Tasmania's history of minority government

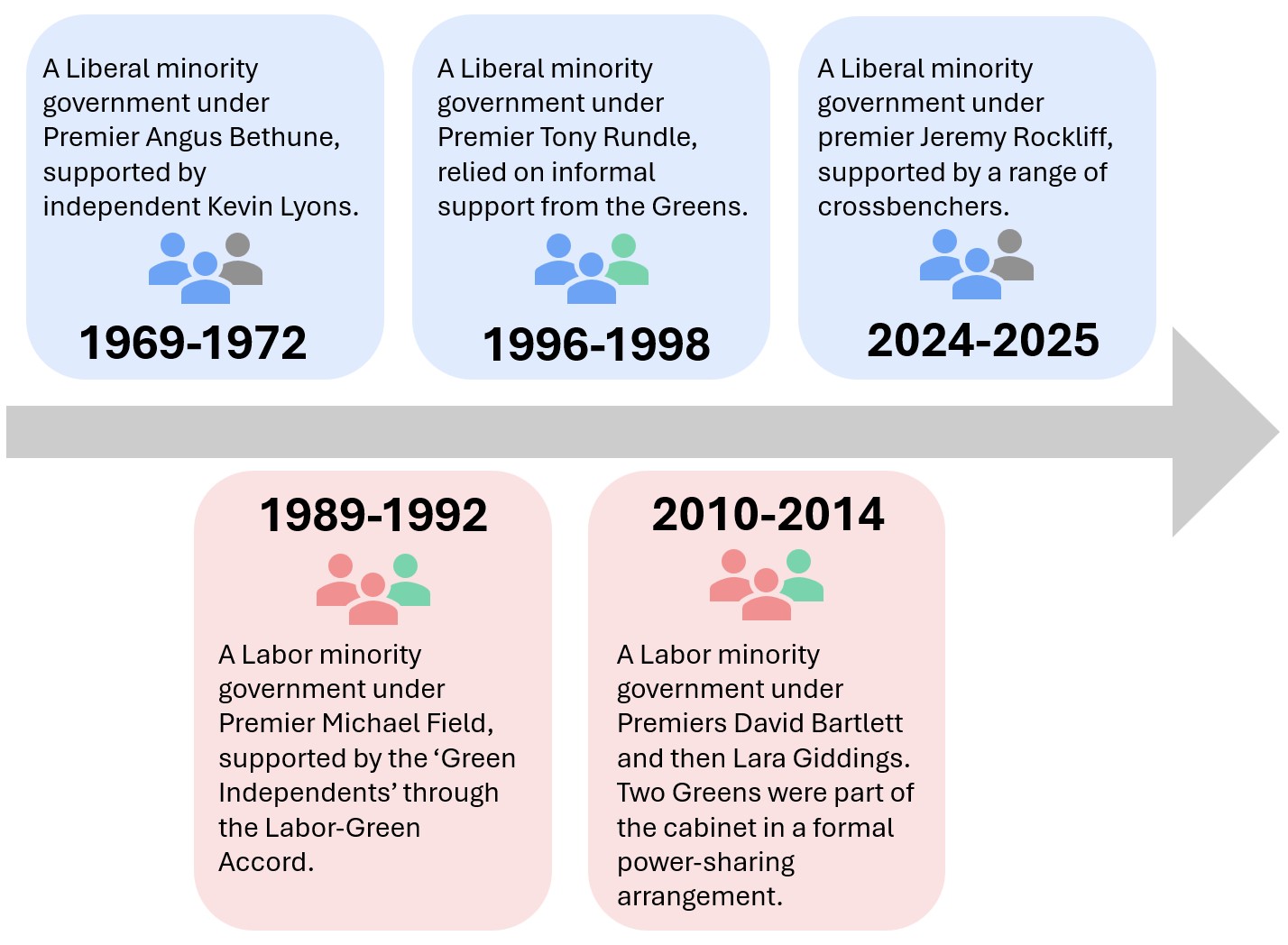

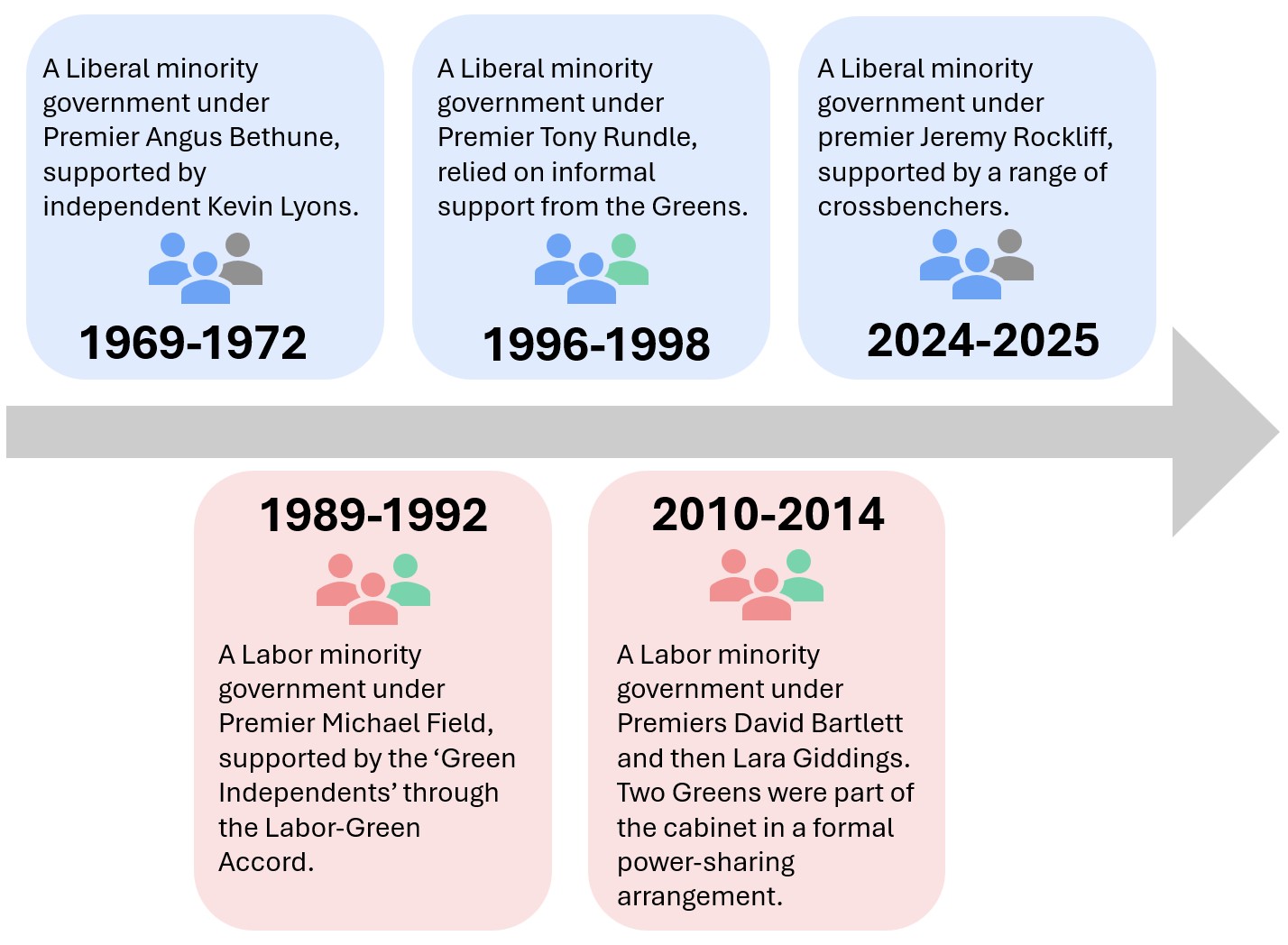

For all the talk of minority government being the ‘new normal’ in Tasmania, it has happened throughout our history. Since 1950, there have been five:

For a deep dive on how some of these governments operated, check out

Dr Mike Lester’s PhD thesis. There’s also been plenty of recent debate about the legacies of these past minority governments in Tasmania (see

here and

here).

On balance, we don’t believe the level of bad press that minority government receives in Tasmania is justified. These governments achieved some

important policy reforms, and often had to contend with

challenging economic circumstances beyond their own control.

