This edition of PIMBY outlines Tasmania’s growing health challenges,

examines how election promises like Medicare reforms and Urgent Care Clinics stack up, and asks what’s still missing from the bigger primary healthcare picture.

A state in poor health

During the election campaign, both major parties have promised to boost Medicare rebates with the aim of improving access to GPs. But as this PIMBY argues, we also need to focus on supply. Access is about affordability – can you afford to see a doctor? Supply is about availability – can you find a doctor to see? Addressing one without the other risks leaving major gaps in the healthcare system, particularly in Tasmania.

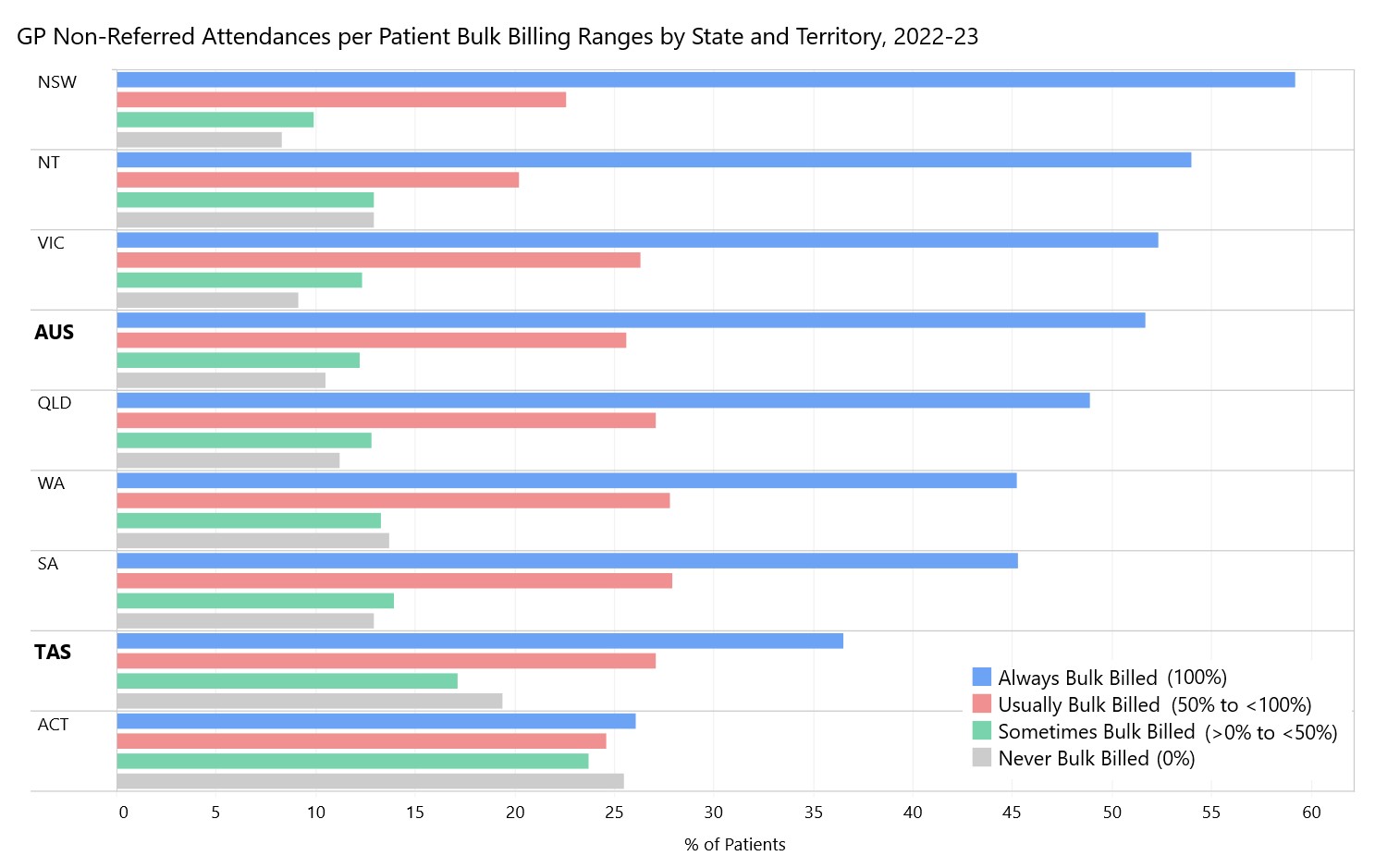

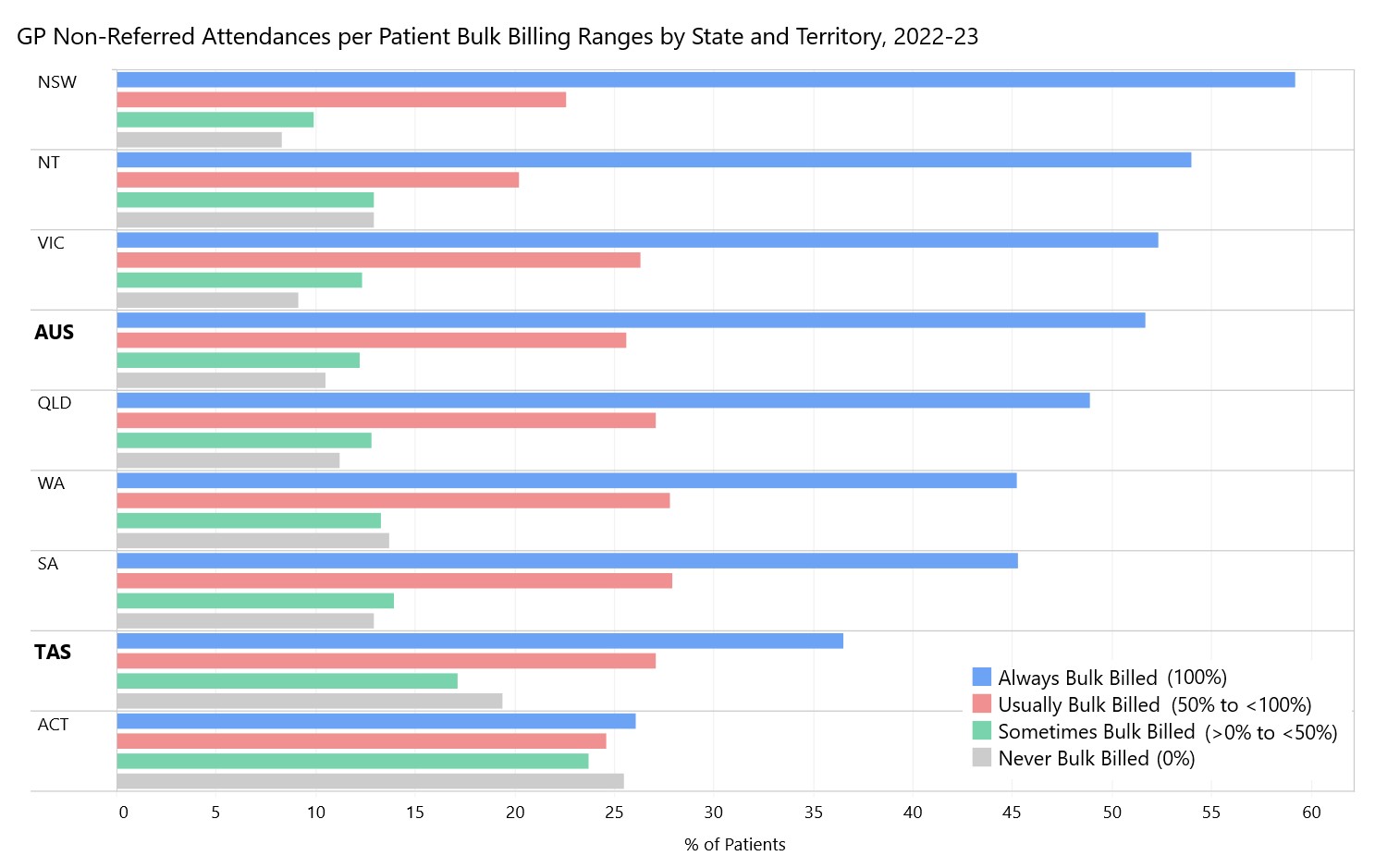

The challenge is that Tasmania has a serious problem when it comes to accessing affordable healthcare. The

Cleanbill GP Directory reports that no GP clinic in Tasmania currently bulk-bills new adult non-concession patients. We are a long way from

the promise of universal access to healthcare when Medicare was first unveiled. The chart below shows how striking Tasmania’s situation is compared to the rest of the country. Tasmanians are much less likely to be “always” bulk-billed and more likely to face out-of-pocket costs when seeing a GP.

