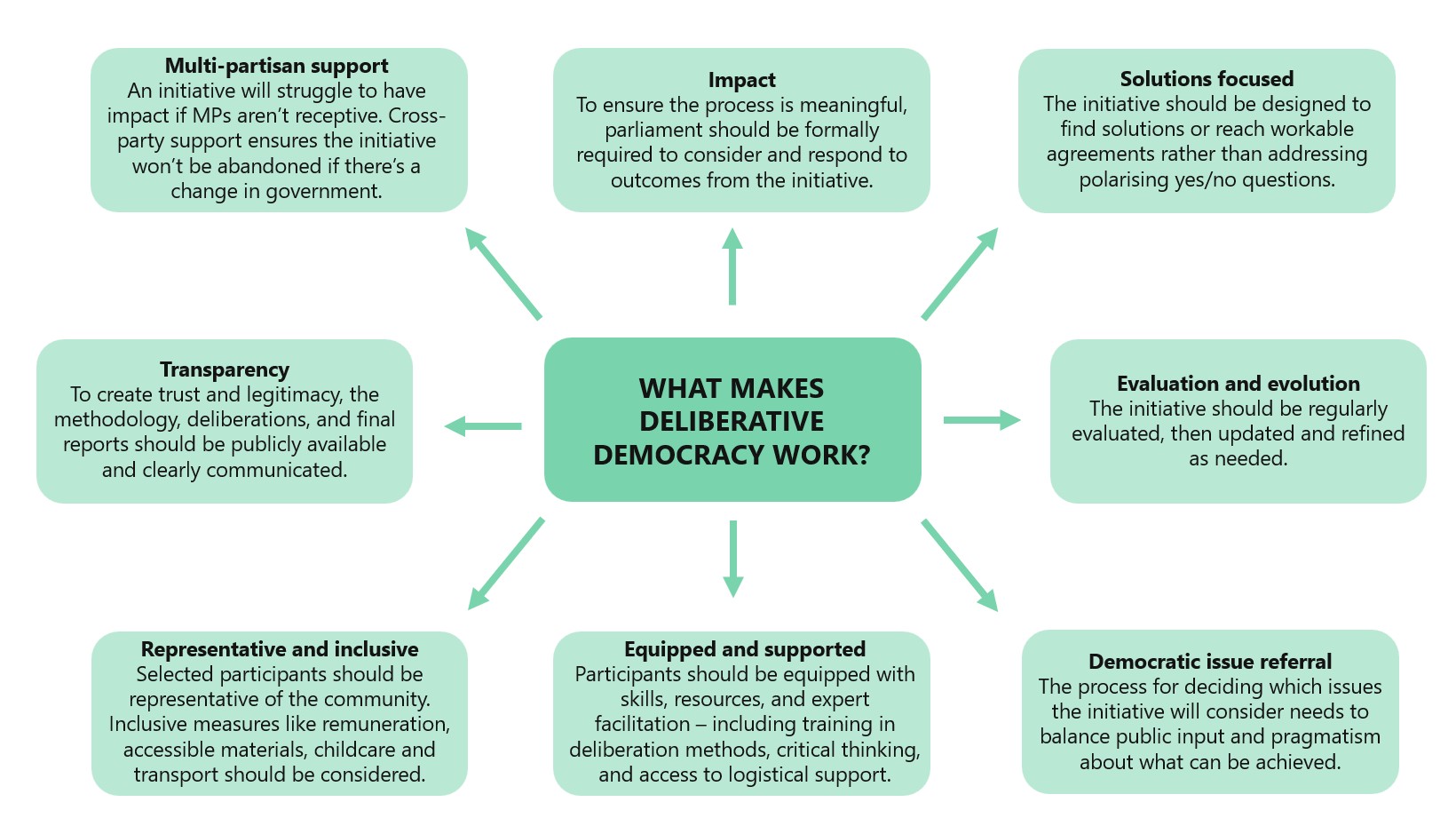

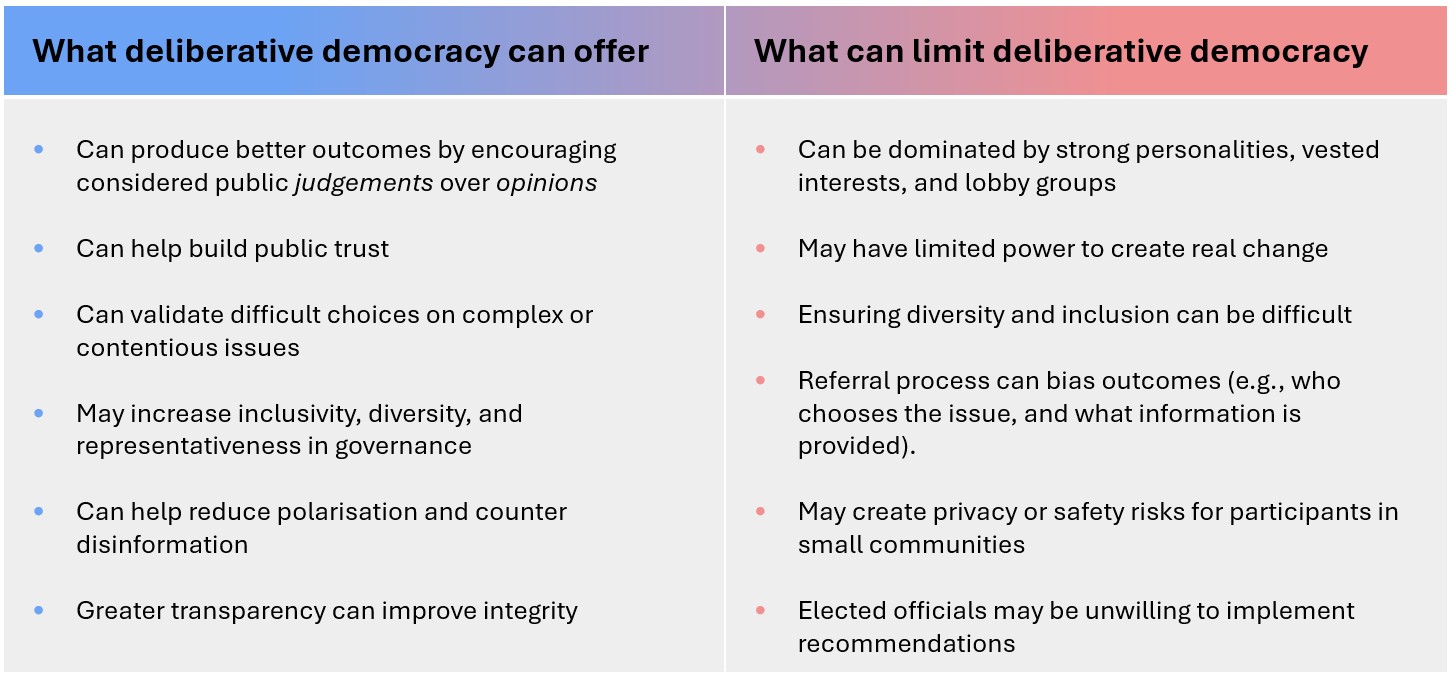

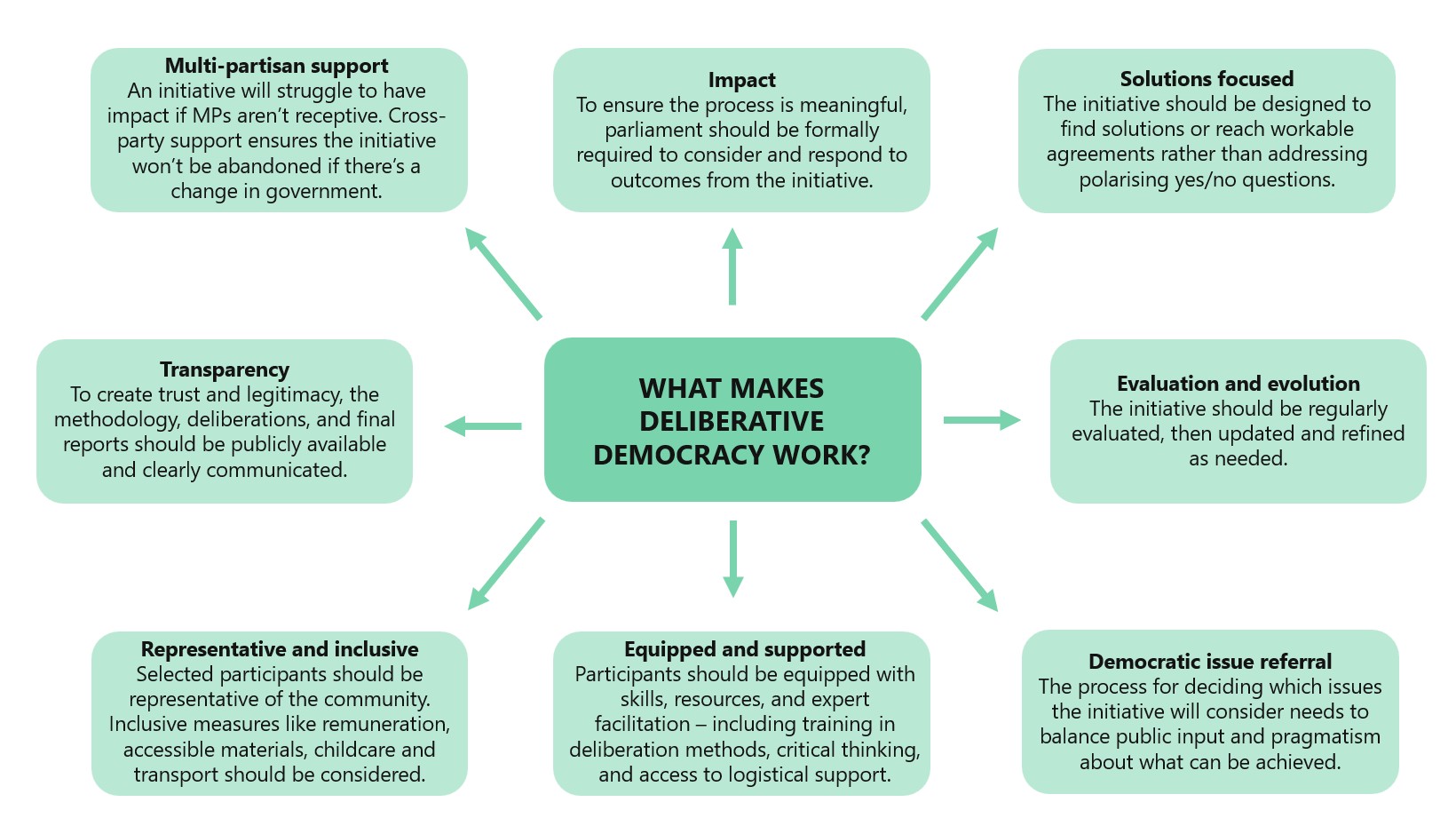

The three case studies show that deliberative democracy can help tackle complex, contested issues – but success depends on the process being well-designed, properly resourced, and taken seriously by decision-makers. To summarise:

These challenges aren’t deal-breakers. Most of them can be addressed through awareness, thoughtful design, and strong institutional support.

The point being, deliberative democracy is no longer a radical idea. There are many

examples from around the world of initiatives becoming invaluable parts of the political system.

The big question for us is what could deliberative democracy look like at a state-wide scale in Tasmania?

As we’ve seen, there are many models out there and there’s no one-size-fits-all approach. To come up with a Tassie version that reflects our unique context will need a public conversation about what we want to achieve. But as this PIMBY shows, there are a few things that it’s really important to get right:

Deliberative democracy won’t solve all of Tasmania’s problems – but it could help us find common ground on the issues that divide us. It’s not about politicians dodging political responsibility when a hard decision needs to be made. Deliberative democracy is about generating fresh ideas, getting people more interested and involved in democratic processes, and finding a path forward on some of the issues that have divided Tasmanian society for years.