Whatever your take on the matter, one thing is clear: minority government is a

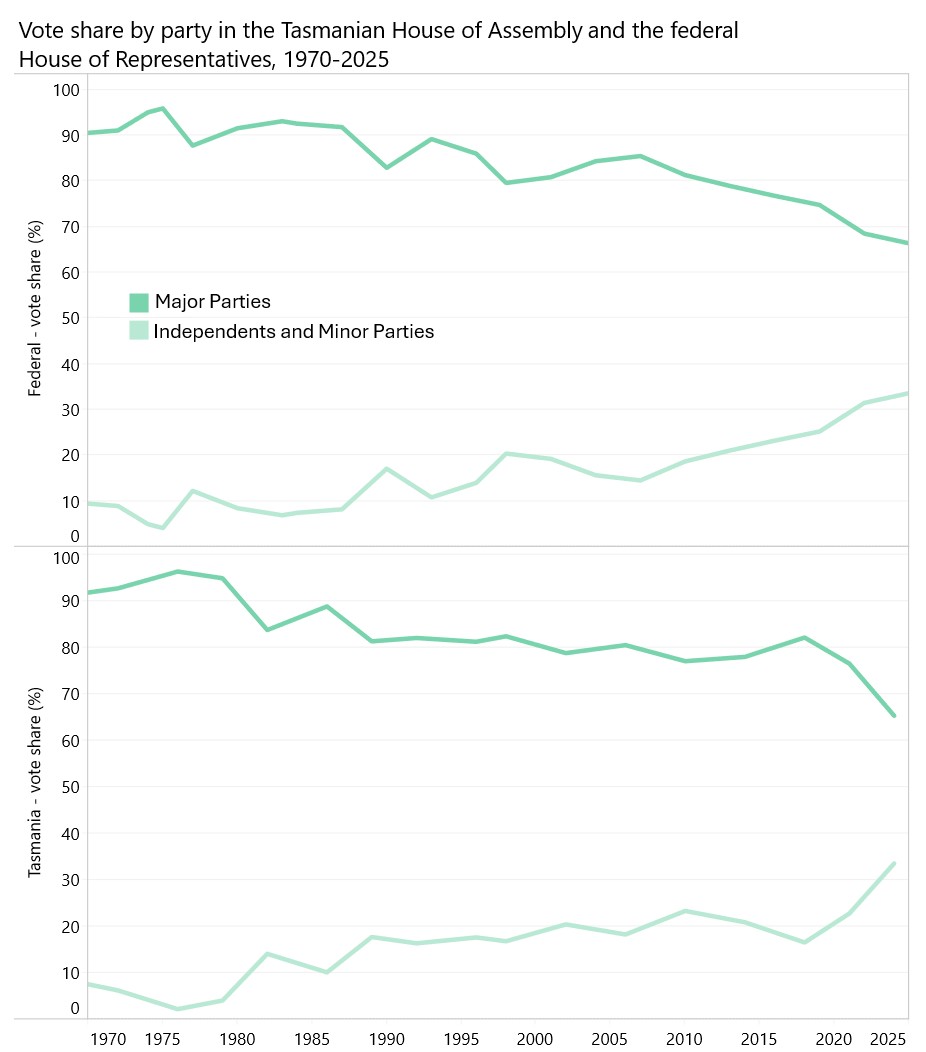

recurring feature of Tasmanian politics. In fact, if you look at voting trends overtime, it’s