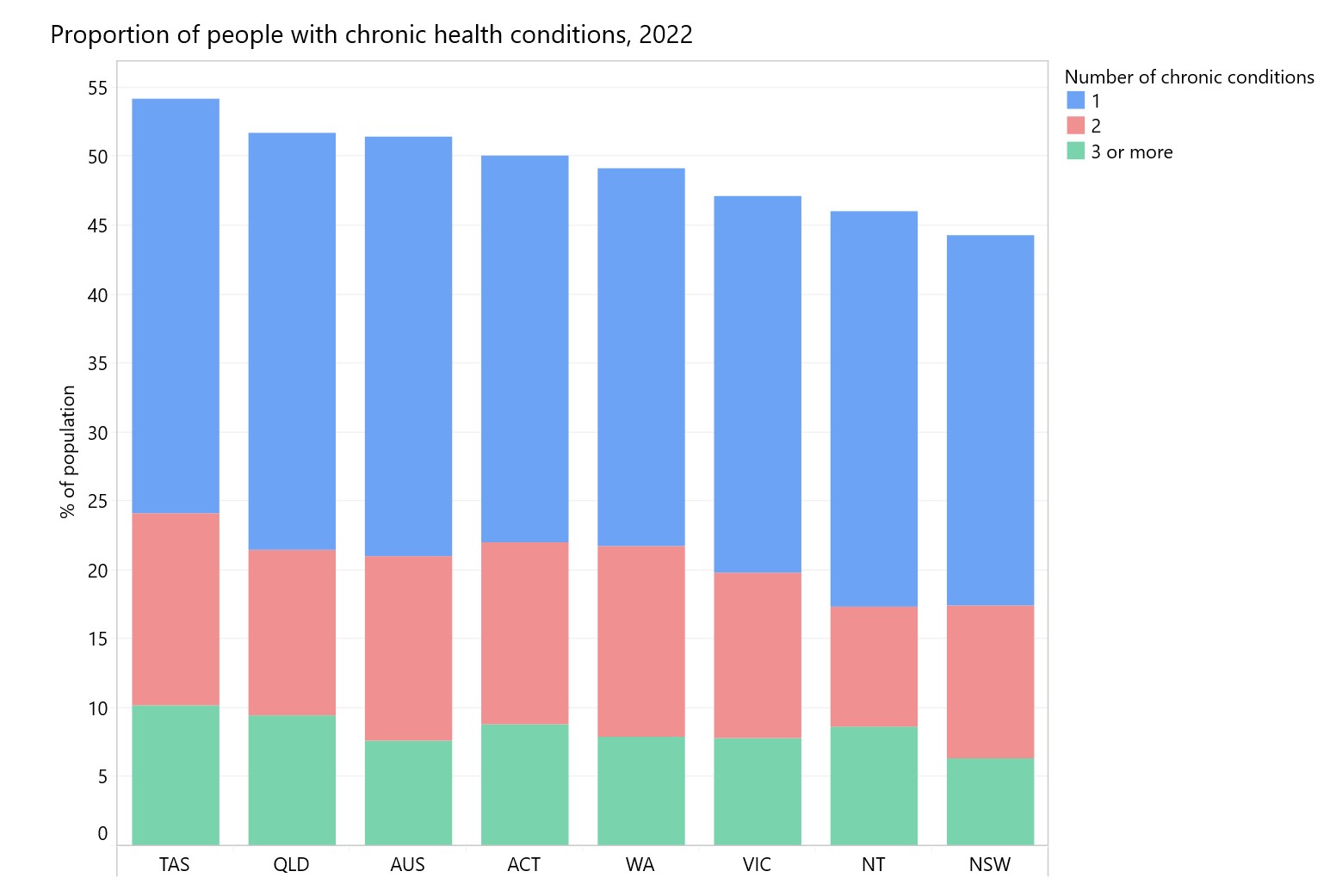

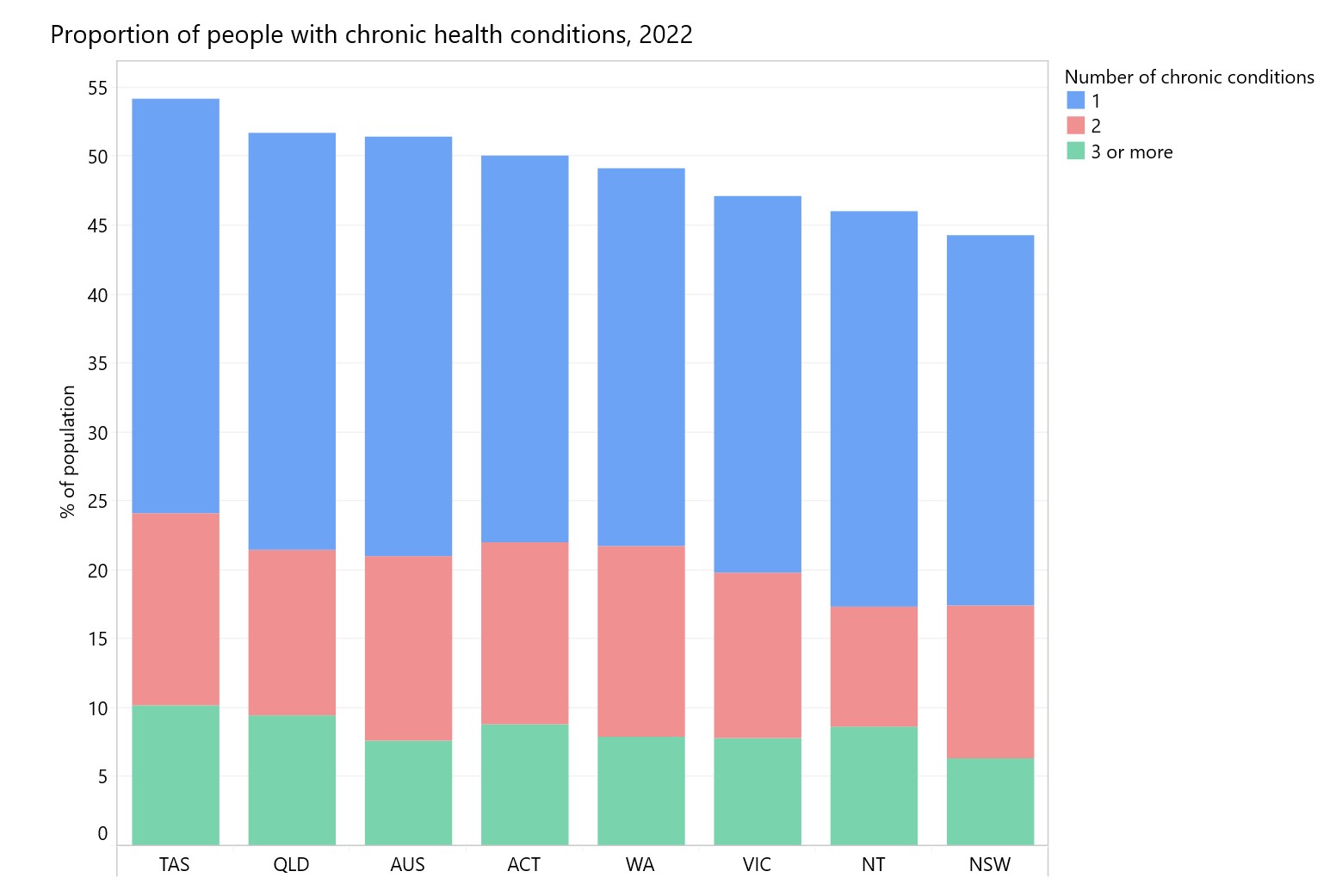

Lack of access to affordable healthcare in Tasmania is a major concern given our poor health outcomes. As of 2022, more than half of Tasmanians (54%) were living with at least one chronic health condition – the highest of any state or territory. And for many, it’s more than just one issue– around 10% of Tasmanians are managing three or more chronic conditions. That’s well above the national average of 7% and noticeably higher than the 6.3% reported in NSW, for comparison. On top of this, Tasmania has an

ageing population and

fewer resources to pay for delivering care.