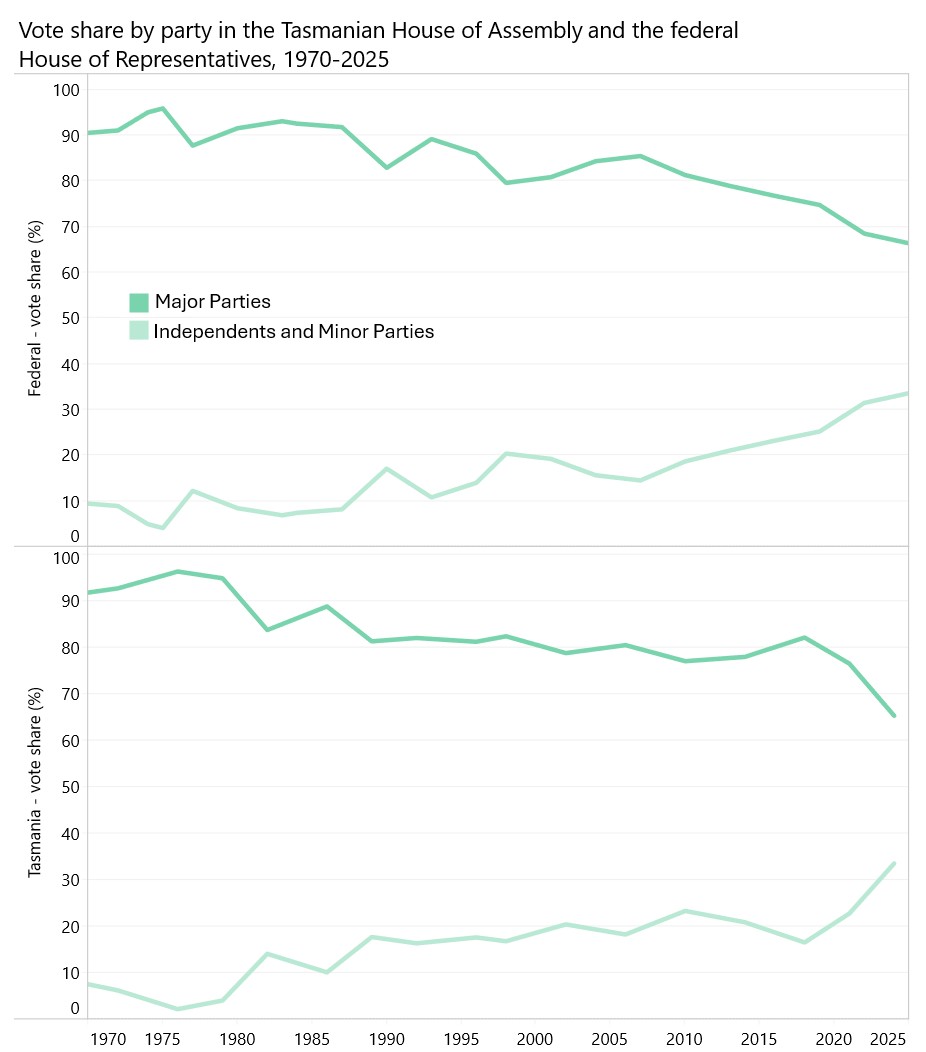

getting harder for either major party to win outright:

If this pattern holds, minority government is likely to become even more common. Which means the real task at hand is figuring out how to make minority government work well, for the good of the state.