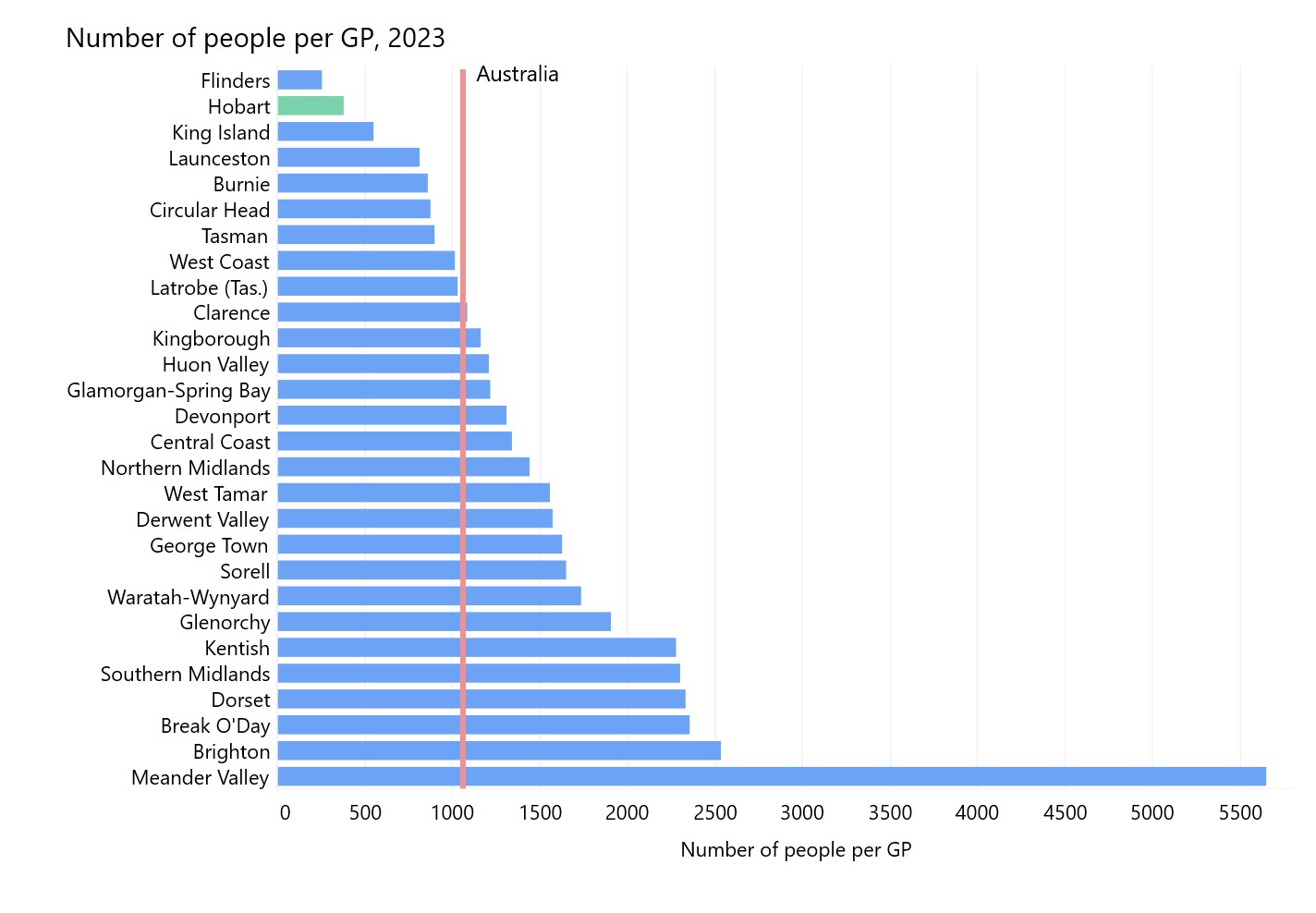

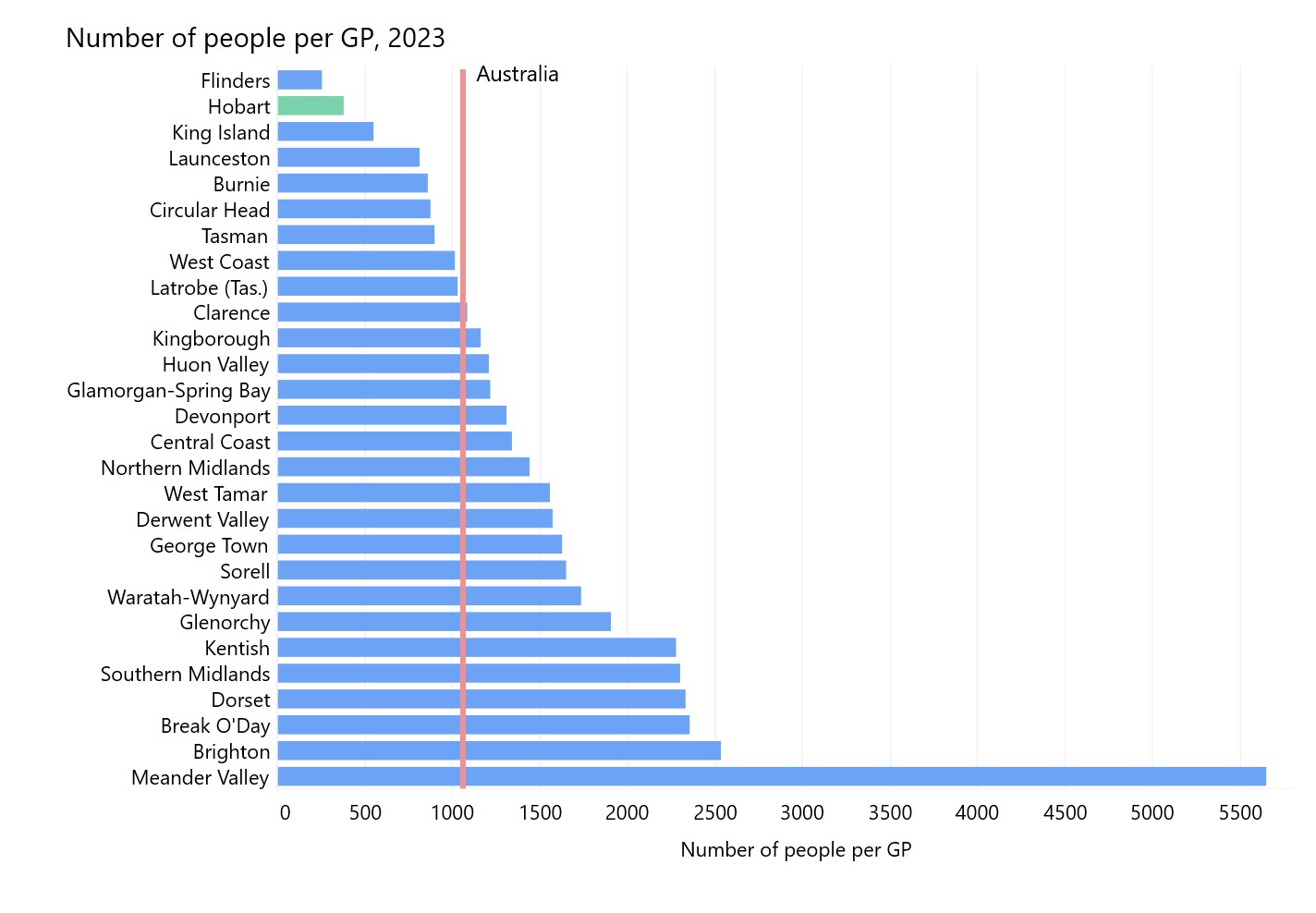

Supply is also a big challenge in Tasmania. In 2023, the national average was one full time equivalent (FTE) GP for every 1,059 people. But the number of people per GP was higher than this in 20 of Tasmania’s 29 local government areas (LGAs). The situation is typically worse in rural and regional communities. For example, the number of people per GP is double the national average in LGAs such as Kentish and Southern Midlands. In Meander Valley, it’s five times more than the national average – there’s one FTE GP for every 5,644 people – although this might be mitigated by residents of the suburban areas of Meander Valley accessing GPs in the neighbouring Launceston City LGA.

Primary care and election promises

The

Labor Government's response to Australia’s primary care challenges has been to unveil what it calls the “[l]argest single investment in Medicare since it started.” Beginning this November, bulk-billing incentives will be expanded to cover all – a policy the Coalition supports. Health Minister Mark Butler predicts that nine out of ten GP visits will be bulk-billed by 2030 because of the expanded bulk-billing incentive. Paying an out-of-pocket contribution has been normalised of late and there are

concerns that if indexation of the rebate isn’t built into the new legislation then we will again suffer the impact of a rebate freeze.

On the supply side, both parties have announced measures to tackle the issue of GP shortages – such as salary incentives and training that encourage more doctors to become GPs in under-served areas.

Labor has promised to add 400 new GP training places per year, so that by2028, more than 2,000 doctors a year will be commencing training in general practice. The

Coalition has outlined a workforce strategy that includes 200 additional new commencing medical school places, specifically focused in regional, rural, and remote areas.

The

Australian Medical Association has welcomed the policy announcements from both sides of politics, acknowledging that they will help address affordability issues for some who don’t currently qualify for bulk-billing. Likewise, the

Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) has welcomed the initiatives but also warns that the announcements won’t mean that everyone will be bulk-billed because the patient rebates will still be too low to cover the true cost of care.

Government modelling has sought to head off such concern, suggesting that universal bulk-billing clinics could become more profitable than mixed-billing clinics that provide the same number of services. However, there are

concerns that the modelling assumes that GPs see more patients than is achievable.

Specifically for Tasmania, Labor has committed to 20 new medical student places each year in Launceston – and for the first time, students will be able to do their full degree in Launceston from start to finish. This matters because doctors often end up working where they train. As

Dr Toby Gardner, Chair of RACGP Tasmania and UTAS Lecturer, puts it: “More medical students studying and graduating in Launceston means more doctors living and working in Launceston, so the entire community will benefit”.

While these are all positive steps, there are other policy measures that could address GP shortfalls that are not on the policy radar from either side. There have been

growing calls for systemic change that supports a variety of health care professionals to operate at their full scope of practice and team health care. In this respect, we’re

behind the rest of the world. In England, there’s one supporting clinician for every three GPs. In the US, nurse practitioners and physician assistants deliver approximately 11% of non-hospital medical care. In Australia? Less than 0.1%.