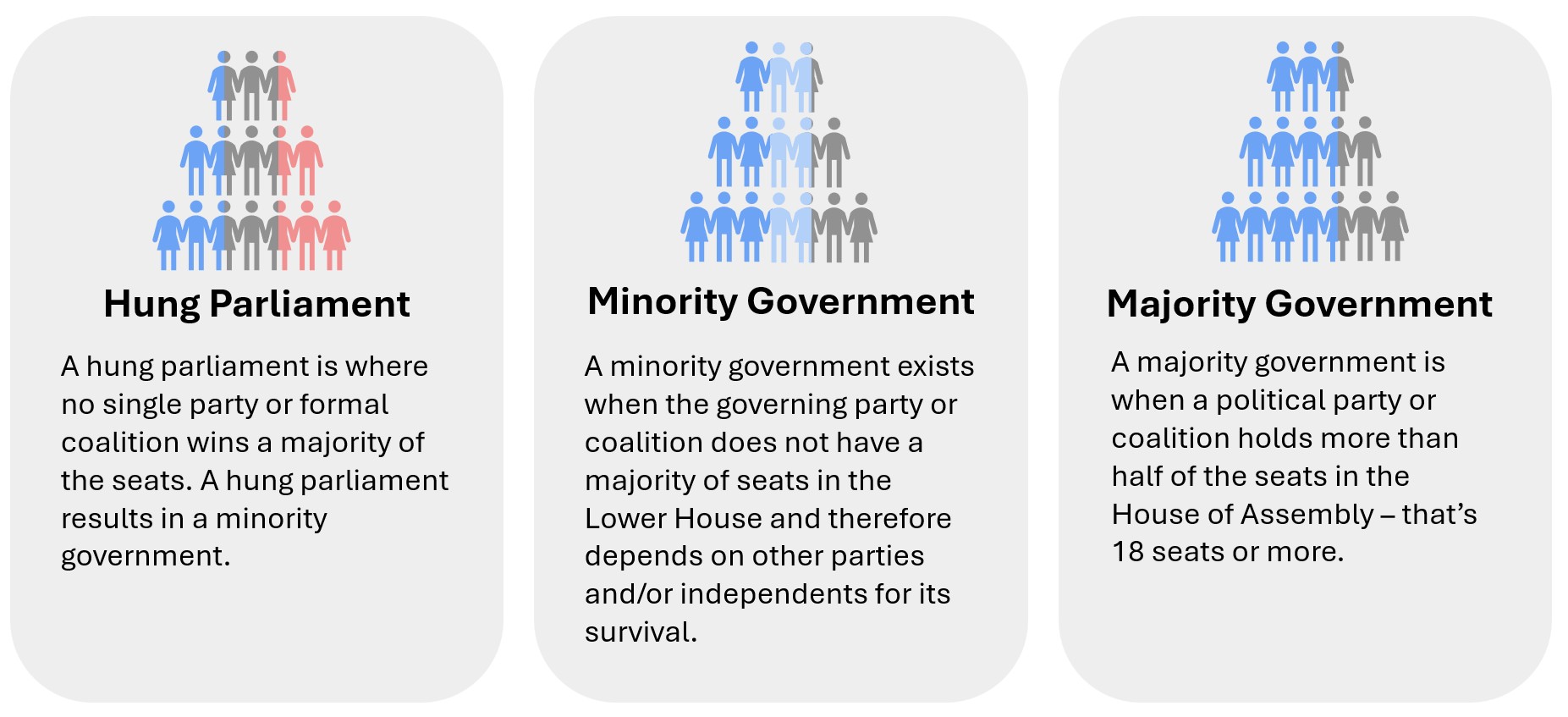

The current post-election situation

Before we look at what’s happening now, a quick reminder: in our Westminster system, voters don’t directly choose the government. We elect members of parliament, and those members determine who forms government. The government is accountable to the people, but

through the mechanism of parliament.

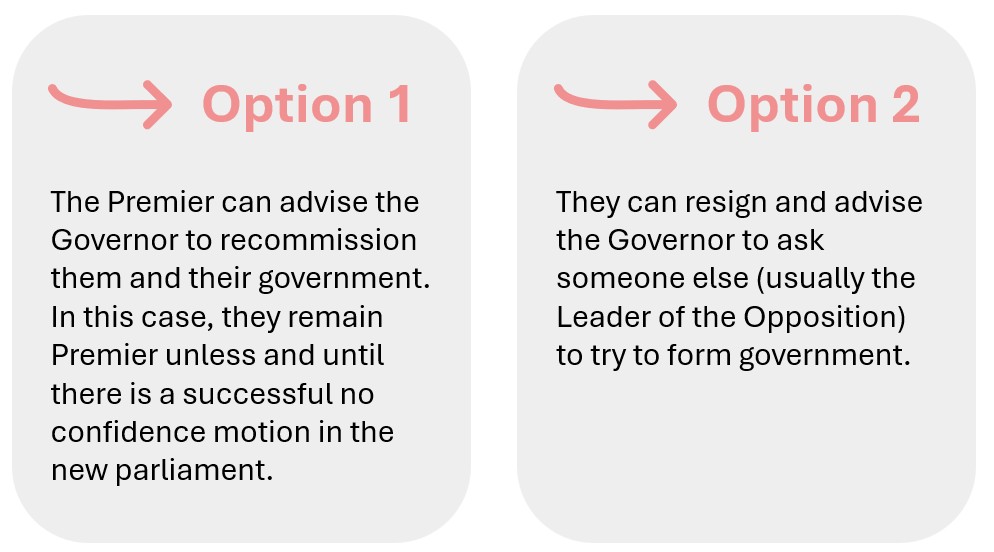

A parliament with no clear majority doesn’t mean the state is leaderless or in crisis – it just means the usual post-election process is more complex. By convention, the