Fast medicine isn't always better medicine

While there is a consensus that the extra money is welcome, many argue the reforms still leave major systemic issues unresolved. Hobart GP Dr Emma Shoemaker says that

her practice won’t be signing up to the new bulk-billing incentive because in order to make it work, “you’d have to move through patients a lot quicker”. Her concerns are echoed across the profession. An

ABC News survey of more than 800 GPs found that two-thirds don’t plan to increase their bulk-billing, claiming that the policy encourages shorter appointments and could “compromise quality care”.

It’s true that the

new Medicare changes incentivise short GP visits over long visits. Short consultations will be reimbursed at about $11 per minute in inner city areas and over $14 in rural areas, while longer consults will only attract a $4 reimbursement per minute. This model undermines care for patients with complex needs, such as those with chronic conditions, mental health issues and those who live in rural and regional areas (who typically require more time with their doctor) – all of which are over-represented in Tasmania.

It also particularly affects female GPs and their patients. Not only do patients with complex needs often seek female GPs, on average female GPs spend more time with their patients compared with male GPs, and report handling a higher share of mental health consultations. Some

female GPs report charging for shorter consultations even when sessions run long, simply to reduce the patient’s out-of-pocket cost. Yet, the new Medicare changes will continue to penalise this sort of slower, more comprehensive care.

Introducing: Urgent care clinics

The new Medicare Urgent Care Clinics (UCCs) have also been at the forefront of discussion about GP access. UCCs were launched by the Australian Government in 2023 to alleviate pressure on hospital emergency departments (EDs) by offering bulk-billed, walk-in and episodic care for urgent but non-life-threatening health issues. There are currently UCCs in Bridgewater, Launceston, and Devonport, as well as two in Hobart – with

promises of three new clinics coming to Burnie, Kingston, and Sorell.