incumbent Premier initially retains power. Assuming they don’t take

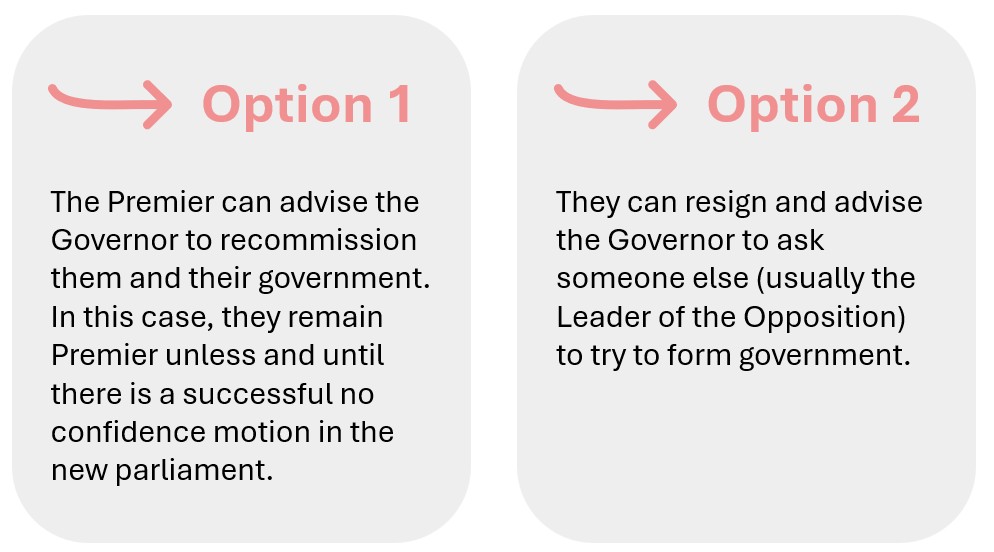

David Bartlett’s 2010 approach, the premier has two main options:

Premier Jeremy Rockliff announced on election night that once results are final, he will advise the Governor to recommission his government. Between now and the return of parliament, he’ll be working to lock in enough support from the crossbench – ideally through formal confidence and supply agreements – to avoid losing an immediate no-confidence motion. If it becomes clear that he can’t secure enough support, Rockliff might still resign. But based on past form, this is unlikely.

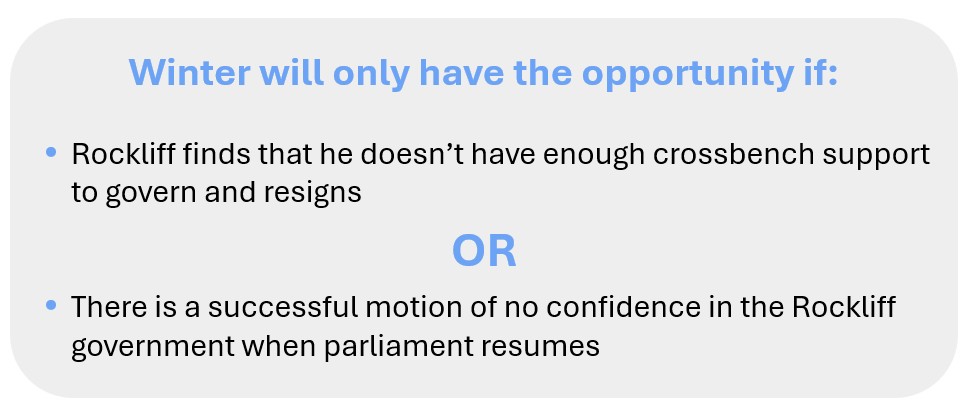

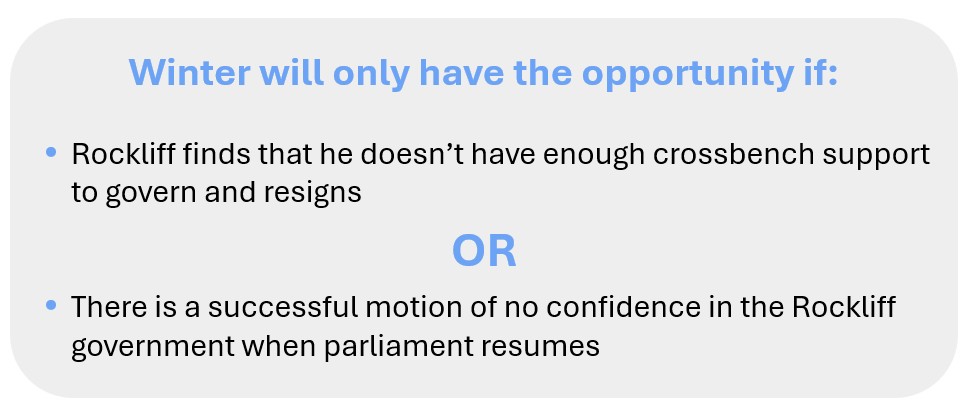

Labor leader Dean Winter hasn’t ruled out forming a minority government himself, but his options are more limited than Rockliff’s.

That’s why Winter is also

currently meeting with crossbenchers. So, while Rockliff has the advantage, both leaders are working behind the scenes to build crossbench support. In the end, that’s what government is all about: who can command the

confidence of the parliament.

Making minority government work

Whether we end up with a Liberal- or Labor-led minority government, the kind of agreement reached with the crossbench will matter. There are many options, ranging from bare-bones confidence and supply agreements to more formal arrangements where MPs from independent or minor parties join cabinet – or something in between. But no matter what the agreement looks like, or how detailed it is, it won’t be enough on its own.

To really work, minority government needs a fundamental shift in our parliamentary culture. The Westminster system is inherently adversarial – just look at the way the chamber is set up, with two sides facing off like opposing armies. But that doesn’t mean we can’t change things. Systems built on convention, like ours, can evolve for the better. We need principles and processes that support more collaboration, informed debate, transparency, and accountability – not just winner-takes-all-politics.

Fortunately, we don’t have to start from scratch.

Roughly one-third of Australian state and territory governments since World War II have relied on crossbench support, and other countries have been making minority government work for years. From South Australia to Canberra and New Zealand to

Denmark, there are proven ideas from which we can draw inspiration.

Let’s look at a few of them.

Process over policyThere’s currently a lot of debate about what policy demands the crossbench might make in return for their support. But it’s not enough to just focus on policy – process matters too. Former Premier David Bartlett, who negotiated the 2010 Labor-Greens power sharing arrangement, argues that success comes down to

trust and having clear processes for managing disagreement. In Germany, coalition agreements include a ‘

Koalitionsausschuss’(coalition committee) that leads

coordination and dispute resolution.

Building on this,

Professor David Adams recently suggested that any minority government agreement in Tassie should do three things:

Together, these measures could form a foundation for a more collaborative, transparent approach to governing.

It’s encouraging that the Liberal Party’s recently released ‘

Foundations of Stability framework’ includes some of these elements. And as Professor Adams has argued, the language we use matters too. Talking about “power sharing” or “collaborative government” might help to move away from the negativity associated with the term ‘minority’.

Learning the parliamentary ropesYou might be surprised to learn how little formal training Tasmanian MPs receive, despite the importance of their job. New members are given a brief induction that includes an overview of parliamentary procedure, but that’s about it. Compare this to

New Zealand, where new MPs receive a comprehensive 3-week induction.

The goal shouldn’t be just to teach rules – it should be to prepare MPs to work effectively and ethically in a complex system with other parties, experts, and the public. MPs from established parties often pick up some of this through their internal party networks, but for others any such training is ad hoc. That’s a missed opportunity.

A more comprehensive training program could cover essential topics and, just as importantly, create the opportunity for MPs to build relationships and trust across partisan lines – something that’s crucial for a collaborative parliament. There are several existing training programs that Tasmania could use as a model, including the

CPA Parliamentary Academy,

Next25, and the

McKinnon Institute.

Bringing parliament back into policy

One of the hallmarks of successful multi-party systems is that parliament plays a more active role in developing policy. While the government should always be responsible for making final decisions and implementing programs, political standoffs are less likely if parliament is more involved in policy development.

Let’s take budget repair as an example.

One option is to establish a multi-partisan budget review process at the start of the new parliamentary term. This would bring together all MPs – including those from the Legislative Council – to discuss submissions from Treasury,

independent experts, and the public. The goal would be to establish broad budget priorities and parameters, rather than setting the annual budget – which should always be the role of the government. The Liberal Party’s proposed ‘

Multi-Partisan Budget Matters Panel’ seems to be a step in this direction, although it’s not yet clear how the panel would operate.

Additionally, an independent

Parliamentary Budget Office could provide advice and track progress throughout the term.