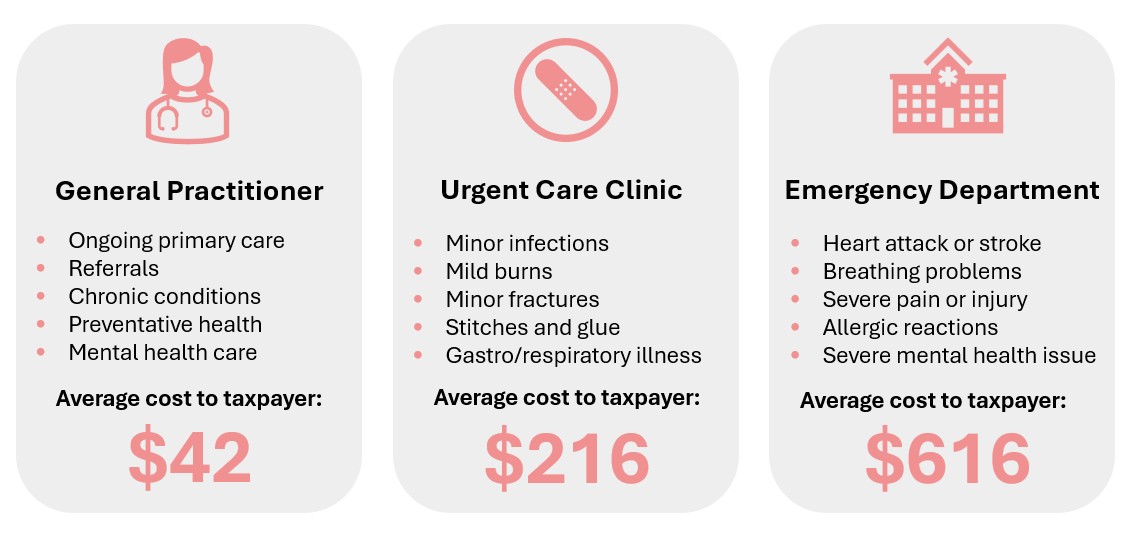

UCCs are proving popular: between June 2023 and December 2024,

they received 1 million visits. And while it’s still early days,

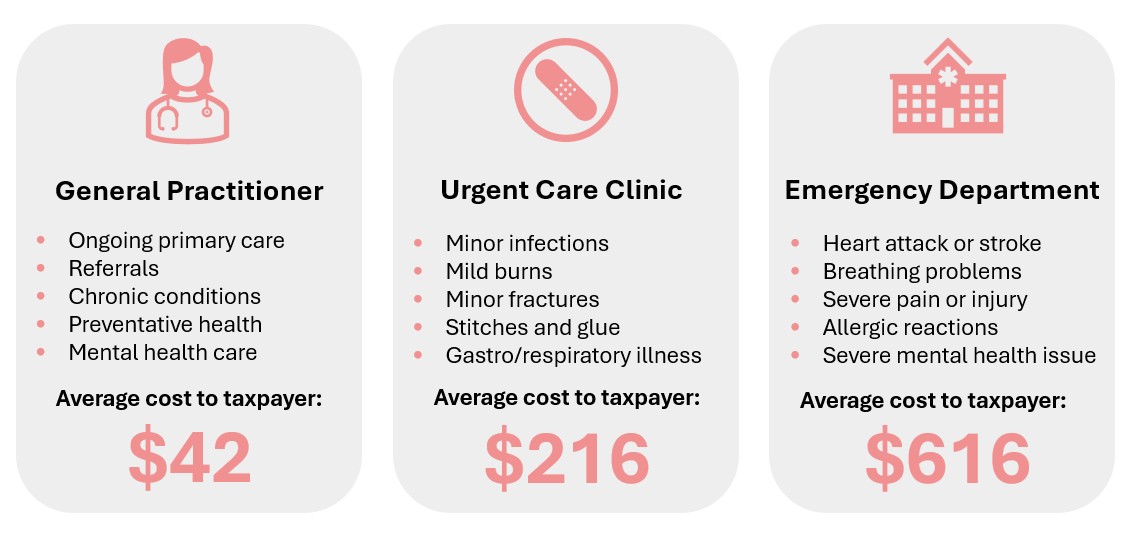

an interim evaluation of the UCC model found that patients appreciated avoiding extended waits in ED and having access to bulk-billed care. UCCs also seem to be saving the taxpayer money: the evaluation estimated that a UCC visit costs $216, whereas an ED visit costs $616. According to the evaluation, 46% of UCC patients reported that they would have otherwise gone to an ED – therefore saving the public purse a considerable amount. However, it’s worth noting that a UCC appointment still costs $174 more than the standard current GP rebate ($42).

What the interim evaluation doesn’t spell out is that EDs and Medicare services are funded by different levels of government – states largely cover EDs, while the Federal Government funds Medicare and UCCs. These separate funding “pots” create cost-shifting and add complexity to how services are delivered, a problem that has long been recognised as a barrier to healthcare reform.

AMA Tasmania has suggested that Tasmania could be an ideal place to trial a different approach, proposing a single funder model for healthcare.

UCCs are not a cure-all solution – the RACGP warns they can disrupt continuity of care between patient and regular GPs, and is concerned about the cost of clinics to taxpayers. However, a

recent national survey of 795 GPs found that three-quarters of GPs who had seen patients who had visited a UCC in the previous month said that UCCs improved timely access to care and reduced pressure on EDs. Additionally, 64% believed that UCCs had a positive impact on their patients’ health outcomes.

The interim evaluation’s bottom line is that while the UCCs are both cost-effective and appreciated, there are also ongoing challenges and ways to refine the model. It highlights workforce challenges to meeting demand, particularly in rural and regional areas – the very same challenges communities already have in accessing GPs. This means that UCCs are competing with general practices for the same workforce.

What's missing: A system built for the future

While Australia has been rightly proud of its healthcare system, with Medicare as its backbone, it was “

designed for an earlier era”. The reforms promised during the election campaign, together with previous initiatives such as UCCs, might help ease some pressures, especially for those patients who will be able to access more affordable care. Ultimately, though, Tassie’s healthcare challenges won’t be solved by incentives for bulk-billing and short-term initiatives alone. Without bigger structural changes, Australia’s health system will remain fragile. Fortunately, there are some great ideas out there for how things could change.

The

Grattan Institute, the

Strengthening Medicare Taskforce Report, the

Scope of Practice Review, and the

AMA are some of those who propose systemic reform. Recommendations include indexing Medicare rebates to adequately reflect the ongoing cost of healthcare and a new and more coherent funding system that supports:

- Employment of other clinicians, such as nurses and physiotherapists, in GP practices

- Team care and increased collaboration (including GPs, nurses, and other providers)

- GPs to spend more time on complex cases - for example, by combining appointment fees with a flexible budget for each patient based on their level of need; and

- Integration of local health systems and person-centred care to link together hospitals, general practices, pharmacies and other partners;

If we aspire to provide quality primary health care to all Australians regardless of where they live, we will need to go beyond policy-by-election promise and commit to a proper, systemic overhaul of our approach to primary healthcare.