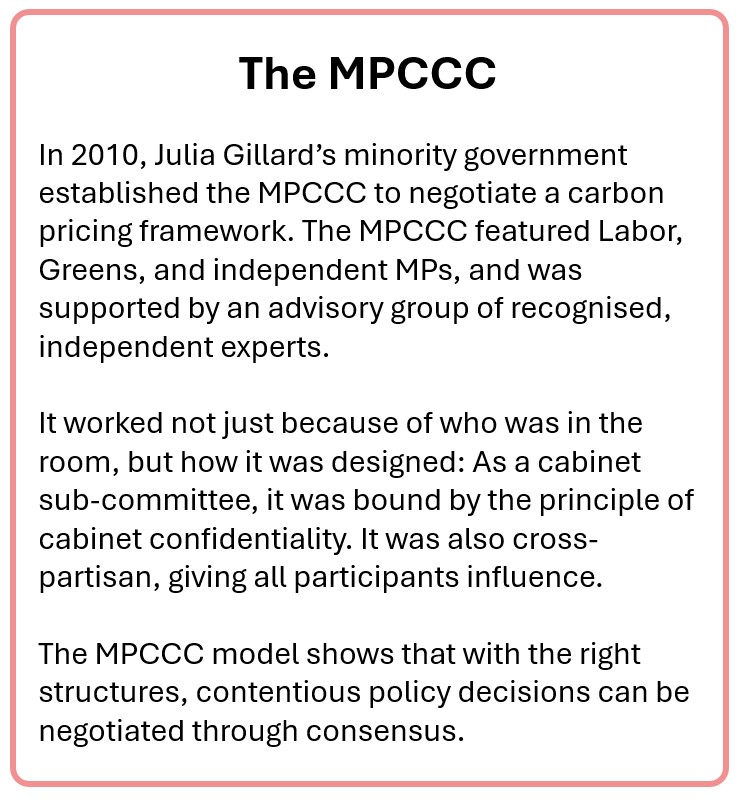

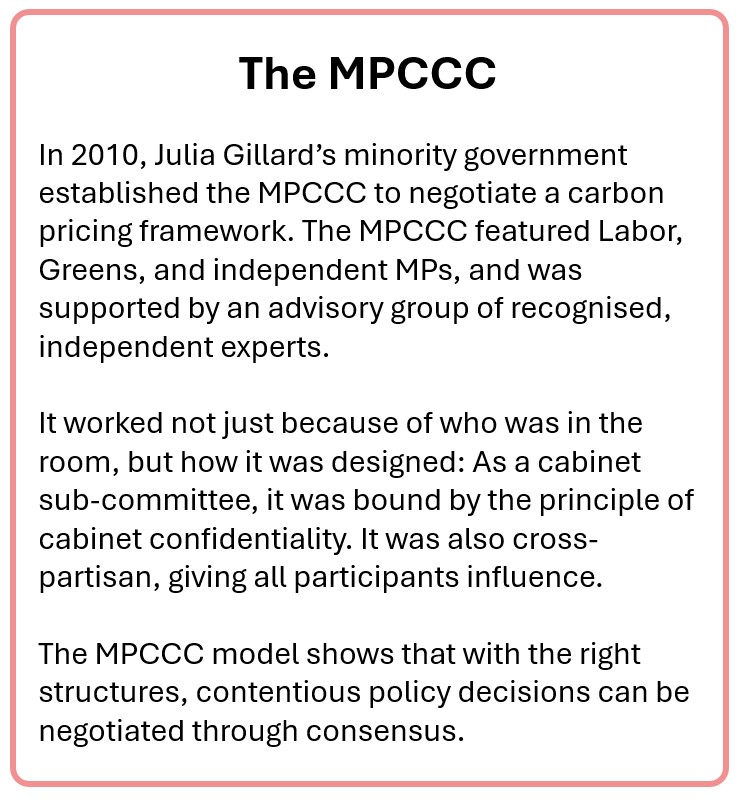

Another option would be to create a cabinet sub-committee like the Gillard Government’s ‘Multi-Party Climate Change Committee’ (MPCCC). A budget repair cabinet sub-committee could include nominated lower and upper house MPs of all political stripes. To join the committee, MPs would need to agree to a set of principles, such as acknowledging the need for action and respecting the confidentiality of proceedings. The committee could be supported by a group of respected independent experts.

This model isn’t as transparent as a public budget review process, but sometimes a degree of confidentiality is required to negotiate tough political compromises.

Refresh, revive, thrive

There’s no shortage of ideas for refreshing how Tasmanian politics works. Independent MLC Meg Webb is arguing for

fixed four-year parliamentary terms. Former Greens leader Christine Milne has been

posting about a ‘Government of state unity’. Independent MLC Ruth Forrest has been giving her thoughts on addressing the state’s big challenges. Other mechanisms such as

citizens' assemblies and

conscience votes could help ensure legislation is assessed on its merit rather than through a party-political lens.

We’ll talk more about some of these ideas in future PIMBYs but for now, what matters most is recognising that cultural change in our parliament will take time. New Zealand is a case in point. When it

shifted from ‘first past the post’ to ‘mixed member proportional representation’ in 1996, the early years were rocky. The new coalition government struggled to find its footing and there was scepticism about whether the new system would work. But overtime, the political culture slowly changed. It is often still adversarial, but according to former Deputy Prime Minister

Jim Anderton:

The new politics is about having to work with other ideas. … Decisions that would have been made on the floor of the caucus of one party are now made around the Cabinet table, with other parties present, and other ideas present, and are made in consultation with other parties that are not even in Cabinet.

The ideas we’ve discussed in this PIMBY would need to be debated, refined, and adapted to Tasmania’s unique context. But if minority government really is going to be more common, then we need to change our approach. For the good of our state, let’s hope that Tasmania can learn from places that have found ways to make collaborative government work.